PTC: Just so you know, I write for both the UBC student paper and a Christian paper as well, so I’m something of a journalistic double agent.

PTC: Just so you know, I write for both the UBC student paper and a Christian paper as well, so I’m something of a journalistic double agent.

MS: Oh good! The more the merrier!

PTC: I saw you perform at Greenbelt in 1994. How did you find the experience?

MS: I enjoyed it. I played there because I know a guy named Martin Wroe, he’s one of the organizers. He and I are both lovers of the island Iona, and so he asked me to play and I said, “Okay.”

PTC: In last week’s Georgia Straight, it said that you liked all the religions but especially the Eastern ones. That struck me as odd, since Christianity and paganism, the two religions that figure prominently in your lyrics, are both Western ones.

MS: I don’t especially like Eastern religions. I suppose I’m more rooted in the culture that I’ve grown up in, Western culture. But I have got a lot of benefits from my small learnings in Eastern religions. I’ve learned to meditate, when I was in New York, from the Indian tradition, and that was really great and I got a lot from that. I haven’t looked deeply into it, I haven’t studied Hindu scriptures or anything like that, I just learned to meditate simple as that, but it gave me a lot. I don’t belong to any religion, I wouldn’t even call myself a religious person, but I do believe that life has a purpose and I believe there is a power of love behind the whole universe, and I think that power is in me and you and everyone in the universe as well.

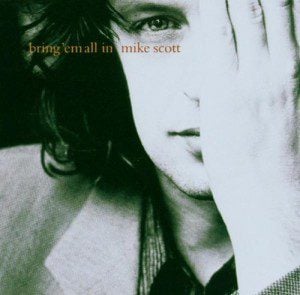

PTC: You spent a year and a half in the Findhorn community, and it figures prominently on Bring ’Em All In. How would you describe Findhorn?

MS: It’s a spiritual community. It’s an ecological community as well. The premise in the Findhorn community is pretty much what I just said myself, that life has a purpose and there is a divinity in all creation. At Findhorn there are people who belong to different faiths, or no faiths, working and learning together, and it’s a hard place to sum up. I guess if I had to sum up I would say it’s based on what’s called the perennial philosophy, which is the philosophy that is held to be behind the majority of world religions, which is what I’ve said twice already, that life has a purpose and so on. I see you have a book about Gnostic something-or-other, and the Gnostics believed, I think, in the perennial philosophy too.

PTC: I saw a copy of a Sunday Mail article that referred to Findhorn as a “cult”. How do you respond to that?

MS: It’s absolute fantasy. You probably don’t know the Sunday Mail here in Canada. The Sunday Mail is the equivalent of the National Enquirer in Scotland. The guy who wrote that, he actually came and looked me up in Findhorn, and he was very threatening and offensive and used fear as his main prodding stick to get anything contentious out of me — which he didn’t do, he didn’t get any contentious word out of my mouth — so it’s a lot of complete rubbish. And no one who’s been to the Findhorn community in a million years would describe it as a cult. A cult to me is something where there’s a strong dogma, a fringe dogma that has to be rigidly adhered to, particularly with a very strong personality in charge of it who reaps all the benefits. I wouldn’t be involved in something like that in a thousand million lifetimes.

PTC: Ah. Well, that word did make into headline, so I thought I’d ask.

MS: “Cult Saves Rock Star From Drinks Hell.” I remember it well.

PTC: Your music seems very personal on this solo album. Will it continue to be this personal?

MS: It will probably swing another way on the next record. This was a particular album for a particular period of time. I really love this album, and I love that the songs are so autobiographical and some are diary-like and they are very specific — place names, events, and so on — but I don’t think I could keep doing that. I think that’s this album, and the next album will be quite different.

PTC: With lyrics so personal, do you sometimes think that working in a band is really nothing more than a solo performance with just extra musicians backing you up?

MS: Well, if I put together a band in the future, that’s the way it would be, I think, because I would continue to work under my own name. But that’s not the way it was in the Waterboys. Sure, it was definitely my own band, I was the leader and I was the main creative driving force, for sure. But the other members — especially in the period when we were based in Ireland from ’86 to ’90 — in that period, the other members brought a lot and they had quite a strong influence on the sound and on the kind of material we played, and it took us into Irish music and Celtic music, and then [Anthony Thistlethwaite] the sax player, he brought in a large range of influences himself.

PTC: Would you say, then, that Dream Harder was a solo album posing as a band album?

MS: Yeah, I wanted to put together a new band in New York that would be a new Waterboys. I hadn’t even thought of going out solo, I was just comfortable with the Waterboys identity. I always liked bands. So I tried to put a new band together and I made the album under that premise, but once I made the album I didn’t feel they were the right musicians to tour with. I tried to find more musicians, I did a lot of auditions in New York, and at the end of that it’s like a lightbulb went off above my head and said, “This is not happening, this is not what’s meant to happen. Take another course.”

PTC: Do you ever worry that —

MS: I never worry.

PTC: Okay, does it ever concern you that songs like ‘A Man in Love’ and especially ‘I’m Learning to Love Him’, with their punchlines pointing back at you, might be perceived as artistic narcissism?

MS: Well, I know that I’m not narcissistic at all, so I feel that when people make comments like that — I haven’t heard many comments like that, I’ve had a few — I kind of think it’s because of their own problems. I think if someone is uncomfortable with being intimate with themselves, they might find some of those songs uncomfortable to listen to. I don’t think there’s anything narcissistic about learning to accept myself, which is basically what the song is about. If I can’t love and accept myself unconditionally, then how can I love and accept other people? And that’s been a very important thing for me.

Through a lot of my life I’ve criticized myself. I grew up in Scotland; in Scotland if you do anything out of the ordinary, someone comes along and says, “Who do you think you are?” I’ve grown up with that attitude all my life, and I’ve come to realize in the last few years that I’m not any different from anyone else. I don’t think I’m a more special person than anyone else, but I do think I’m a great person, I’m a great guy, and I’m stuck with myself for the rest of my life, so I might as well get on with myself. And I don’t think that’s narcissistic. Narcissism is a different thing altogether.

And if people can’t tell the difference, it’s their problem, not mine. And it’s probably because they don’t love themselves, and they have a problem with me saying that I can love myself. And loving oneself is a very difficult thing for us humans. It’s something that I think we all have to learn to do.

PTC: You do have a tendency to take serious spiritual issues and, say, put them to a cheeky rhythm — “Hey, ho, skadoodle-i-o, spiritual city, gonna watch it grow” and all that.

MS: Oh sure. God is fun. They say that when we laugh we’re really, truly alive.

PTC: I especially liked the way you went from ‘The Return of Pan’, which is a great song, to the more goofy ‘Corn Circles’.

MS: It’s kind of mischievous, yeah. And Pan is mischievous. I thought that was a really good pairing. It rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. One guy in Britain said, “You had these four real great songs, all good stuff, big numbers, and then you put ‘Corn Circles’ in!” Well, I thought that was very funny! I don’t take myself too seriously.

PTC: You once said you wouldn’t make videos. What’s your stand on that now?

MS: I didn’t for a long time, but I have since 1993, I’ve made four videos. I’ve made my peace with it.

PTC: Do you ever write songs with videos in mind?

MS: No. Never ever ever ever. That feels a bit like getting the cart before the horse, to me.

PTC: Would you say there is some sort of unifying, consistent thread running through all the different styles of music you’ve done?

MS: I don’t know, it’s for you guys to work that out! I suppose the song is always the most important thing, and the musical styles are the suit of clothes that the song wears. I’m always wanting to write a better song than I did before. I’m always working on my songwriting, and that’s the core thing for me, and the style of the music is a secondary focus. I know that the way I write changes all the time, it has its own evolution, and that’s the way it should be.

PTC: It’s been said that the Waterboys were poised to become really successful in the mid-’80s, but then you stepped back from all that. In a recent interview, you said you had settled a number of personal issues and now you were ready to go out and reach for “success.”

MS: Sure. All those other things were important to me. My music, and my health, and love, and learning as a man — they were all more important to me than success. So at various times in my life I took turns that would get me what I wanted at the time, which wasn’t always success. I’ve always wanted success, but I haven’t wanted it more than peace of mind. I have such a surfeit of peace of mind now, that I can put my energies into that form of success. Actually, it’s a careless quote, because to me success is being a fulfilled person, being a truly alive human being. That’s success. Success on this material level, in terms of record sales and so on, yeah, that’s success on one level, and that’s the success that I would like now. Do you know what I mean?

PTC: Oh, I think so. One last question: You said a few years ago that you believed in God and you believed in Jesus. What does that mean to you?

MS: I’ve always believed in God. I’ve always believed that there is a God, a creator of the world, the universe, of myself, and the moments in my life when I’ve come close to an understanding of God have always been times when love has been very present. I would agree with that bumper sticker that you see on cars that says, “God is Love.” I would subscribe to that.

And I believe in Jesus too, yeah. I grew up in a Christian culture, and often through my life I’ve felt, “Well what would Jesus do here? What would Jesus think here?” So I suppose in that respect, the figure of Jesus in my imagination is a sort of hero figure. Not the only one, but perhaps the most wonderful one. But at the same time I wouldn’t call myself a Christian, and I don’t think the two statements are contradictory either. I think I can grow up in this culture and have a relationship with a power that is called Jesus without being a card-carrying Christian, and yeah, that’s me. And I have a relationship with a power that’s called Pan, as well.

PTC: That certainly comes across in ‘The Return of Pan’, when you say, “Follow Christ as best you can, Pan is dead, long live Pan.” Is one deity a continuation of the other, then?

MS: I don’t feel that the two are mutually exclusive. You mentioned pagans and Christians earlier. I think we’re all of us humans involved in this grand road from the same light and moving to the same light. And we have different parts. And I think all the different parts are valid, they suit different cultures, they suit different temperaments, different types of people.

PTC: Alright. I think we have to give the photographer a chance now. Thank you very much.

MS: Now I have to ask you a question. Do you think Findhorn sounds like a cult?

PTC: Well, I would agree with much of what you said before, that a cult has its own dogma and so forth, though I don’t think you need a single personality at the top who benefits from it. I think just having peers forcing you to keep in line and conform to the dogma can produce a cult mentality.

MS: Do you know the concept of the still small voice within? Eileen Caddy directed a lot of the early building of the community based on the still small voice within, and she has lots of books on the guidance that she received from this voice, and they’re very close to Christian mysticism, for what it’s worth. You might like it, I don’t know.

— Portions of this interview appeared in an article for The Ubyssey. Click here to download a PDF file of the issue in which it appeared.