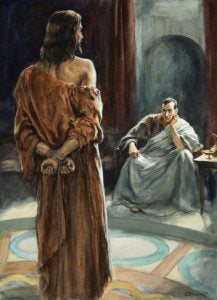

Deadline reports that Warner Brothers has acquired a script about Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator who condemned Jesus to the cross. No director is attached yet, but the script was written by Vera Blasi and the movie is set to be produced by Mark Johnson, whose credits include the TV show Breaking Bad and all three movies in the Chronicles of Narnia series.

Deadline reports that Warner Brothers has acquired a script about Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator who condemned Jesus to the cross. No director is attached yet, but the script was written by Vera Blasi and the movie is set to be produced by Mark Johnson, whose credits include the TV show Breaking Bad and all three movies in the Chronicles of Narnia series.

Deadline’s Mike Fleming, who has seen a draft of the screenplay, says it depicts Pilate as “a ferocious soldier” whose military exploits put him on “the political fast track” until the Roman emperor Tiberius assigns him to a position in Judea, rather than in Egypt as Pilate had expected. Fleming says the script “reads almost like a Biblical era Twilight Zone episode in which a proud, capable Roman soldier gets in way over his head. His arrogance and inability to grasp the devoutness of the citizenry and its hatred for the Roman occupiers and their pagan gods leads him to make catastrophic decisions. All of this puts him in a desperate situation and in need of public approval when he is asked to decide the fate of a 33-year old rabbi accused by religious elders of claiming he is King of the Jews. Along the way, . . . Roman emperors including Caligula and Tiberius and New Testament figures like John the Baptist, Salome and Mary Magdalene are seen in a tale that culminates with Pilate’s fateful decision to allow Jesus Christ to be crucified.”

I am not quite sure what to make of Deadline’s claim that the script “culminates” with the crucifixion, if the script also features the Roman emperor Caligula, whose reign did not begin until several years later. Perhaps Caligula, who was still a teenager at the time of the crucifixion, pops up as a member of Tiberius’s entourage or something. Or perhaps the movie will go on to show how Pilate’s ham-fisted rule of Judea came to an end several years later, when he was called back to Rome and arrived shortly after Tiberius’s death, by which point Caligula had become emperor.

Either way, it will be interesting to see how the film navigates the relationship between Roman and Jewish politics — to say nothing of how it will navigate the relationship between the Christian and non-Christian Jews. It is common, in Christian depictions of the trials of Jesus, to depict Pilate as a somewhat hapless Gentile who genuinely believes in Jesus’ innocence but lets the Jewish leaders bully him into signing Jesus’ death warrant. (Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ arguably fell into this error, or one much like it, by depicting Pilate as thoughtful and reserved, in contrast to the more explicit villainy of that film’s Jewish leaders.) But the gospels themselves — especially Luke — cast a slightly more negative light on Pilate, and this negative impression is deepened by the other Jewish accounts of that era.1

The fact that this film is going to portray Pilate as “a ferocious soldier” suggests that the filmmakers might be on the right track, as far as Pilate’s brutality is concerned. Then again, Fleming also writes that the film will combine “history, political maneuvering and storytelling inventions reminiscent of such films as Braveheart and Gladiator,” which, given how utterly non-historical the “storytelling inventions” in Braveheart and Gladiator were, is cause for some concern. Still, we’ll see.

– – –

1. For more on Pilate’s reputation in the secular sources of that era, and the implications for how we ought to read the gospel accounts, consider this passage from N.T. Wright’s Jesus and the Victory of God:

Pilate was not, by any account, a particularly competent or distinguished official. His rule in Judaea was often provocative and bullying. Philo’s description of him, though undoubtedly exaggerated for rhetorical effect, is worth quoting. He describes the incident in which Pilate placed golden shields in the Herodian palace, causing offence which was, for Philo, a foretaste of what would have happened had Gaius’ plan to erect a statue of himself gone ahead. He tells how a delegation of princes confronted Pilate, threatening to tell Tiberius what was afoot. Pilate’s reaction is revealing:

He feared that if they actually sent an embassy they would also expose the rest of his conduct as governor by stating in full the briberies, the insults, the robberies, the outrages and wanton injustices, the executions without trial constantly repeated, the ceaseless and supremely grievous cruelty. So with all his vindictiveness and furious temper, he was in a difficult position. He had not the courage to take down what had been dedicated nor did he wish to do anything which would please his subjects. At the same time he knew full well the constant policy of Tiberius in these matters…

Even on the correct assumption that Philo has over-egged the pudding, his picture is not so very different from that of Josephus. The scholarly spectrum of opinion on Pilate is not particularly wide, ranging from those who think he was an unmitigated disaster to those who, like Brown, say merely that he was ‘not without very serious faults’. The interesting thing to note for our present discussion is just how similar, underneath the rhetoric, Philo’s account of the ‘shields’ incident is to John’s account of Jesus’ trial before Pilate. In both incidents, Pilate is caught between his desire not to do what his Jewish subjects want — he intends to snub them if he can — and his fear of what Tiberius will think if news leaks out. ‘If you let this man go, you are not Caeasar’s friend.’

This raises the point at issue in our present discussion. It has been fashionable for some time to say that the evangelists increasingly whitewashed Pilate’s character in order to lay the blame for Jesus’ death on his Jewish contemporaries. But proponents of this view never quite come to terms with the fact that if John and the rest were trying to make Pilate out to be anything other than weak, vacillating, bullying, and caught between two pressing agendas neither of which had anything to do with truth or justice, they did a pretty poor job of it. The later Christian adoption of Pilate as a hero, or even a saint, is many a mile from his characterization in the gospels: the famous scene of Pilate washing his hands must surely be read, both within history and within Matthean redaction, as merely the high-point of his cynicism. He was the governor; he was responsible for Jesus’ death; washing his hands was an empty and contemptuous symbol, pretending that he could evade responsibility for something that lay completely within his power. What emerges from the records is not that Pilate wanted to rescue Jesus because he thought he was good, noble, holy or just, but that Pilate wanted to do the opposite of what the chief priests wanted him to do because he always wanted to do the opposite of what the chief priests wanted him to do. That was his regular and settled modus operandi.