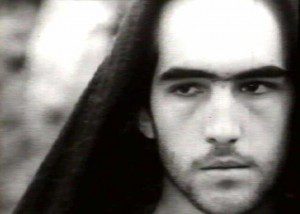

If you’ve seen as many Jesus movies as I have, then one of the things you cannot help but notice about Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel according to St. Matthew (1964) is its heavy use of close-ups.

If you’ve seen as many Jesus movies as I have, then one of the things you cannot help but notice about Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel according to St. Matthew (1964) is its heavy use of close-ups.

Later films about Jesus used their fair share of close-ups, too, of course — partly because many of them were made for television, at a time when the average TV set was still quite small — but Pasolini’s film, which was one of the last great Jesus films to be made for the big screen, is particularly intense in this regard.

In fact, Kevin B. Lee, a video essayist and editor of the always interesting Press Play blog, estimates that as much as forty percent of Pasolini’s film consists of facial close-ups. And to explore what that might mean, he posted a video essay at Fandor a few weeks ago, consisting of three parts: part one speeds through every close-up in the movie, part two focuses on the film’s shot-reverse shot sequences (which Lee says are “a critical device in the film”), and part three looks at a sequence that Lee finds especially “transformative … profoundly mysterious and unsettling”.

You can watch the video below, and read Lee’s comments on the video here.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZHtLzO-mbA

One extra comment, if I may, on the bit that Lee refers to as “the long sequence where Christ speaks in different locations and times of day”. I believe he’s referring to the Sermon on the Mount sequence, which has always been one of my favorite things about this film. To quote from an article that I wrote for the February 1998 issue of Bible Review, which I don’t believe has ever been posted online, this film, “wittingly or not, captured the format of the gospel in a way no film had before”:

Consider the Sermon on the Mount, which scholars agree is not a record of any one speech but a collection of Jesus’ sayings, each of which would have “required time for digestion” (Marcus Borg, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time, p. 71) to have the proper effect. Most films that tackle the sermon, before and after Pasolini, record it as one long monologue. Inadvertently, they usually end up showing just what would have made such a prolonged speech untenable in the first place. Such portrayals are not realistic as historical reenactments, nor are they compelling as cinema. Pasolini solved the problem brilliantly. He shot each saying separately, moving the camera toward Jesus’ face each time, and he edited the sayings into a montage. Although Jesus uttered each aphorism from the exact same spot, the audience was aware that chunks of time had been cut from between the sayings for the sake of expediency. Thus Pasolini preserved the Sermon’s redacted nature while making it watchable, even exciting.

If Lee is correct, then I may have been wrong about Jesus standing in “the exact same spot” for each clip in that montage. But the basic point remains: Pasolini made use of a cinematic device that matches the literary device used by Matthew’s gospel, and he did so in a way that sets his film apart and above from most other Jesus films.

Incidentally, if you haven’t seen the film before, you can apparently watch the whole thing online via YouTube, at least for now. Here it is:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h7ewh5k5-gY