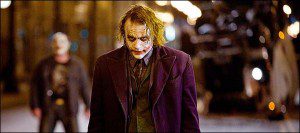

FOR YEARS, the people who write the Batman comics and movies have been drawn to the theme of insanity. The Joker is wild, of course, and so are many of the other villains; and it is often suggested that a billionaire like Bruce Wayne must be crazy on some level too, if he feels compelled to wear a bat-shaped costume every night just so he can prowl the streets looking for criminals to terrorize.

FOR YEARS, the people who write the Batman comics and movies have been drawn to the theme of insanity. The Joker is wild, of course, and so are many of the other villains; and it is often suggested that a billionaire like Bruce Wayne must be crazy on some level too, if he feels compelled to wear a bat-shaped costume every night just so he can prowl the streets looking for criminals to terrorize.

Thankfully, the two Batman films directed by Christopher Nolan have so far avoided this cliché. Instead of dwelling on the inner psychology of Batman, they have explored the social implications of the character, using him as a lens through which to raise profound questions about the nature of authority, the value of myths and the lengths to which any civilization should go in protecting itself from evil.

Batman Begins, which came out three years ago, was largely about fear: both the need to overcome it, and the possibility of inflicting it on those who are not yet afraid of judgment or punishment but probably should be. And now, The Dark Knight is about order and chaos, and how the gap between those two things is often filled by people who sacrifice themselves and their reputations for the greater good.

As the story begins, things are looking fairly good in Gotham City. Batman (Christian Bale) has struck terror into the hearts of the city’s criminals; and, without meaning to, he has also inspired a number of civilians to put on costumes and strike back against crime themselves — though he does not always approve of their methods, which leads some of them to ask what makes him all that different from them.

Most significantly, Gotham City has a new district attorney, a ‘white knight’ named Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart), who is determined to crack down on crime, and who seems to have the confidence of the citizenry. He also has Bruce Wayne’s sort-of ex-girlfriend, Rachel Dawes (Maggie Gyllenhaal), at his side, and has asked her to marry him. All these factors prompt Bruce to wonder if he should hang up the cowl and retire from crimefighting. Maybe, just maybe, Harvey can do — within the law — what Batman has been doing outside the law. And maybe, just maybe, Rachel will come back to Bruce and be his wife instead of Harvey’s, once he quits being Batman.

But before Bruce can say “mission accomplished”, things get worse – a lot worse. A new criminal called the Joker (a dynamic performance by the late Heath Ledger) arrives in Gotham and begins stirring things up: robbing banks, assassinating city officials and threatening to do a whole lot more damage unless Batman reveals his secret identity. The cops are sick of seeing their fellow officers killed in the line of duty, and they demand that Batman give himself up. But Harvey insists that, no matter how legitimate the complaints about Batman’s methods might be, the city dare not give in to a “terrorist” like the Joker by giving up its nocturnal hero.

And so the stage is set for a fascinating — and ultimately tragic — look at the nature of heroism and villainy and how these things are present in all people, to varying degrees. The heroes succeed to the extent they do partly by scaring people into thinking they, the heroes, are capable of criminal deeds themselves, even though they have no intention of actually doing anything quite so bad — but one of the questions that lingers over the film is whether, deep down, these heroes might really be capable of such things if push comes to shove.

For his part, the Joker believes that few, if any, people are really all that good — they are only good to the extent that the world lets them be good, he says — and his various crimes are increasingly designed not for personal gain nor even to defeat Batman, as such, but to prove his point, that in a world without rules, everyone is capable of becoming a selfish, murdering monster just like him.

This is heady stuff for a comic-book movie, and it has already prompted a handful of critics to complain The Dark Knight is an exercise in nihilism. But there is heroism here, too, and it sometimes comes from the most unlikely of places. Bruce Wayne’s butler, Alfred Pennyworth (Michael Caine), remains a source of courage to him; and his gadgets expert, Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman), becomes his conscience.

And, thankfully, the film’s complex view of human nature allows for bold, principled displays of self-sacrifice, even as it acknowledges that people are fallen and weak and capable of tolerating great evil when it is done in their name. It is a moral lesson reminiscent of Ratatouille: just as that film suggested not everyone could be a great chef, but that great talent could come from anywhere, so too The Dark Knight proposes that not everyone may be a hero, but heroism can come from anywhere.

In its own way, that is a very inspiring message — and it comes in this film when you least expect it. There is a lot more which could be said about this film, but it would mean getting into all sorts of plot details the viewer should experience for the first time in a proper movie theatre. So for now, suffice it to say The Dark Knight is easily one of the best superhero movies ever made, and it is one you may want to talk about for quite some time after the credits have rolled.

Internet Movie Database | Movie Review Query Engine

USA: PG-13 | BC: 14A | ON: 14A | QC: 13+

— A version of this review was first published in BC Christian News.