In 1961, Metro–Goldwyn–Mayer produced King of Kings, the first major Hollywood film about the life of Christ since the silent era. The virgin Mary was played by Siobhan McKenna, a respected Irish actress in her late 30s, and the villainous Herod the Great was described by the narrator as “an Arab of the Bedouin tribe.”

In 1961, Metro–Goldwyn–Mayer produced King of Kings, the first major Hollywood film about the life of Christ since the silent era. The virgin Mary was played by Siobhan McKenna, a respected Irish actress in her late 30s, and the villainous Herod the Great was described by the narrator as “an Arab of the Bedouin tribe.”

Nearly half a century later, things have flipped around. The Nativity Story, produced by New Line Cinema (the same studio that made The Lord of the Rings), casts an Irishman as King Herod; and several of the supporting actors were born in primarily Muslim territories, such as Iran and Sudan, or can trace their family roots there.

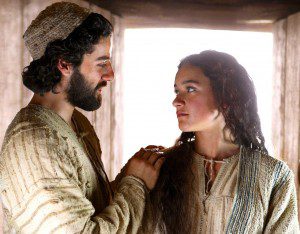

Mary in the new film is played by Keisha Castle-Hughes, a 16-year-old New Zealander who was nominated for an Oscar for her role in Whale Rider. Although Castle-Hughes is part Maori, this is at least the second time she has played a Middle Easterner; two years ago, she played an Arab–American in a music video by Prince.

Gone are the days when blue-eyed, blonde-haired actors and actresses could pass themselves off as the Jewish Messiah or his immediate friends and family. Audiences expect more “authenticity” these days, and filmmakers eager to promote their films as something new and different are more than willing to provide it.

Even Mel Gibson, who faced a firestorm of controversy over allegedly anti-Semitic elements in The Passion of the Christ, made a point of altering the appearance of actor James Caviezel (through make-up, and by digitally turning his eyes from blue to brown) in order to make his Jesus look more Jewish.

Some filmmakers have ventured into even more controversial territory. Color of the Cross, an independent film written and directed by Jean-Claude La Marre and released in the U.S. in October, depicts Jesus, Mary, and Joseph as black — and suggests that racial prejudice may have been a factor in the crucifixion.

La Marre has said he made his film to challenge the fair-skinned, fair-haired image of Jesus that has dominated Western art since the Renaissance. Interestingly, he does not deny the Jewishness of Jesus; when the Roman soldiers in his film set out to arrest Jesus, they snarl that they are looking for a “black Jew.”

Does ethnicity matter in Bible films?

On one level, yes. Jesus was Jewish, and early Christians were profoundly aware of their indebtedness to God’s chosen people. As Paul says in Romans 11:26, paraphrasing Isaiah 59, “The deliverer will come from Zion.” To the extent that we Christians may have forgotten the Jewish roots of our faith, we need to be reminded of this, and films that dramatize the Bible can help us remember.

But on another level, no. The message of the Bible is ultimately universal, and artists have a right — perhaps even an obligation — to explore the significance of Christ’s life and ministry for their own communities and their own points in history.

They can do this by filming the historical life of Christ using whatever actors happen to be available — as the British animated film The Miracle Maker did, by casting English and Welsh and Scottish actors for all the major voices; or as the Bollywood film Dayasagar did, by casting Indian actors as Jesus and his followers.

Or they can do this in a more allegorical way. Son of Man, a South African film that played at festivals in Canada and elsewhere this year, imagines what the life of Jesus might have been like if he had been born in a modern, war-torn African nation. By telling the ancient story in a modern setting, the film shows the relevance of Jesus’ teachings in today’s world. It can also open our eyes to certain political and cultural aspects of the Gospels that might not have occurred to us before.

Films like Color of the Cross present a dicier challenge. La Marre has said that African Americans need to be able to worship a God in their own image. The film serves a valid allegorical purpose, insofar as members of an oppressed minority can look to Jesus and believe that he shares in their suffering. But, projecting modern racial issues into the ancient story itself could be unnecessarily divisive.

The Nativity Story follows a safer route, depicting the mother and adoptive father of Jesus as the Mediterranean people they really were, and by depicting the virgin Mary as a teenaged girl, which she almost certainly was. It might seem a little odd to audiences who never think of the story’s historical roots, but that, in a way, is the message of the story. Sometimes something good can come from Nazareth.

Peter Chattaway reviews movies for a variety of periodicals as well as Christianity Today’s website. He lives in Vancouver.

— A version of this article first appeared in the Mennonite Brethren Herald.