Four years ago, I wrote a blog post on The Big Fisherman (1959), one of the more obscure Bible movies ever released by a major Hollywood studio.

Four years ago, I wrote a blog post on The Big Fisherman (1959), one of the more obscure Bible movies ever released by a major Hollywood studio.

As far as I know, the film, which was originally distributed by Walt Disney’s Buena Vista division, has never been officially released to home video, at least not in North America. But I had read a bit about it in books on the history of Jesus movies — the title refers to the apostle Peter — and I was intrigued by the information I found at the Internet Movie Database.

For one thing, the film is based on a novel by Lloyd C. Douglas, who also wrote The Robe, which 20th Century Fox turned into a much more famous film in 1953. For another, it seemed that this film might rely on the secular account of Herod Antipas and John the Baptist given to us by Josephus, which no other film I could think of had ever done.

And what did the apostle Peter have to do with any of this? I had no idea, but I was curious to find out.

Well, now my curiosity has been satisfied, because someone has posted a 140-minute version of the movie (which is apparently 40 minutes shorter than the version released to theatres way back when) on YouTube:

It’s not a very good film, alas (and the fact that the sound is slightly out of sync in the YouTube version above doesn’t help), but I don’t think it’s particularly terrible, either. And honestly, it gets bonus points from me just for covering a neglected aspect of biblical history — or, more accurately, for covering a semi-familiar aspect of biblical history from an angle that has been neglected by most other films.

On the other hand, for a film that is named after St. Peter, there is strikingly little of him in it, at least in this present version; he doesn’t even make his first appearance until about 40 minutes in, and he is absent for entire sequences afterwards. It’s a little reminiscent of how King of Kings (1961), the first major Hollywood movie about the life of Christ produced during the sound era, focused so much of its attention on the supporting cast that Jesus himself ended up being in less than half of the film.

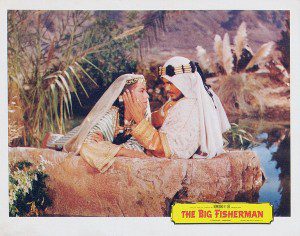

The main character in The Big Fisherman, it turns out, is Fara (Susan Kohner), an Arabian princess who discovers that her father is Herod Antipas (Herbert Lom), a Galilean king who divorced her mother and sent her home in shame after leaving her for Herodias (Martha Hyer), the wife of his brother Philip (Peter Adams).

Fara is told that many Arab noblemen have tried to assassinate Antipas in revenge for the dishonour that he brought to their kingdom, but so far they have all failed; so Fara disguises herself as a boy and makes her way to Galilee to see if she can kill Antipas herself.

First, given that this film was produced between the Arab-Israeli Wars of 1948 and 1967 (and only a few years after the Suez Crisis of 1956), it is interesting to see how the central character here is conflicted by the fact that she is “half-Arabian” and “half-Judean”.

The “half-Arabian” part is not inaccurate, as Fara’s grandfather, King Aretas (Stuart Randall), was king of the Nabateans, a group of nomads who lived in the Arabian desert and at least some of whom, according to Wikipedia, seem to have been “true Arabs”, based on the names they used in their inscriptions. It’s interesting, though, that the Nabateans depicted in this film all live in tents — even the royalty — and that there is no hint of the mighty architecture that they built in places like Petra (best-known to movie fans today as the setting for the final scenes in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade).

The “half-Judean” part is trickier, as Herod Antipas never had any authority over Judea, just Galilee. And while the Herodian family did practise Judaism on some level, they were, ethnically speaking, not Jews but Edomites (a.k.a. Idumeans); in fact, Antipas’s mother had been a Samaritan and his grandmother — i.e. the mother of his father, Herod the Great — was… wait for it… a Nabatean. So Fara would be five-eighths Nabatean, one-eighth Idumean and one-quarter Samaritan — but not Judean, depending on how narrowly we define that term.

In any case, the central dramatic arc of this film concerns Fara’s reconciliation of these two halves of her identity — and this, in turn, presumably represented the filmmakers’ desire for peace and reconciliation in the Middle East. It is not unlike how Cecil B. DeMille changed the ethnicity of Moses’ wife from Midianite to Ishmaelite in the 1956 version of The Ten Commandments, just a few years earlier, to underscore the idea that Jews and Arabs can be united, even in marriage.

Second, the chronology given by the film flips things around in some ways.

If Wikipedia’s summary of the historical events is accurate enough, Antipas married his first wife — called Phasealis by the historians and Arnon (Marian Seldes) by the film — shortly after his reign began (so, shortly after 4 BC), and they had been married for some time before he embarked on his affair with Herodias, probably in the mid-20s AD. Shortly afterwards, as per the gospels, John the Baptist condemned the marriage between Antipas and Herodias and was beheaded for his efforts. And then, in AD 36, the tension between Antipas and his ex-father-in-law flared up into open war, and Antipas’s defeat at the hands of Aretas was interpreted by the Jews as a sign of God’s judgment against Antipas for what he did to John. Finally, three years later, Antipas was sent into exile when Herod Agrippa I — Antipas’s nephew and Herodias’s brother — accused Antipas of conspiring against the emperor Caligula.

If Wikipedia’s summary of the historical events is accurate enough, Antipas married his first wife — called Phasealis by the historians and Arnon (Marian Seldes) by the film — shortly after his reign began (so, shortly after 4 BC), and they had been married for some time before he embarked on his affair with Herodias, probably in the mid-20s AD. Shortly afterwards, as per the gospels, John the Baptist condemned the marriage between Antipas and Herodias and was beheaded for his efforts. And then, in AD 36, the tension between Antipas and his ex-father-in-law flared up into open war, and Antipas’s defeat at the hands of Aretas was interpreted by the Jews as a sign of God’s judgment against Antipas for what he did to John. Finally, three years later, Antipas was sent into exile when Herod Agrippa I — Antipas’s nephew and Herodias’s brother — accused Antipas of conspiring against the emperor Caligula.

In the film, however, Antipas marries Arnon and divorces her while his father is still alive (so, some time before 4 BC); indeed, Aretas launches his attack against Jerusalem in retaliation for the divorce — and wins — the day after Herod the Great dies. And yet, somehow, all of this is said to be taking place during the reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius (who ascended to the throne in AD 14, nearly two decades later). And why is Antipas being crowned tetrarch of Galilee while his father is still alive, anyway? Wouldn’t that have happened after his father’s death?

And, needless to say, this is all taking place years before John the Baptist (Jay Barney) begins his ministry in the late 20s AD. So now, when Antipas executes John, the public’s condemnation of him has to express itself in a different way; instead of taking satisfaction in Antipas’s defeat at Aretas’s hands, the public turns against Antipas in a way that prompts the Romans to intervene for the sake of public order. Antipas can’t keep things under control, so someone else will have to do so in his place.

The first half-hour is spent setting up the dynamic between Fara and the Arab princes who dream of succeeding the current Arabian king. One of them says Fara cannot be his queen, because she is half-Judean, but he can make her his “favorite”, presumably as a concubine.

But Fara is closer to another prince, named Voldi (John Saxon), whose name I’m afraid I can never hear without thinking of Voldemort. When Fara sets off for Galilee, to kill her father, it is Voldi who follows her — with his father’s blessing — to try and stop her.

Thirty-five minutes into this movie about St. Peter, we finally meet our first major biblical character, apart from the Herods — and it’s John the Baptist. The film seems to suggest that John has at least a modicum of healing power, when he touches Fara’s head, which is interesting, since John is one of the few major figures in the New Testament who doesn’t have any such power. (Jesus and the apostles, yes; John, not so much.) John also gives Fara some food, and says not to pay him because he will be provided for. (Luckily for Fara, he gives her something better than the locusts and wild honey that were his main diet, at least according to the gospels.)

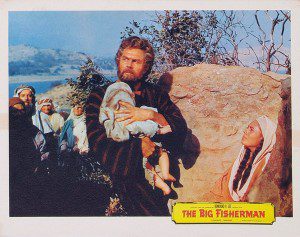

Forty minutes into the film, we finally meet Peter himself, and in such an abrupt way I can only assume some scenes are missing.

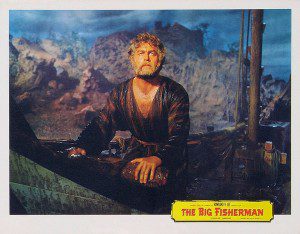

Peter is played by Howard Keel, an actor who was primarily known at that time for his starring roles in musicals such as Annie Get Your Gun (1950), Show Boat (1951), Calamity Jane (1953), Kiss Me Kate (1953) and — my personal favorite — Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954). (Apparently, years later in the ’80s, he found an all-new fanbase as one of the co-stars on Dallas.)

Keel was good at playing blowhards with a heart of gold, and that persona serves him well as Peter, who has often been played as a somewhat blustery and argumentative fellow; think James Farentino in Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth (1977).

When we first meet him, Peter is an impious sort who is on the verge of firing James (Tom Troupe) and John (Brian G. Hutton), the sons of Zebedee (Leonard Strong), for becoming obsessed with the teachings of “that carpenter”, i.e. Jesus.

When we first meet him, Peter is an impious sort who is on the verge of firing James (Tom Troupe) and John (Brian G. Hutton), the sons of Zebedee (Leonard Strong), for becoming obsessed with the teachings of “that carpenter”, i.e. Jesus.

This might be our first reference to Jesus in the entire film, and it’s interesting that it comes so soon after the film introduces us to John the Baptist, but without any clear depiction of the baptism of Jesus or the relationship between the John and Jesus movements (in this version of the film, at least). This omission is all the more remarkable because, in the gospels, Peter’s brother Andrew (Rhodes Reason) actually starts out as a follower of John’s and ends up introducing Peter to Jesus — but Andrew has almost no role to play in this film, at least as far as I noticed.

In any case, the scene where Peter fires the sons of Zebedee is also noteworthy because he whacks them on the side of the head as they leave. (The way he sends them off made me wish that Keel had gone all Adam Pontipee, his Seven Brides character, and said “Now git!”) This sets Peter up for an awkward moment later on when he hears Jesus teach that we should “turn the other cheek”. Sayings like that have a way of becoming proverbial and overly familiar, so a few Jesus movies have dramatized the actual striking and/or turning of cheeks, to make the saying come alive — though at the moment, the only specific example I can think of is Roger Young’s Jesus (1999), where Jesus himself is struck on both cheeks. The Big Fisherman is interesting, however, in that, here, the dramatic focus is not on the turning of the cheek but on the shame that is eventually felt by the one who struck the cheek in the first place.

Peter meets Fara and falls for her disguise, and so, thinking that she is a man, he decides to give her a place to stay, and he takes her home to his mother-in-law, Hannah (Beulah Bondi), who quickly figures out that Fara is actually a woman. Interestingly, we are told that Peter’s wife is dead, and there are no references to any offspring, though a brief reference to Peter’s wife in one of St. Paul’s epistles would seem to indicate that she lived for some time after this, and there is at least one apocryphal account to the effect that Peter might have had a daughter.

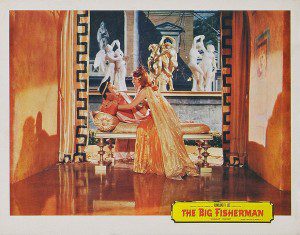

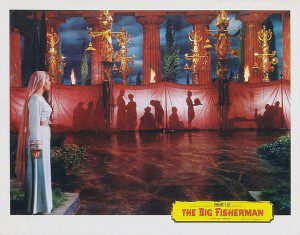

In any case, Fara applies for a job in Antipas’s palace so that she can get close enough to kill him one day, and she quickly gets a job — as a translator of Greek scrolls. The implication here seems to be that Antipas himself doesn’t know any Greek, which seems highly unlikely to me. In any case, Fara’s position within the palace gives her an opportunity to meet John the Baptist again, after he is arrested — and it also puts her in a position to witness the martyrdom of John first-hand (or, more accurately, in silhouette).

In any case, Fara applies for a job in Antipas’s palace so that she can get close enough to kill him one day, and she quickly gets a job — as a translator of Greek scrolls. The implication here seems to be that Antipas himself doesn’t know any Greek, which seems highly unlikely to me. In any case, Fara’s position within the palace gives her an opportunity to meet John the Baptist again, after he is arrested — and it also puts her in a position to witness the martyrdom of John first-hand (or, more accurately, in silhouette).

It’s interesting to see how this film’s depiction of Antipas borrows elements of his depiction in the gospels without precisely copying them.

For example, before he arrests John the Baptist, he wonders if John might be one of the Wise Men his father sent to Bethlehem — which echoes the paranoia he shows in the gospels later on, when he wonders if Jesus might be John come back to life.

Similarly, when he meets Fara, he almost seems to come on to her (apparently because she resembles his first wife, i.e. her mother), which might be semi-understandable since he doesn’t know yet that she is his daughter, but still, it’s icky in a way that recalls his obsession with his stepdaughter in the gospels. (Incidentally, that stepdaughter seems to be utterly missing from this film, so her role in John the Baptist’s execution is also curiously absent from the film.)

And then, later on, when Antipas does discover that Fara is his own daughter, he says he “might almost believe” that Fara is her mother come back to life — which, again, and even more explicitly, echoes the paranoia he shows in the gospels.

Anyway, somewhere in the midst of all this, Peter joins the Jesus movement, and so we get our first glimpse of Jesus somewhere about half-way through this version of the film. “Glimpse” might not be quite the right word, though, since this film, like every other Hollywood movie made during the sound era up to this point, keeps Jesus (or at least his face) out of the frame and lets us hear his words instead. And, unsurprisingly, these words are spoken in a King James English that none of the other characters ever use.

Anyway, somewhere in the midst of all this, Peter joins the Jesus movement, and so we get our first glimpse of Jesus somewhere about half-way through this version of the film. “Glimpse” might not be quite the right word, though, since this film, like every other Hollywood movie made during the sound era up to this point, keeps Jesus (or at least his face) out of the frame and lets us hear his words instead. And, unsurprisingly, these words are spoken in a King James English that none of the other characters ever use.

The film does focus on people’s reactions to Jesus and his words in an interesting way, though. I already mentioned how Peter reacts awkwardly when Jesus tells people to “turn the other cheek”. But Fara, too, is disturbed when Jesus tells people to love their enemies — so disturbed, in fact, that she puts her hands over her ears for a moment, and then leaves. There are other members of the crowd who instantly acclaim Jesus, some using messianic passages from the Old Testament, but the film does allow that a change of heart might take a bit longer for some people.

Jesus appears a few more times in this film — calling Peter and the other earliest disciples to be “fishers of men”, asking the disciples “Who do you say that I am?”, and healing Peter’s mother-in-law — but that’s about it.

Eventually the story returns to its principal focus, which is Fara’s quest for revenge and Voldi’s quest to stop her from getting that revenge — and Peter himself gets involved, declaring, “We must find a way to help these young people!”

Peter’s efforts in this regard eventually put him in touch with the royal houses of both Galilee and Arabia, which is a striking difference from the biblical record, where Peter does not seem to have had much if any interaction with the secular authorities at all (apart from Herod Agrippa’s futile attempt to have him executed).

In this regard, the film’s Peter is more like the biblical Paul, who testified before kings and procurators, and who even fled Damascus early in his career because the governor appointed by Aretas (yes, the very same Aretas that we’ve already mentioned here!) was out to get him (II Corinthians 11:32-33; a slightly different account of this episode in Acts 9:23-25 omits any reference to Aretas or his governor).

In any case, the last time we see Antipas, he is informed by a Roman that the emperor will probably take his kingdom away soon, because of all the popular unrest out there (though this didn’t actually happen for another decade or so — and when it did, the Romans gave his kingdom to Agrippa, rather than take direct control of it themselves), and he asks Peter to take care of Fara, who has finally overcome her hatred of Antipas and is now returning to Arabia.

In any case, the last time we see Antipas, he is informed by a Roman that the emperor will probably take his kingdom away soon, because of all the popular unrest out there (though this didn’t actually happen for another decade or so — and when it did, the Romans gave his kingdom to Agrippa, rather than take direct control of it themselves), and he asks Peter to take care of Fara, who has finally overcome her hatred of Antipas and is now returning to Arabia.

And so the last 15 minutes or so take place back in those tents in the desert where this movie began. Presumably, the death and resurrection of Jesus have not yet happened, so this part of the story is basically taking place at a time when the Jesus movement was still primarily focused on Palestine and had not yet spread beyond those borders — but Peter makes his way to Arabia anyway, where we find that the previous king has died, and one of the other princes (the one who threatened to make Fara his “favorite” concubine) has become king, and this new king asks Peter to heal him.

Peter replies that the king must first have faith in God, and the king complies and makes a vow or two, including a promise to release Fara from all his claims on her; but then, almost as soon as the healing has taken place, the king turns proud and says that Peter could not have healed him unless the power was already inside him, the king.

The king is in the middle of accusing everyone of treason for not following his vow-breaking orders, when suddenly he drops dead — and while this whole episode is entirely fictitious, it vaguely echoes yet another episode in the New Testament that has a sort of tangential connection to Peter: in Acts 12, Peter’s escape from Herod Agrippa’s prison is immediately followed by the story of Agrippa dying a sudden, public death because he accepted a crowd’s praise that he spoke with “the voice of a god, not a man.” The crowd in the film might not feel this way about its own king, but the king himself asserts his own divinity as Agrippa did, and dies as he did.

This scene in the film might also echo an episode from Acts 5, where Ananias and Sapphira drop dead after Peter accuses them of “lying to the Holy Spirit”.

This scene in the film might also echo an episode from Acts 5, where Ananias and Sapphira drop dead after Peter accuses them of “lying to the Holy Spirit”.

In any case, as the movie comes to an end, Voldi is now the king of Arabia, and, as much as he would love to marry Fara, he says he cannot, because he cannot break his own laws (which prevent a “half-Judean” from becoming queen) if he is to be the king.

So Fara stays with Peter, who says it looks like a good day for fishing, and a closing voice-over reminds us that the two greatest commandments are to love God and love our neighbour. And that’s how the movie ends.

While it’s a very obscure film nowadays, The Big Fisherman apparently got enough attention back in the day to be nominated for three Oscars: for cinematography, art direction and costume design. Not surprisingly, it lost in all three categories to the Charlton Heston-starring remake of Ben-Hur (1959).

A few of the film’s actors appeared in other Bible films in the years that followed.

The most noteworthy example is Herbert Lom (Herod Antipas), who went on to play Barnabas in Peter and Paul (1981); he is, of course, best known for playing Chief Inspector Dreyfus in seven Pink Panther movies between 1964 and 1993.

In addition to him, John Saxon (Prince Voldi) went on to play Adoniijah in an episode of Greatest Heroes of the Bible (1978); Tom Troupe (James son of Zebedee) had a supporting role in the one-hour TV special The Thirteenth Day: The Story of Esther (1979); and Alexander Scourby (David Ben-Zadok) went on to become an audiobook pioneer, a gig which included recording the entire Bible to audiocassette and, thus, narrating the Jesus film (1979) and other films made by the Genesis Project.

And, perhaps most amusingly, Marian Seldes — who, in The Big Fisherman, plays the first wife that Herod Antipas abandons for Herodias — went on to play Herodias herself in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).