In a recent response to a David Brooks column, Rod Dreher wrote that “People today feel liberated from any obligation to place, and all that entails (family networks, especially). Rising to the potential of one’s merits is not only one thing they think about when deciding on a place to live; it’s the only thing.”

We’re all well aware of the positives that come from this sort of social arrangement. It turns out that when you put millions of highly-talented people into one small urban area, they can generate huge amounts of money as well as other types of wealth. That’s no small point, especially when that wealth is put to good use. That’s one of the many reasons, I suspect, that the “metro-evangelicals” (led by thinkers like Tim Keller and Andy Crouch) have become so prominent in recent years.

And yet we’d be remiss if we didn’t also consider the potential problems when place and family weigh so lightly on the minds of talented young people. One way to highlight the dark side to geographic meritocracy is to simply read a book like Hollowing Out the Middle. Reading such a book shows us what our abandoning of small places for larger ones has done to those small places—and why that matters for everyone. But ultimately that kind of argument for place turns largely on appealing to rationality and empathy. These are two powerful faculties to appeal to, but ones that are incomplete and can go badly wrong.

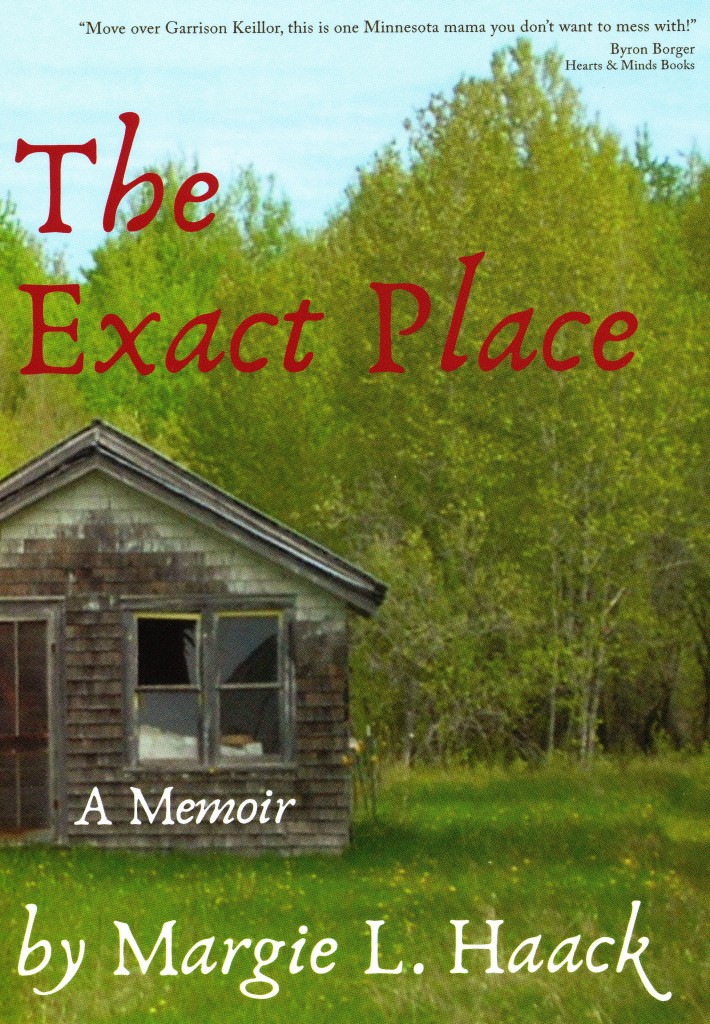

A stronger appeal can be made on the level of desire, by showing what it is to belong to a small place and, even with all its difficulties and pains, come to love it. Done rightly, that sort of appeal shows contemporary readers what precisely we’re losing when we abandon small places to focus all our attention on the life of a few large urban hubs. And that brings me to Margie Haack’s exquisite memoir The Exact Place. (Full disclosure: Margie is a close personal friend.)

The Exact Place is Margie’s memoir of growing up in Warroad, Minnesota—a small town that is quite literally a stone’s throw away from the border. Margie grew up on a small family farm, with a step dad who never came to love her, a mother who cared for her but had many other obligations and responsibilities, and five half-siblings looking up to her. (Margie’s father died in a plane crash while Margie’s mother, 17-years-old at the time, was pregnant with her. When Margie was still very little, her mother remarried.) In many ways, The Exact Place is an unlikely story to evoke wistfulness or nostalgia for small places. It is, at times, a very painful read. Margie tells the story of how she repeatedly tried to win the affection of her step-father but never quite could, even though she would try to convince herself that she had. In one of the more devastating scenes, Margie tells the story of how on the drive home from visiting her parents, her children asked her why grandpa was nicer to the other grandkids. Margie tried to explain it away, saying that was just his way, that he really loved them all the same, and so forth. But then Denis, her husband, quietly said, “No. He pushes our children away and allows all their cousins to sit on his lap.”

Margie also describes some of the typical fears and inadequacies you’d expect to find in a bookish teenaged girl growing up in a poor family in rural America. Her love of books wasn’t always understood, she wasn’t always popular with the other kids at school, and her parents’ strict religious beliefs made things even harder for her. And yet Margie looks back on those years now with a fondness and a recognition. The book’s title comes from one of the last pages in which Margie says, at the end of her story, that she now sees that she was in the exact place she needed to be as a child.

The story is important for two reasons (well, perhaps three… Margie includes some wonderful family recipes for a variety of dishes at the end of each chapter). First, because it is marked by the gratitude and wisdom that we can only wish marked all Christian memoirs. One of the most challenging things to me about Margie’s story is the lack of bitterness in her writing. You never get the sense that she turns against her step-father despite all his cutting remarks and lack of affection for her. There’s a generosity in her spirit that is exemplary and that we all can learn a great deal from.

Second, we need this book because it is a sympathetic story of life in smalltown America. Note that I don’t call it a romanticization. There are, of course, fun stories of the farm–like the time Margie and her siblings let their horse in the house, the horse took a bite out of the radio, and Margie and her siblings invented a story (that their parents miraculously bought) to explain the bite-shaped chunk taken out of the radio. But this isn’t a sentimental story that depicts farm life or rural America in unrealistic terms. Margie is unflinching in her portrayals of its darker sides, including one especially harrowing scene in which a neighbor who seemed to be a pedophile of some sort got into the house with Margie and her siblings while their parents were away.

What Margie does so masterfully is she paints a picture of a place that we can love and feel affectionate toward while still being aware of its many darknesses and shortcomings. It’s a stark contrast to the way so many of my peers, and I include myself in this number, sometimes speak of our home places. Margie’s story, if nothing else, is a reminder to us that there is more to life than professional success and chasing it from distant city to distant city. There is love and fidelity for a place, even places that can at times be quite dark.