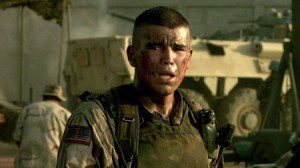

The folks who brought you Pearl Harbor are now bringing you Black Hawk Down, and despite the fact that both war movies feature Josh Hartnett and Tom Sizemore in key military roles, the films are very different.

The folks who brought you Pearl Harbor are now bringing you Black Hawk Down, and despite the fact that both war movies feature Josh Hartnett and Tom Sizemore in key military roles, the films are very different.

Where Pearl Harbor was full of saccharine romance, nostalgic production design and eye-popping special effects, Black Hawk Down is a decidedly grim and realistic account of a botched military operation that resulted in the deaths of 18 Americans and more than 1,000 Somalis eight years ago. Where Pearl Harbor was widely dismissed for its commercialism, Black Hawk Down tries very hard to earn respect. This is the film producer Jerry Bruckheimer hopes will be remembered at Oscar time.

But for all the accolades the film has already received, there isn’t much to Black Hawk Down besides a non-stop barrage of bullets, grenades and rockets, most of which is shot in a style that emphasizes the often random and chaotic nature of warfare. OK, so war is hell — most of us already know that. But what else is the film trying to say? To the extent that the film puts the action into any sort of broader historical context, it is spelled out in an opening-titles sequence which talks about a civil war in Somalia, the 300,000 Somalis who died of famine, the 24 Pakistani peacekeepers who were killed in an ambush by men working for tribal leader Mohammed Farrah Aidid, and the arrival of American troops to sort out the mess. Once the Americans embark on their mission to capture two of Aidid’s top lieutenants, and once the first of their helicopters is shot down, the fighting is all that matters. Their reason for being there is promptly forgotten, and is about as relevant to the film as the opening scenes are to any Jackie Chan stuntfest.

Director Ridley Scott, who proved he has a strong stomach with the gore and violence of Gladiator and Hannibal, throws enough severed limbs and shattered bodies onto the screen to make the audience squirm, and in one scene, his camera gets up close as a soldier performs an emergency operation on another, without painkillers, by plunging his hand deep inside the other soldier’s wound.

But as visceral as the imagery can be, Scott leaves out perhaps the most infamous symbol of this whole affair, namely the sight of one American soldier’s half-naked body being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu. That’s a little like showing the bombing of Pearl Harbor without the sinking of the USS Arizona. Perhaps Scott didn’t want to offend Americans for whom that particular image would be not only too painful, but too shameful. Or perhaps he knew that, to do the scene justice, he would have to get closer to the Somalis themselves, who, with one or two brief exceptions, are mostly reduced to cannon fodder like so many stormtroopers in a Star Wars movie.

For that matter, Scott never gets particularly close to the Americans either. The script, adapted by Ken Nolan from Mark Bowden’s best-selling book, makes only fleeting attempts to develop any of the characters among the Delta units and Ranger infantry who populate this film, and its efforts in this regard are trite and conventional. Ewan McGregor plays a desk jockey being sent into his first battle. He talks a lot about his expertise in making coffee; his fellow Trainspotter Ewen Bremner provides comic relief as a soldier who goes deaf from the gunfire; and The Lord of the Rings’ Orlando Bloom plays a bright-eyed kid who is, of course, one of the first to be injured once the shooting starts. Early on, Hartnett’s character is called an “idealist” who likes the “skinnies,” as the troops call the Somalis, but the film never explores the effects this incident may have had on his politics.

The nearest thing the movie may have to a mouthpiece is a soldier (played by Eric Bana) who comes off as jaded at first, but turns out to be just a guy doing his job. Politics don’t matter when the bullets fly, and no one outside the army will ever understand that those who join the military do so for the camaraderie, he says. As with that character, so with the film. Black Hawk Down is simply another film about guys sticking together in harrowing circumstances, and whether it’s in the skies over Hawaii or in the streets of some African city isn’t all that important.

Those hoping for some insights into the state of the world had best look elsewhere.

2.5 stars (out of 5)

— A version of this review first appeared in the Vancouver Courier.