So say the posters for The Da Vinci Code. And so say many Christians who hope to make this movie a witnessing opportunity when it opens May 19 — despite its dismissal of the divinity of Jesus and its controversial claims about the marital status of Christ, the formation of the Bible and the church’s treatment of women.

In contrast to past controversies, such as the various efforts to suppress Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ in the 1980s, pastors and scholars have written books, prepared sermon series, and created websites devoted to “engaging” the movie and book versions of The Da Vinci Code as part of an ongoing “dialogue” with the larger culture.

Those who advocate such an approach say the movie cannot be ignored, because Dan Brown’s novel has already had an enormous impact on the broader culture, and requires an informed and articulate response — a claim that may be confirmed by recent opinion polls.

–

In June 2005, a National Geographic Channel survey found that over 5 million Canadians had read the novel, and of those, roughly one in three believed the book’s historical claims.

More recently, an Ipsos Reid poll released April 16 indicated that one out of six Canadians, presumably including many who have not read the book, believe Jesus faked his death, married and had children — a statistic that many commentators attributed to the influence of The Da Vinci Code, even though it never states that Jesus faked his death.

Darrell Bock, a professor of New Testament studies at Dallas Theological Seminary and the author of one of many books debunking The Da Vinci Code, says it is for reasons like this that the church cannot afford to ignore this movie the way it has ignored others.

“This time, the difference is that, by the time Christians were responding as a group, this book had already penetrated the cultural consciousness, whereas The Last Temptation of Christ never got to that stage,” he says. “It got on the radar screen and people talked about it, but people didn’t embrace it and the ideas it represented.”

Bock adds that Brown’s story has had a major impact due to a paradoxical mix of ignorance and education on the public’s part. On one hand, he says, many people — including Christians — have “a black hole of knowledge” about early church history, “so he was able to say, ‘I carefully researched this,’ and a lot of people were open to that because they didn’t have any context out of which to assess what he was saying.”

On the other hand, the book also taps into popular, skeptical ideas about the origins of the church that are currently being taught in religion classes at secular universities.

Michael Licona, director of apologetics and interfaith evangelism for the Southern Baptist Convention’s North American Mission Board in Atlanta, agrees that Christians need to address the book’s sometimes outlandish claims, because more reputable scholars will take advantage of the media spotlight to promote their own brand of revisionist church history.

Chief among these, he says, is the theory that there were many forms of Christianity before “proto-orthodox” church authorities squelched the others and branded them “heresy” — a theory that was recently promoted in conjunction with the so-called Gospel of Judas.

“When the book mentions that Jesus was not thought of as the divine Son of God until the Council of Nicea in 325, that is easily refuted, because the deity of Jesus is peppered throughout the New Testament,” says Licona. “But even though the major claims of The Da Vinci Code can be answered easily, more moderate forms of those claims are presented by radical scholars such as Bart Ehrman and Elaine Pagels, and these need to be addressed.”

Ward Gasque, a Washington-based church historian with ties to Vancouver’s evangelical community, says Christians need to understand their own history better, so they can counter the story’s claims. “The reason 17 percent of all Canadians believe this, and it’s true virtually worldwide, is that they don’t know anything about history. But that’s true of most active Christians as well. They don’t know anything about what happened between the end of the first century and the Protestant Reformation, and therefore it seems plausible.”

–

The claims of The Da Vinci Code have come under renewed scrutiny recently. In February, Brown and his publishers were sued for plagiarism by Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, two of the authors of Holy Blood, Holy Grail, a 1982 book which claimed that Jesus faked his death, married Mary Magdalene, and sired a dynasty of French kings.

The earlier book is mentioned by name in The Da Vinci Code as one of its sources, and the character of Sir Leigh Teabing, who is played in the movie by Sir Ian McKellen, is named after the two co-authors. (“Teabing” is an anagram of “Baigent”.)

However, Brown told reporters outside the London courtroom that he did not subscribe to the belief that Jesus faked his death. “This is not an idea that I would ever have found appealing. Being raised a Christian and having sung in my church choir for 15 years, I’m well aware that Christ’s crucifixion is the very core of the Christian faith,” he said.

In a statement he issued to the press, Brown also hinted that he might believe in the Resurrection, too, in some sense. “Suggesting a married Jesus is one thing, but questioning the Resurrection undermines the very heart of Christian belief,” he wrote.

Some evangelicals agree that the book’s claims regarding Jesus’ alleged marriage to Mary Magdalene are among the least of its historical problems.

In addition to dismissing the divinity of Christ, Brown’s characters assert that the fourth-century emperor Constantine “commissioned” the canonical gospels and “shifted” the day of rest to Sunday, to coincide with pagan sun worship. In an earlier novel, Angels & Demons, the character Robert Langdon (who is played by Tom Hanks in the movie version of The Da Vinci Code) even claims that “Holy Communion was borrowed from the Aztecs”.

Many of these claims are easily refuted. Christian or European explorers did not encounter the Aztecs until the 16th century; and the fact that Christians met on Sunday to honour Christ’s resurrection is attested by several first- and second-century sources, such as Pliny the Younger and Justin Martyr — as well as St. Paul, in I Corinthians 16:2.

“The thing about Mary, that’s not that important,” says Licona. “What does matter is the divinity of Christ, and the claim that Christianity borrowed from pagan religions.”

Bock agrees. “I think the really important discussions are the ones that relate to the origin and development of Christianity,” including the formation of the New Testament canon, he says. “Whether Jesus was married is an interesting question, but in the end, despite the novel’s claims, it doesn’t have any impact on Christianity one way or the other.”

Other observers say the book’s references to the marital status of Jesus do matter. Barbara Nicolosi, executive director of the Act One screenwriting program in Los Angeles and a former Catholic nun, says the book’s claims undermine the traditional belief that Jesus is the bridegroom of the entire church. And she takes issue with the notion that the people attracted to the book and movie versions of this story are “seeking the truth.”

“No they’re not. If people were seeking the truth, they would be buying the Catechism and enrolling in theology courses,” says Nicolosi. “This book plays to a deep instinct, which is that if Jesus is a sham, then I don’t have to change my life. I don’t have to repent, I can ignore the church. And that is what is behind The Da Vinci Code.”

–

However, Gasque says some of the book’s fans may be seeking the truth after all. He says he’s been “having an awful lot of fun” giving dozens of lectures about The Da Vinci Code over the last few years, and it has brought him a new kind of audience.

“If the event is publicized widely, about a third of the audience will be from outside of the sponsoring church — some of them from other churches, but some of them totally unchurched,” he says. “Now when I give lectures on the Book of Acts, nobody shows up who is unchurched.” He says the movie provides a “wonderful opportunity” to share the faith.

Many Christians have prepared for the arrival of the movie by writing Da Vinci Code-related books and creating websites featuring sermon ideas and other resources; evangelical heavyweights like Josh McDowell and Lee Strobel have weighed in at Outreach.com, while Catholics have set up websites like DaVinciOutreach.com and JesusDecoded.com.

In addition, over 40 commentators representing Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox churches have written critical essays for TheDaVinciDialogue.com. The website is sponsored by Sony Pictures Entertainment, the studio behind The Da Vinci Code, in conjunction with Grace Hill Media, a company that specializes in promoting movies to the religious media.

The latter site includes news links provided by HollywoodJesus.com, whose founder David Bruce says the movie should be good for “water cooler conversations” about the faith.

“It’s a perfect film to begin dialogue on faith,” he says. “There are very few movies that come down the pike that are big, well publicized, and have such wonderful connections for spiritual conversation. So that makes this movie very positive, in my view.”

Others, however, are not so impressed. Nicolosi says Christians have become so concerned about appearing “hip” and not being rejected by the secular world that they have allowed themselves to be co-opted by the corporate forces behind the movie.

“Is slander an opportunity for dialogue? Is libel an opportunity for dialogue?” she asks. “Everything is an opportunity for dialogue, but the question is, are we framing the dialogue? And the answer is no, and anybody who thinks otherwise is kidding themselves. The dialogue is completely being framed by Sony Pictures and Dan Brown.”

Because Hollywood places so much emphasis on a film’s opening-weekend box-office take, Nicolosi recommends that Christians who believe they need to see the film for pastoral reasons put off going to the movie until at least the second weekend.

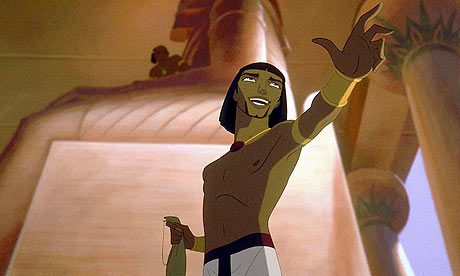

In addition, she has proposed that Christians make a point of going to see the DreamWorks cartoon Over the Hedge, which opens the same week. “What we would love to do is push a few more million in that column and take it off of Da Vinci,” says Nicolosi. “All Hollywood listens to is the box office, and if the Christians don’t see this movie, it tanks.”

Licona concedes that Christians will probably not have to see the film to discuss the claims made by the book. But he still says seeing the film can provide a point of contact with people who have seen the movie and want to discuss the ideas it presents. “Paul was willing to engage in critical discussions with nonbelievers, and so should we,” he says. “And if we don’t see the movie, we can’t discuss it critically and intelligently with others.”

Bock says it is important that Christians know their church history first. “I think the opening up of these issues has been a very good thing, and if it produces the kind of dialogue about the real Jesus that it can generate, and if the church can get itself into a position to understand its own history and theology, then that will be a good thing for the church.”

Licona adds, “I know there are Christians who will say I don’t want to give money to Hollywood and I know they’re doing it for the money, and they’re absolutely right, and this is something they’ll have to follow their consciences on. For myself, I think the outreach opportunities outweigh the negative of giving money to Hollywood and Dan Brown.”

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.