Two months ago, I took advantage of a series at the Pacific Cinematheque and caught most of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s early films for the first time ever. While I had seen The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) several times, I had never before seen Accattone (1961), Mamma Roma (1962), Hawks and Sparrows (1966), Oedipus Rex (1967) or any of his documentaries.

However, one early film that was left out of the series — and it’s a must-see for anyone interested in Jesus films, especially where Pasolini is concerned — was La ricotta (1963), a short film about a movie director (played by Orson Welles) who makes a film about the crucifixion.

However, one early film that was left out of the series — and it’s a must-see for anyone interested in Jesus films, especially where Pasolini is concerned — was La ricotta (1963), a short film about a movie director (played by Orson Welles) who makes a film about the crucifixion.

This short film, which predates Matthew by one year, was originally produced for Ro.Go.Pa.G., an anthology that included works by Jean-Luc Godard, Roberto Rossellini, and the lesser-known Ugo Gregoretti. The full anthology seems to be available on VHS but not on DVD, at least not in this region; however, Criterion included La ricotta last year on their Mamma Roma DVD, and the introductory menu screen claims it has been unavailable as a separate film in its own right “until now”.

I had wondered at first why this particular short film had been included on the DVD; was Criterion cashing in, however obliquely, on the popularity of Jesus films following the success of The Passion of the Christ? However, having seen the film now, I think not; it turns out there is a scene in which the director played by Welles reads passages of Pasolini’s book Mamma Roma to a journalist — so there, at least, we have an obvious tie-in not only to Pasolini’s films in general, but to Mamma Roma in particular.

La ricotta was apparently so controversial that Pasolini was sentenced to several months in prison for contempt of religion, though the charge was ultimately reversed. The film begins with a disclaimer which may or may not predate the court hearings:

It’s not difficult to predict for this story of mine biased, ambiguous and scandalized judgments. In any case, I want to state here and now that however La ricotta is taken, the story of the Passion, which La ricotta indirectly recalls, is for me the greatest event that has ever happened and the books that recount it the most sublime ever written.

This disclaimer is immediately followed by a shot of two guys doing a twist-style dance to a jazzy bit of rock music, in front of a table covered with food. Thus, an irreverent tone is established from the get-go, and it is amplified later on by the use of time-lapse photography, circus music, and various caustic remarks uttered by an offscreen assistant director.

To the crew members carrying the actors on their crosses up the hill, the assistant director barks: “Get a move on with those crosses! You’re like slugs this morning! We ought to have a whip! Run! Come on, run!” To the actors assembled around the cross, in a scene that evokes the static piety of Renaissance paintings, he shouts: “Sonia, remember you’re at Christ’s feet! Stop thinking about your dog!” Or again, to another actress: “What’s with that face? This isn’t the comedie francaise!” Or again, when an extra wanders into a shot: “Get the Negro out of there!” And sprinkled in among these other comments, the assistant director frequently calls the cast and crew “heathens”, “publicans”, “blasphemers” and so on.

To the crew members carrying the actors on their crosses up the hill, the assistant director barks: “Get a move on with those crosses! You’re like slugs this morning! We ought to have a whip! Run! Come on, run!” To the actors assembled around the cross, in a scene that evokes the static piety of Renaissance paintings, he shouts: “Sonia, remember you’re at Christ’s feet! Stop thinking about your dog!” Or again, to another actress: “What’s with that face? This isn’t the comedie francaise!” Or again, when an extra wanders into a shot: “Get the Negro out of there!” And sprinkled in among these other comments, the assistant director frequently calls the cast and crew “heathens”, “publicans”, “blasphemers” and so on.

It kind of makes you wonder what it was like behind the scenes on Pasolini’s own movie about Jesus, doesn’t it? And given Mel Gibson’s reputation for practical jokes, it kind of makes you wonder what it was like on that set, too. Or what it was like on any Jesus-movie set. For that matter, I sometimes wonder what sort of secret humour goes on behind the iconostasis at church, too.

Of course, Pasolini is not mocking the sacred story itself; rather, he is mocking the hypocrisy that can be typical of the filmmaking process. Filmmakers frequently offer their audiences romanticized and idealized notions of what it means to be a human being, but behind the scenes they can often act in extremely dehumanizing ways. The bulk of the film concerns an actor named Stracci (Mario Cipriani), who is playing the “good thief” on the cross, but is taunted and abused behind the scenes by the film’s cast and crew — including the actor who plays Jesus!

This abuse is expressed in several ways. After Stracci has been “nailed” to his cross — sort of the equivalent of being confined within one’s costume or prosthetic make-up — the crew taunts him by holding food and water just barely out of reach of his mouth, and by encouraging one of the bustier actresses to perform a striptease where he can just barely see it. Given the bawdy, hyper-sexual tendency of his later films, I don’t think Pasolini had all that big a problem with the sexuality on set, per se; rather, his ire is directed towards the scorn that these people heap on the actor, who is not of the same social class as the rest of them.

In another scene, Stracci surreptitiously obtains some food — by disguising himself as a female extra! — and hides it for himself. But when he returns to his food, he discovers that a dog, which belongs to the prima donna who plays the Virgin Mary, has been eating it; so he says to the mutt, “Think you’re better than me because you belong to a star?” This scene works on a number of allegorical levels. In a way, it is a reversal of that passage about dogs eating the scraps from Israel’s table; now it is the poor man’s “table”, and the dog is actually a symbol of the privileged group. Stracci also accuses the dog of being a “dirty thief”, but then you realize that he, himself, is a thief of sorts, albeit a “good thief” — kind of like the character he plays in the film-within-a-film!

Later on, the prima donna complains that there won’t be time to film her scene on the day when it was supposed to be filmed if the director goes ahead with a sequence involving the three crosses; so the crosses are taken down, and the actors are left “nailed” to them while the other scene is filmed. (In one funny montage, we see a series of close-ups as the various production assistants take turns relaying the order to “Do the other scene!” — and the last shot shows yet another dog shouting this phrase!)

Officially, the film was intended as a Marxist critique of bourgeois Catholic Italian society, which is portrayed here as being more concerned with pious appearances and filling its own stomach than with the common humanity of the subproletariat. But there may be an element of self-criticism in this film too.

The director played by Welles calls himself a Marxist, reads Pasolini’s poetry aloud, and says the film he is making is inspired by his “intimate, profound, archaic Catholicism” — words that are rather similar to how Pasolini would describe his own involvement in Matthew. But this director is as cut off from the people who work under him as anybody else, and indeed at one point he expresses deep scorn for the “average man”. Does he represent Pasolini himself? Or does he, perhaps, represent the cultural elite who exploit Pasolini’s poetry for the sake of keeping up trendy Marxist appearances?

The director played by Welles calls himself a Marxist, reads Pasolini’s poetry aloud, and says the film he is making is inspired by his “intimate, profound, archaic Catholicism” — words that are rather similar to how Pasolini would describe his own involvement in Matthew. But this director is as cut off from the people who work under him as anybody else, and indeed at one point he expresses deep scorn for the “average man”. Does he represent Pasolini himself? Or does he, perhaps, represent the cultural elite who exploit Pasolini’s poetry for the sake of keeping up trendy Marxist appearances?

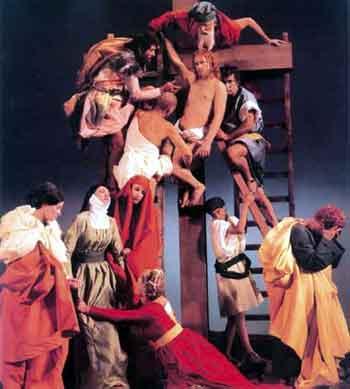

Certainly there are limits to the parallels one can draw between Pasolini and the Welles character. For example, the Welles character appears to be making a film that is absurdly static and full of vivid colour, all for the sake of imitating the classic works of the Renaissance. I don’t think even Hollywood went this far in the sound era, with the exception of a brief flashback to the Last Supper in Quo Vadis? (1951); and Pasolini, despite his occasional nods to classic paintings, went even further in the opposite direction with the active, gritty, black-and-white Matthew.

A couple of final, trivial notes. Hearing some higher-pitched Italian actor’s voice come out of Orson Welles’s mouth is an odd experience. And Rossana Di Rocco, the actress who played the angel in Matthew and a girl dressed as an angel in Hawks and Sparrows, appears briefly here as Stracci’s daughter.