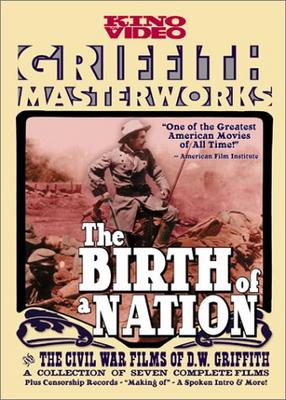

Today I finally plugged a big huge gap in my film journals. Today I watched The Birth of a Nation (1915), one of the first major hits of American cinema, a milestone in the development of cinematic technique, and the centre of a political and cultural controversy that continues to this day.

Today I finally plugged a big huge gap in my film journals. Today I watched The Birth of a Nation (1915), one of the first major hits of American cinema, a milestone in the development of cinematic technique, and the centre of a political and cultural controversy that continues to this day.

In a way, it’s amazing I had never gotten around to this film before. I remember looking at a photo from the production of this film many times when skimming through the entry on ‘Motion Pictures’ in the World Book Encyclopedia, back when I was a lad. I had heard about the film’s racist content and participated in somewhat abstract discussions regarding the question of whether the film ought to be obliterated from our collective memory or shown today for the sake of both cinematic and cultural history. I saw Griffith’s lesser-known Broken Blossoms (1919) in film class years ago, and I have watched Intolerance (1916) several times for its admittedly skimpy depiction of the life of Christ. But despite it all, the epic success that made all those other films possible somehow eluded my attention.

So, today, I finally watched it. I was impressed by how typically “Hollywood” it was — the crude caricatures of race and class and the fusion of historical verisimilitude with sentimental romance would be right at home in any epic made today, especially if it starred Mel Gibson. (I am thinking of The Patriot, but there wasn’t much romance in that one; for that, turn to Braveheart.)

And while I had heard about the film’s racist content, I was still a bit surprised to see how overt and over-the-top it was — and how the film justified this element by quoting the history books written by then-president Woodrow Wilson! (No wonder he gave the film his imprimatur.) I have to say I really don’t know if I would ever want to screen this film at a theatre, even at a venue populated by educated patrons and devoted to the preservation of film history. For sheer visual impact, I always prefer the big screen to the boob tube, especially when the film was made for the larger medium; but at the same time, there is a communal aspect to movie-going that would make watching this film danged awkward. I’m the kind of person who laughs whenever I see something outrageous, even if it is meant to be offensive, but I would be a little worried that such laughter might offend people who are feeling a little more hostile and hot under the collar; that kind of thing. I certainly do not want this film to be erased from our archives — but I guess I’d be content to let people watch it at home, for the most part.

Bottom line: if the Pacific Cinematheque ever screens the film, I’m going. But I wouldn’t force them to show it, either.

Some other things jumped out at me. The film begins with a “plea” for the “art” of the motion picture — which must reflect the controversy leading to the Supreme Court’s declaration around that time that films were not “art” but a mere commodity, and were thus not protected by freedom of expression laws. (The court did not change its position on this point until the 1950s, IIRC.)

This is followed by a title card expressing the hope that war will be “held in abhorrence” as a result of the film — which must reflect the fact that it was produced after World War I had commenced, but two years before America joined in the fight; indeed, I believe Wilson won re-election in 1916, the year after this film came out, partly because he had kept America out of the war.

I was also struck by the way Griffith footnoted his title cards and listed his sources whenever he was about to show a “historical facsimile” of certain true-life political or historical events; he used a similar technique in Intolerance, every time he quoted a passage from the Bible. However, his claim to have based his depiction of, say, African-American legislators on contemporary photographs is called into question by a making-of featurette on the DVD, which shows how Griffith actually based some of the more inflammatory scenes on political cartoons from the Reconstruction era. And one can only wonder who Griffith thought he was kidding when he included a title card saying that his depiction of history was not meant to reflect on any race or group of people “today”, given that his film fomented the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

I also wondered what went through the minds of the people who compiled, arranged and composed the music for this DVD, several decades after the film’s original release. When Griffith depicts black characters in a way that clearly mocks them, the composer is kind of obliged to write music that complements the mockery — and yet doesn’t that make the composer of today complicit in the very racism of the past that, presumably, the composer would abhor? Then again, I also wondered why the composer had chosen Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ for the climactic scene in which the Klansmen ride on horseback to the rescue — was it because this tune is now associated with similarly historically discredited initiatives such as Hitler’s Third Reich or the Vietnam War (the latter via Apocalypse Now; my review)? (And hey, what about the title card that says: “The former enemies of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright.” I hadn’t realized the word “Aryan” would have been so recognizable in the United States a full decade before Hitler wrote Mein Kampf.)

One last oddity: The bonus DVD includes an introductory film clip produced for the film’s 1930 re-release, in which Griffith and Walter Huston discuss Griffith’s reasons for making the film. At one point, Griffith says, “The Klan, at that time, was needed. It served a purpose. Yes, I think it’s true. But as Pontius Pilate said, ‘Truth? … What is … the truth?'” He says those last words very portentously, and it’s almost as though he’s daring us all to be relativists and to accept his film’s paean to the Klan on that basis. Bizarre.