A poignant article rippled through my social media sphere three weeks ago. In “The Art of Presence,” David Brooks describes a family’s lessons on how to support those who grieve or, as he says, “how those of us outside the zone of trauma might better communicate with those inside the zone.” Brooks calls for “a sort of passive activism. We have a tendency, especially in an achievement-oriented culture, to want to solve problems and repair brokenness … But what seems to be needed here is the art of presence — to perform tasks without trying to control or alter the elemental situation.”

In short, Brooks commends faithful companionship to the grieving and condemns shallow platitudes and quick-fix meddling, framing his version of this refrain with the weighty voices of traumatized parents. The public response which briefly pinned his link to my every wall, page, and feed spoke a cry of common agreement, a universal reminiscence of “I’ve been there and have ached for such presence too.” Brooks, however, is hardly the first to articulate this counsel, which echoes works as recent as Rabbi Kueshner’s When Good Things Happen to Bad People (1981) and as ancient as the biblical book Job. But if these sentiments have pervaded human experience, why do we share wounds from moments devoid of their expression? Furthermore, why have I caused some of these wounds?

To borrow C.S. Lewis’s turn of phrase, perhaps everyone thinks faithful companionship is a lovely idea until he is the companion. Brooks may claim that our “achievement-oriented culture” is to blame, but I would argue that the culprit is found closer to home. To enter into another’s zone of trauma requires me to leave my own. To be present in another’s grief asks me to leave mine at the door, to recognize that whether it’s the smallest circumstantial inconvenience or the largest personal bereavement, it is in this moment secondary to the grief of the one I’m facing. Yet the Apostle Paul’s seemingly obvious urge to “Rejoice with those who rejoice and mourn with those who mourn” often becomes clouded by my internal defense of “Why can’t they stop thinking of themselves for a moment and talk about my life?” I am too civilized perhaps to admit such impatience in the face of great loss (e.g., death), but is not the same spirit demonstrated in my hasty attempts at comfort? My trite offerings of “God works all things together for good” or “You’ll be so much stronger for going through this” convey little more than, “Please figure this out quickly so we can move on to other things, preferably those that involve me.” Brooks rightly acknowledges that such placations circumvent the grieving process and isolate those in pain from the comfort we can provide – simple shared presence in day-to-day life. I certainly have no hope to provide answers or purpose for sorrow. Such objects are mysteries hidden in God’s will, revealed in his timing, sometimes only in Heaven.

But I have no farther to look than Christ for what it means to lay aside my agenda in another’s grief and provide comfort. He is the perfect companion, and he knows what kind of faithful presence our grief needs.

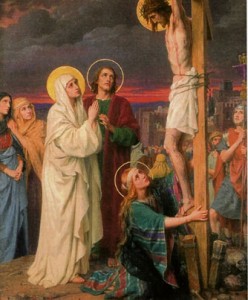

Standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son!” Then he said to the disciple,”Behold, your mother!” And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home. (John 19:25-27)

Here, in the midst of the greatest suffering of all eternity, Jesus turns in compassion to the grief of his beloved mother and disciple John. The simple act of seeing them during his torturous death is astounding, for human grief is often blind. Equally wondrous is his action. Laboring through his last breaths, Jesus does not offer Mary and John the consolation that he will return in three days. He does not remind them that he has repeatedly predicted his death over the last three years of ministry. He does not tell them to seek revenge on the Pharisees nor reassure them that their present sorrow precedes the accomplishment of their eternal salvation. Jesus’s act of compassion at the hour of his death is to unite Mary and John, to offer them shared presence in their grief and to provide them with significance, both deep and mundane (as family is), to another. Christ invites them to relationship with each other as he is in the act of inviting all mankind to relationship with God. In the midst of God’s deepest grief, he reaches out to comfort what Mary and John will soon discover to be but a momentary loss and an eternal joy, and he comforts them through the gift of committed relationship. Brook’s article tugs on my heart as he deftly voices the acute human need for companionship in our grief. But the demonstration of Jesus’ compassion for Mary and John in his death transforms my impatient understanding of grief and the art of faithful presence.