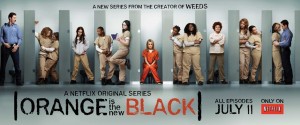

In its first season, Orange is the New Black (OITNB) was a show about a motley crew of women prisoners premised on the fact that these women were much more than criminals. They were mothers, wisecracks, lovers, entrepreneurs, dreamers and, most of all, friends (albeit among racial lines). It was also, on the other hand, a show about how there are “criminal” desires in all of us, even in bourgeois, educated people like Piper, the protagonist in the first season, who finds herself maliciously destroying a fellow inmate in the first season’s finale. By and large, the theme of ONTB’s first season was that if you want to survive in prison – and perhaps in life – you had to have friends and allies. No matter how strong you were, if you were an island, you were screwed. You certainly had to be tough, savvy and street-smart, but you had to have human values such as loyalty, empathy, and fairness because those were the only ways to forge relationships—this was the formula to survival. You had to have humanity; you had to be more than just a stereotypical criminal.

The second season pushes that formula to the test. What if the answer to surviving and thriving is actually to be Machiavellian, to manipulate people by tapping into their base desires so that they are forced to be loyal to you? What if prison is simply a pressure-cooker that simply brings out the worst in others? It poses this question through Vee, a truly Machiavellian woman who, when on the streets, was a mother-figure to foster kids, raised them, and got them to deal drugs for her (and secretly killed them if they turned on her). She does something similar in prison: She finds a way to smuggle in cigarettes and heroin, convinces her fellow black women to help her, and rises to the top by milking people’s addictions for stamps (and kicks one of her own as soon as she poses a risk to her business).

With the introduction of Vee, the prison slowly descends into a dog-eat-dog world. Power plays and betrayal (even within racial groups) are rife. The question “what’s in it for me?” becomes more and more popular. Red, a woman whose business route is threatened by Vee, attempts in one of the final episodes to kill Vee, but stops herself at the last moment and wonders aloud to Vee, “How did I get to the point where I am trying to kill you so that I can sell mascara in jail?” Most tellingly, when someone calls out the black women for selling heroin to recovering addicts, they essentially respond by saying, in perfect antithesis to the spirit of Season One, “Last time we checked, we are all criminals. Who are you to take the moral high ground?”

As the second season spirals out, not only is the show devoid of hope, but it openly mocks standard carriers of hope. Soso, a recent, idealistic graduate who was most likely imprisoned for participating in protests, tries to stage a hunger strike against prison conditions and is, for the most part, jeered at for her naïve ideals (she is, ironically, on the same plane as Vee; both are alone and friendless, despite their opposite intentions). The show takes a swipe at Democrats, satirizing restorative programs such as “Dress for Success” and the false hope they promise, and is brutally critical of the means by which politicians, especially Democrats, employ a “means justify ends” logic by stepping on the lowly in order to gain the political power to uplift those upon which they have just trodden. It is also takes a cynical view of institutional justice: the drug lord whom Alex risks her life to testify against ends up walking free, and the federal investigators of Red’s violent beating are hastily un-thorough in their detective-work because one of them wants to get home in time for a date with his wife. Right up until the season finale, it seemed likely that Machiavellian logic – there is no real justice or hope, so your only option is to look out for yourself – was going to prevail.

What does any of this have to do with Shakespeare? Most of Shakespeare’s plays contain an underlying worldview that there is a natural hierarchy of being that, when threatened, will break out into unnatural chaos and eventually re-right itself. When Macbeth, for instance, a lord, commits regicide, an act that upsets the natural order in which the king is supposed to be above his lords and servants, not only is his internal order disrupted (he is haunted by literal ghosts and personal guilt), but nature’s order starts turning topsy-turvy. A falcon is killed by an owl that usually hunts mice; the king’s horses “turn’d wild in their nature,” broke out of their stalls to “make / War with mankind”; witches arise to proclaim Macbeth’s death, fated for when a forest begins to march against him. Eventually, the witches’ fated proclamation is proved true: Macbeth, after ruling for a number of years as king, is killed in battle.

Just as our bodies try to cough up foreign objects we are not meant to swallow, Macbeth, through his unnatural act, becomes the foreign object which Shakespeare’s world must inevitably expel. In OITNB, Vee is the foreign object that represents an alien logic and introduces disruptive chaos whom the prison, which is bound together by lines of loyalty, must eject. In the season finale, her sociopathic lack of loyalty is finally realized by every single person and, suddenly, everyone turns on her, even bystanders who have little to do with Vee but understand that she might harm them next. For once, all racial groups are working towards a single goal: the Latinas are working with the white girls to poison Vee, the black girls have banded together to turn Vee into the authorities, and Red’s friends are trying to expose Vee’s heroin trade.

The symbolism of the ejection is concretely manifested when Vee, understanding that she is exposed without allies and thus has no power, ejects herself from the prison by climbing out of the sewers. She is then killed in a fairly absurd manner; Rosa, a prisoner with terminal cancer (and perhaps the character with the least hope), runs her over while driving a van. It is an absurd death, in light of all the other more plausible ways she could have died, but it simply reinforces the fated nature of Vee’s end: no matter where she runs, Birnam Wood will move against her. Machiavelli loses; humanity – beaten-down, bones-crushed, wised-up, but still alive – wins. If the question of Season One was “What does being a criminal mean?” the question of Season Two was, “Where is hope found?” Not in the form of an external savior, but in the collective, human strength of all the prisoners who simply declared through their actions: Not in our house.