If I say to you that no one has time to finish, that the longest human life leaves a man, in any branch of learning, a beginner, I shall seem to you to be saying something quite academic and theoretical. You would be surprised if you knew how soon one begins to feel the shortness of the tether, of how many things, even in middle life, we have to say “No time for that,” “Too late now,” and “Not for me.” -C.S. Lewis, Learning in Wartime

My father is a wise man. It was with his typical wisdom that he once reproached me, his firstborn, for complaining that I was bored: “Justin, the universe has no obligation to entertain you at every moment of your existence.” That was the last time I ever complained of boredom around him. I fully expect one day to turn to my child, upon his discovery of boredom, and utter those same words. Boredom and waiting for Christmas – these are the two earliest existential interactions with time that children have, and they both stem from the same source. Both boredom and the excited, sometimes tantalizing anticipation of a holiday that is yet to come stem from a single desire, namely, that the present moment cease to be the present moment. Yet while we may grow weary of the child who cannot simply be content with the time that he currently occupies, his instinct reveals an important insight into the world: all moments are not identical. Time is sacramental because God’s imprint is seen upon it.

The Greek view of the cyclicality of history is pregnant with the possibility of despair precisely because it rejects the unique significance of individual moments. All moments repeat themselves in a literal instantiation of déjà vu, without guidance or direction: “there is nothing new under the sun.” Against this view, Judaism, permissive of and expecting divine intrusions into our human realm “under the sun,” saw time as progressing steadily toward “the appointed time,” the kairos. This notion received its fullest expression in the New Testament; Christ begins his ministry in Galilee by proclaiming, “the time (kairos) is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel” (Mark 1:15).

N.T. Wright argues in his recent book, Simply Jesus, that Jesus harnessed the Jewish conception of time and applied it to himself. The appointed time has arrived and time, like our very souls, has been redeemed. The main doctrine of Jonathan Edwards’ History of the Work of Redemption is that “The work of redemption is a work that God carries on from the fall of man to the end of the world.” Redemption is necessarily historical, so much so that history cannot be jettisoned without grave damage to the Christian system.

Christ’s fulfillment of the kairos redeems all human time. His coming within history to redeem that history begins to roll back sin’s curse upon time, the monotony of interminably cascading seconds culminating in death. Thus Christianity maintains that history is not, as someone once said, simply “one damn thing after another,” but rather, is one of the channels through which salvation is accomplished in the world. To be bored during those moments when the plan of God gloriously unfolds is to be blind to the redemption transpiring before our eyes.

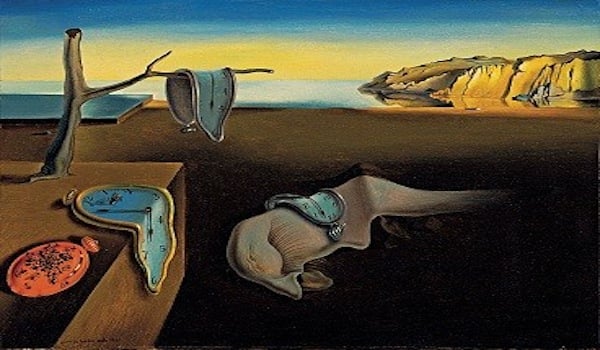

[Image of Dali painting from Wikipedia]