I watched all the Rocky films (1976-1990) this weekend — all, that is, except for the sixth film, Rocky Balboa, which opens nine days from now. I had seen only one of them before, and that was on a high school retreat nearly 24 years ago, so it was kind of a fun marathon, watching all these films for the first time and charting the sometimes jarring shifts in tone and theme across the years.

Sylvester Stallone, like many other filmmakers these days, has been promoting the newest film to the religious media, and after seeing the first two films in particular, I’m not at all surprised.

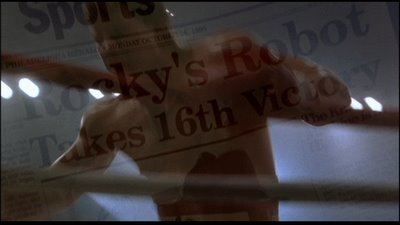

The opening shot in the first film (copied above) is of an icon of Jesus, and the second film lays the religious themes on pretty thick: not only does Rocky pray and/or cross himself before the climactic fight, as he does in virtually all of the films, but he visits a priest and asks him to send a blessing down from his window, and he prays without ceasing in the hospital’s chapel while his wife is in a coma, and he makes a point of thanking God after he wins his second fight against Apollo Creed. This is all in a film from 1979, remember, when no one felt a need to pander to a religious “niche”; it was just part of the character that Stallone created.

This is not to say that Rocky is a textbook “good Catholic”; he and Adrian apparently have sex before marriage, and Rocky is working with some pretty shady people at the beginning. But a lot of this may be explained — not excused, but explained — by the social circumstances into which the character was born. And given his surroundings, Rocky is a pretty decent guy.

The second film makes such a big deal out of how uncomfortable Rocky is with the fame and momentary fortune that come his way after his first match against Apollo Creed, that it is pretty jarring to see how the third film begins by showing how at-ease he is with fame and upper-class living so soon after the second match.

An entire sequence in the second film is devoted to a commercial shoot that fails because Rocky cannot read his cue cards, and because Rocky’s masculinity is threatened by the whole process (the scene begins with a swishy make-up artist using words like “finito” as he tries to make Rocky look like a “brute”). But in the montage that opens the third film, Rocky sits down for an ad wearing a suit and tie, no problem, and it’s on to the next thing.

I can appreciate that Stallone wanted to chart the rise and fall of this character over several films, and I can appreciate that Rocky’s career path follows Stallone’s to some degree, and thus the series is somewhat autobiographical. But I still would have liked to see more of the actual transition there, from socially awkward street tough to rich guy making tasteful use of his fame and money.

And then there is another sudden transition at the beginning of the fifth film, in which Rocky loses all his wealth, thanks to a bad financial manager, and moves back to the old neighbourhood — and suddenly he’s dressing and talking just like he did in the ’70s.

The religious stuff is largely forgotten in the third and fourth films, which celebrate the extreme materialism and patriotism of the 1980s. Rocky is briefly seen praying and/or crossing himself before the big fights, and that’s it; but by this point, the prayers have become part of the franchise’s routine, just like the training montages that end with Rocky pumping his fists in the air.

When Rocky moves back to the old neighbourhood in the fifth film, he visits the priest for another blessing, but again, it feels like little more than a repeat of a moment from an earlier film; in the second film, you could believe that Rocky was part of the local Catholic community, even if his involvement in it was kept largely offscreen, but now, after being away for so many years, we are given no reason to believe that he has integrated himself back into the community, so when he says, “I’ll see you in church,” the line has no weight. In fact, when the priest appears at the very end of the film to “bless” the rather vengeful street fight between Rocky and his former protégé, it feels like a trivialization of religion rather than a deeply felt acknowledgement of divine grace.

One of the peculiarities of the Rocky sequels is that each one picks up where the last movie left off, by re-playing the last scene from the last movie, yet most of the films seem to take place in the year in which they were released, and the characters age as quickly as the actors do. This leads to my favorite pet peeve, which is that there are some bizarre inconsistencies within the Rocky timeline.

The first film, which came out in late 1976, begins on November 25, 1975. The big fight at the end — billed as a “bicentennial” boxing match — takes place on New Year’s Day 1976.

The second film, which came out in June 1979, begins right after that fight, with Rocky and Apollo in the hospital, and it ends with a re-match on Thanksgiving Day, “ten months” after the previous match. So this film must also take place in 1976. I don’t think anything in the script contradicts this, although when Rocky buys his first car, it happens to be a 1979 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am.

The third film, which came out in May 1982, takes place “three years” later. We know this because Paulie says, “Three years, did you get me a job?” and because Mick says, “Three years ago, you was supernatural,” and because Apollo Creed says he got the idea for a private re-re-match “about three years ago.” So, if we ignore the Trans Am, this film should take place in 1979, right?

Uh, wrong. A newspaper headline is dated “May 15, 1982”. And when Mick dies — after the events described in that newspaper article! — the plaque on his final resting place says he died August 15, 1981. (And just to confuse things even more, in the fifth film, someone says Mick willed something to Rocky’s son “in 1982.”)

What’s more, the opening montage charting the rise of Rocky’s fame and fortune also shows him meeting Presidents Ford, Carter, and Reagan. Carter had a full four-year term, between 1977 and 1981, so there is absolutely no way a montage that begins during the Ford era could end “three years” later during the Reagan era.

Even weirder is the fact that Rocky Jr., who was born during the second film in late 1976, is played in the third film by Ian Fried, who was born in December 1974 and was thus at least six years old when the movie was shot. Yet when Adrian tells Rocky to shush late at night, she says, “You’re going to wake the baby.” Baby!?

On to the fourth film, which came out in November 1985. The third and fourth movies are bridged by a scene in which Rocky and Apollo have a private re-re-match, soon after Rocky’s successful defeat of Clubber Lang; and in the fourth movie, this is followed by a scene in which Rocky drives home and explains to Rocky Jr. that he got his black eye from a “friend”. Yet within minutes, he’s telling Adrian, “In case you forgot, it’s almost been nine years since you’ve been married to me.” So it’s no longer 1979, or 1981, or 1982, but 1985, then? Sure enough, the music, the fashions, the politics, and the giant talking robot (what’s up with that!?) all seem a little more advanced. And, oh, look, here’s another newspaper headline, this time copyrighted 1985:

So have Rocky and Apollo been meeting for fights on a regular basis over the past three, or four, or six years?

The fifth film, which came out in November 1990, begins minutes after the events of the fourth film, before Rocky has even had a chance to finish showering after the fight. But now, Rocky Jr. is played by Stallone’s real-life son Sage, who was born in 1976 and thus turned 14 shortly after this film was shot. And look, here’s another newspaper headline, this time dated October 1990:

Stuff like this drives me nuts. But a good kind of nuts.

This morning, I saw Rocky Balboa (or, if you prefer, Rocky VI), and while I obviously won’t review it until opening day, I can definitely say that the gap between this film and the others is so, so long that it doesn’t even try to pretend that it takes place right after the others, or to give us a montage that zips us forward a few years like the third film did. As far as chronology goes, it therefore presents none of the problems that the other sequels did.