In the summer issue of Fare Forward, due out shortly, my essay on “Cancer and Divine Transcendence” will examine some ways Christians have responded to suffering, and argue that our popular conceptions of providence oft go awry when we overlook the real distinction between God the First Cause and his created second causes. Discussing those who mistakenly speak about tragic events as if their badness were merely illusory, I’ll explain,

Overlooking divine transcendence and collapsing God down into just another actor on the cosmic stage, this misreading of creation’s relation to God poisons our Christian understanding of most everything else as well. When the Creator is made out to be simply the mightiest of creatures, something has gone rotten in the kingdom of theology.

Contra this theistic personalism, the orthodox understanding of God involves a far more robust account of his otherness. On the traditional telling, God is not the most powerful being in the cosmos; he is the very ground of being upon which the cosmos itself rests.

St. Thomas Aquinas draws out this doctrine by elucidating the difference between the First Cause of all that is, and the second causes that this First Cause causes to be: his creation. For Thomas, God the Prima Causa is not a competing cause with his created colleagues, but is cause in a fundamentally different sense. His causal power operates on a different level entirely, acting in part as the cause of our own causal efficacy.

In the course of the article, I also hint that our amnesia regarding transcendence has negatively impacted other areas of theology as well. In these present reflections, I would like to supplement my original essay by diving into some of these many questions, whose solutions have been obscured by the denial of divine transcendence as St. Thomas and the tradition writ large have articulated it.

Perhaps the poster child for this theistic personalism is Notre Dame’s Alvin Plantinga. Whatever the virtues of his philosophizing, and they are plenty, Plantinga’s thought is often premised on a false view of creation’s relation to God. His “free will defense” against the problem of evil, for example, sets up the total activity of God’s will as incompatible with the total activity of man’s own. If God causes something, then man doesn’t, and vice versa. Likewise, his discounting of St. Thomas’ cosmological arguments mistakes creative causation for natural causation. Much of Plantinga’s corpus amounts to simply following the denial of transcendence to its logical conclusions.

A similar point could be made with regards to the doctrine of creation. Pseudo-philosophers like Stephen Hawking and Lawrence Krauss have denied God’s creation of the world because, they claim, scientific data proves the universe did not have a creator. But science proves no such thing, and both theists like Oxford’s William Carroll and atheists like Columbia’s David Albert alike have been quick to point out their philosophical fallacies. Such popular denials of creation are premised on a false dichotomy between creation ex nihilo on the one hand and cosmic autonomy or eternality on the other. They think, in other words, that if the universal is eternal, it does not need a creator. Even Krauss, who thinks that the universe has a beginning of sorts but that its spontaneous coming-to-be requires no extrinsic cause, ascribes to a sort of eternality theory. The virtual fields he posits as necessary for the temporal origin of the material world must have preexisted matter and must themselves have no origin.

Yet again ignoring transcendence, these pop-atheistic writers straw-man Christian thought here, forgetting that St. Thomas defends Aristotle’s belief that, as far as natural knowledge goes, the eternality of the universe is perfectly possible. But for Thomas, as for the mainline of Christian tradition, an eternal universe would still be a created universe. Even second causes that go all the way back temporally would still depend upon the First Cause ontologically. As transcendence instructs, the one has nothing to do with the other, and God’s creative act is necessary for the existence of anything other than himself whether the universe had a temporal beginning or not.

Ethics has likewise suffered from the neglect of divine transcendence. The twentieth century in particular saw a remarkable resurgence of so-called divine command theories, which in effect follow the might-makes-right philosophy of Thrasymachus in Plato’s Republic. These theories pin the moral authority on God merely in virtue of the greatness of his power relative to that of created things: we should obey God because he’s more powerful than us. This again reduces God to just another player in our own causal realm, blaspheming against his transcendence even while reserving for him the highest rung of the created hierarchical ladder.

But perhaps the area of Christian thought most adversely affected by this flattening of the divine has been that of vocation. These days, literature on discernment of spirits abounds, and most every devout adolescent today spends some time—sometimes many years—in a process of figuring out the specific plan God has drafted for his life. While questions of vocation have their proper place in the Christian life, the popular (mis)conception of this inquiry today owes its origin to this same transcendence confusion. “If I do with my life what I choose without an explicit sanction from above, no matter how noble the path is in itself, then I am sinning against God by picking myself over him,” or so the popular modern narrative would lead us to believe.

But on the orthodox account, it is not so. For if human will is not the opponent of divine will, but is efficacious precisely because divine will wills that it be so, then the self-directed selection of one’s state in life or one’s job or one’s spouse is no more inherently wicked than the self-directed selection of one’s breakfast cereal. God may well act so as to miraculously and thus supernaturally reveal someone’s vocation to him ahead of time. But we ought not to go to prayer with the presumption that we will be recipients of such extraordinary advanced copies of our scripts, or simply for the sake of being there to sign for them when the heavenly courier service inevitably arrives. Nor should we fear that acting decisively without such revelations is necessarily an act of culpable egoism. Transcendence saves us from this navel-gazing obsession with divinely revealed foreknowledge and opens us to the one thing necessary, for which we actually ought to go to prayer: God himself.

Ridding Christianity of popular theology seems neither possible nor, frankly, desirable. What we need is a popular theology that is consonant with the truth, as it has been articulated throughout the development of the Christian tradition. In the case of transcendence, the overcoming of our present confusions requires a rediscovery of St. Thomas’ comments in the Summa Contra Gentiles: “The same effect is not attributed to a natural cause and to divine power in such a way that it is partly done by God, and partly by the natural agent; rather, it is wholly done by both, according to a different way, just as the same effect is wholly attributed to the instrument and also wholly to the principal agent.”

And if you want to know what all of that has to do, in a very practical sense, with cancer, then it’s high time you get yourself a subscription.

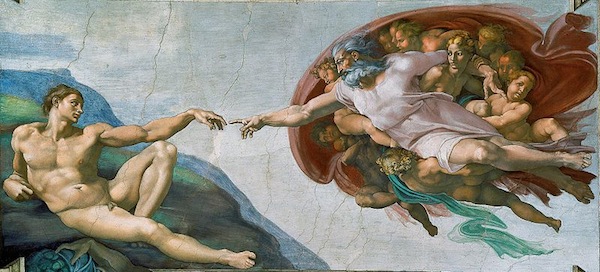

[Image of the Creation of Adam from Wikipedia]