What’s Wrong with Dethroning Sex?

I was inspired to write on the centrality of conjugal love after reading Todd Wilson’s book, Mere Sexuality: Rediscovering the Christian Vision of Sexuality, which presents the historical Christian vision of human sexuality. Within this survey, Wilson breaks new ground with a chapter on the sexuality of Jesus, and his spotlight on this neglected topic is both refreshing and relevant. However, many of Wilson’s conclusions within that chapter deserve more critical examination: “From the story of his [Jesus’] life, we learn that sexual activity isn’t essential to human flourishing or personal fulfillment…To be blunt, he didn’t need sex—not because sex is sinful or somehow beneath his dignity, but because sex isn’t essential to being human.” (49-50)

According to Wilson, if you accept that the celibate Jesus is fully and perfectly human, personally fulfilled, and resurrected in glory, then you must also accept that conjugal love is not essential to human fulfillment/being/flourishing. I would argue that Wilson ultimately sets up a false dichotomy here that is based on some problematic, underlying assertions.

First, if sexual activity isn’t essential to being human, what would Wilson consider essential? While he does go on to say that our sexual forms are central to being human (50), it’s important to flesh out this concept a bit more, because in doing so, we might discover that what we think of as “central” or “essential” to being human is somewhat debatable, even among Christians. In fact, the idea of essences has been deliberated for centuries, from Aristotle to Hegel, with some branches of philosophy (e.g., metaphysics) criticizing the validity of the idea of essences, their limitations, how essences are determined, etc. Wilson’s sweeping statement glosses over far too much without adequate exposition.

Second, I question if a binary concept of essences (essential/non-essential) is the best way to frame the relationship between sexual activity and human fulfillment/being/flourishing. If we are using essences as a paradigm, more nuanced categories of understanding beyond essential/non-essential may be helpful. For instance, what if a quality is generally, but not always, essential? The essentiality of any given quality may have dependencies or exceptions. Wilson doesn’t consider these subtleties, which become blindspots in his analysis that generate reductive conclusions.

Third, in his chapter on the sexuality of Jesus (chapter 2), Wilson draws conclusions about the relationship between conjugal love and human fulfillment/being/flourishing solely from the story of Jesus’ life – without a wider view of Scripture. While Wilson does discuss other relevant Biblical passages elsewhere in his book, those passages – and the important principles they convey – are oddly disconnected from the sweeping claims in this chapter, resulting in a tunnel vision that is not adequate to analyze any aspect of the Christian life. Again, there is the problem of reductionism.

Of course Jesus is the new Adam, the new human prototype, and we can glean valuable information on what it means to be human from his life; however, the Word of God on these matters is more than Jesus’ life. Wilson writes, “Somewhere along the way, Christians divorced the Bible’s teaching on human sexuality from the Bible’s teaching on the humanity of Jesus.” (40) Yet Wilson divorces his analysis of Jesus’ humanity, and what that means for human sexuality, from the rest of scripture.

I will attempt here to connect other Biblical passages on human sexuality with Jesus’ story, which I hope will offer (at least the beginnings of) a more cohesive and nuanced perspective on the relationship between conjugal love and human fulfillment/being/flourishing.

Note: I am more or less using the terms “sexual activity” (the term Wilson uses in his book) and “conjugal love” interchangeably, although I recognize that conjugal love specifically refers to marital sexual activity. My emphasis on conjugal love is intentional, as the Bible points to marital sexual activity as the ideal, and any discussion on the essentiality or centrality of sexual activity, from a Biblical standpoint, should make this distinction.

Deconstructing Wilson’s Claims about Conjugal Love

Let’s examine five of Wilson’s claims in more detail:

-

“From the story of his [Jesus’] life, we learn that sexual activity isn’t essential to human flourishing….”

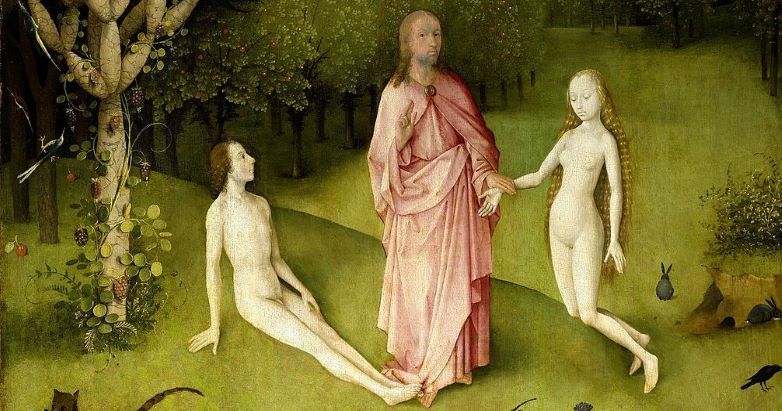

Stepping back to look at the entire story, not just the story of Jesus’ life or even of the Bible, but of our world, we see that sexual reproduction is key to human flourishing; without sexual activity, there simply are no humans who can flourish! This basic biological reality is part of God’s flawless design and crystallized in his first command to human beings: “Be fruitful and multiply.” (Gen. 1:28) These words of blessing dictate both God’s intention for our prosperity and the conditions (sexual reproduction) under which that prosperity, or fruitfulness, is actualized. You could say that in Eden, through the glorious design of our bodies, God establishes sexual reproduction as the means of human flourishing.

It is striking that God’s first words to us are an exhortation to make fruitful love. He could have simply said, “Worship me!” Yet through sexual activity, we worship God profoundly, not only by honoring his first command but because in doing so, we participate in the abundant love of the Trinity, the author of all creation, in whose image we are made (Gen. 1:26). Of course, we can “be fruitful and multiply” in non-sexual ways too; in fact, although sexual fruit is foundational to human flourishing, our prosperity depends on much more than that.

Wilson concludes that because the fully human, resurrected Jesus didn’t have sex, it’s not essential to human flourishing. What Wilson seems to overlook here, in addition to key passages in Genesis (and principles of biology), is that Jesus – the fully human, fully divine God-Man – is by definition exceptional. It’s no surprise that his short life, which was aimed at a cross (and the salvation of the world), does not include marriage, conjugal love, and the ensuing social and familial obligations. Jesus’ purpose was primarily to restore the world God made – a world where sex, by God’s design, is foundational to human flourishing; a world that God declared to be very good (Gen. 1:31) only after sex became possible, through the sexual differentiation of Adam of Eve.

While Jesus’ life certainly affirms the honor of celibacy – no small thing in his time or in ours – neither does his celibacy negate the general essentiality of sex to human flourishing. Instead, Jesus’ celibacy serves a functional theological purpose, enabling his mission to restore our fallen world, to restore Eden, to go back to the beginning, a beginning in which sexual activity, from God’s first words to us, is part of what defines our humanity – because it so beautifully reflects the life-giving love of the Trinity.

Genesis tells us more about the relationship between sexual activity and human flourishing than what Wilson derives from the narrow example of Jesus’ life. The wider view is important, because although Jesus proves that one can lead a celibate life and contribute massively to human flourishing, neither does Jesus’ celibacy disprove God’s general purpose for our biologically sexed bodies, which is the sexual activity that he makes essential – at the communal level, if not the individual one – to human flourishing. Although some people are called to celibacy, without sex, there would be no people (and no celibates) to speak of!

Interestingly, Wilson laments in Chapter 5 that sex in our current culture has become divorced from its procreative function and warns of the fatal consequences, noting that “babies” are the “future of the state.” (103-104). He clearly grasps the biological imperative of sex, but in doing so, contradicts his own notion in chapter 2 that sex (based on Jesus’ life) is not essential to human flourishing.

-

“From the story of his [Jesus’] life, we learn that sexual activity isn’t essential to…personal fulfillment…”

First, what does the rest of Scripture have to say on this matter? Second, does Jesus’ life really tell us that sexual activity isn’t essential to personal fulfillment?

To the first point, consider perfect, pre-Fall Adam. God saw that Adam was alone, deemed his isolation to be “not good” (Gen. 2:18), and determined that the key to Adam’s personal fulfillment, as it were, was nothing less than a sexually differentiated woman. In response to Adam’s aloneness, God might have said, “Just engage me more, Adam; then you’ll be fulfilled;” or, “I shall create other human brothers you can bond with; that’ll solve your problem.” No, God ordained that the sexually differentiated Eve was the perfect solution. Put another way, Adam’s aloneness, or lack of human fulfillment, was perfectly resolved, and only resolved, when sex became possible.

To the second point, Wilson twice asserts that Jesus was sexually contented (48, 59). But what is the basis for his claim? The Bible has nothing to say on Jesus’ sexual feelings. Perhaps Jesus longed for sex. Although Wilson admits that Jesus was tempted in every way that we are (55), his argument seems to hinge on an implied false dilemma: if Jesus experienced ultimate fulfillment in God, then we must accept that he was also sexually fulfilled. I would agree that Jesus found ultimate fulfillment/contentment in God, but we can’t extrapolate from this premise that he was contented/fulfilled in a particular sexual sense. Maybe Jesus had to forgo sexual contentment to accomplish the glory before Him. Thankfully, most of us don’t have to choose between sex and our vocations. But Jesus was the “man of sorrows” (Is. 53:3). He must have experienced extreme discontent in multiple facets of his life. That unhappiness did not have the final say; it did not preclude his ultimate fulfillment in God. But neither did his ultimate fulfillment in God preclude the visceral disappointments he endured and a lack of fulfillment in myriad ways, perhaps including sexual ones.

-

“He [Jesus] didn’t need sex…because…sex isn’t essential to being human.”

As mentioned under claim 1, I think it’s quite clear that the most immediate reason Jesus didn’t need sex is that sex wasn’t essential to – and in fact would have likely impeded – his mission to redeem the world, a world in which sexual activity (per divine decree) is an indelible part of our humanity, without which humans would not exist.

I noted in my introduction that Wilson does not discuss what qualities he would consider essential to being human (apart from advocating the centrality of our sexual forms, which I will discuss further under the next claim). I would argue that one of these qualities could be free will, or at least conditional free will, including the (conditional) freedom to choose our sexual activities. The choice to have sex reflects a constellation of factors, including our appetites, ethics, opportunities, limitations, and other circumstances. Therefore, while sexual activity may be generally essential to being human, as humans, we may also have the unique ability, through the exercise of free will, to override qualities – like sexual activity – that may be generally essential, without necessarily surrendering our humanity at all. Because the ability to override – through our wills – what may be generally essential to being human may be part of being human!

Perhaps a better conclusion to draw from Jesus’ celibacy, together with Genesis and other passages, such as the Song of Songs, is that sexual activity is generally, but not always, essential to being human. Jesus proves that sex isn’t always essential to being human without necessarily disproving the general essentiality of sexual activity to being human, as implied by our sexed bodies, and as dictated by divine and biological imperative.

The distinction between generally and always is subtle but important. It could be argued that if conjugal love isn’t always essential to being human, then it’s basically not essential to being human, which would make Wilson correct. However, I think more nuance is needed to describe the value of sexual activity beyond a polarity of essential/non-essential. Jesus’ celibacy does not negate the experiences of people who find in sex a unique fulfillment of their humanity. That is the experience of Adam and Eve. And that is the world Jesus came to restore. But neither do those experiences negate the humanity of Jesus – or of anyone else who is celibate. Wilson ultimately sets up a false dichotomy. We need better categories than “essential” or “non-essential,” with a wider view of Scripture, to understand the significance of sexual activity to being human.

-

“While sexuality (our being biologically sexed as male and female) is central to what it means to be human, sexual activity is not.” (50)

I think Wilson errs in the distinction of centrality that he makes between our sexed bodies and the purpose of those sexed bodies. Sexual activity is the natural order that proceeds from our embodied sexuality; our biologically sexed bodies are the antecedent of sexual activity. We see this dynamic at work in Eden through God’s first command to us, “Be fruitful and multiply,” immediately following our creation, which indicates the purpose, or function, that flows from our form. If form=function, and form is central to our humanity, it would seem difficult to argue that the function of that form is not central to our humanity; in fact, you could argue that the very purpose of the form is the function it entails.

Regardless, I don’t think the creation narrative allows us to disentangle the centrality of our sexed bodies from the centrality of sexual function in the way that Wilson would; the Genesis text seems to imply that the two are integrated and integral to our humanity. Yet, we have some freedom as individuals to choose our sexual activities, if not our biologically sexed forms, in a way that does not necessarily negate the general centrality of sexual activity to being human.

Notably, although Wilson makes a distinction of centrality between our biologically sexed bodies and sexual activity, he seems to argue in chapter 3 (“Male, Female and the Imago Dei”) that sexual activity and identity should be defined by our sexual forms. For example, he suggests that homosexual sex and transgenderism fall short in part because they contradict the sexual activity and identity conveyed by our biologically sexed bodies. Wilson’s point here is apt but somewhat ironic; if our sexual forms should dictate our sexual function, are celibates on a level playing field with individuals in same-sex sexual relationships? Both are denying the sexual function dictated by their sexual forms!

I highlight this paradox to further call out the contradictions that become apparent in Wilson’s expository vacuum. If he is going to claim that form=function, he also needs to reckon with the fact that celibacy involves a certain revocation of this formula. A more nuanced view that emphasizes the general centrality of conjugal love, as the purpose of our sexed bodies, would cohere better with some of Wilson’s claims in chapter 3.

The general centrality of sexual activity ultimately resonates with much of human experience. Many people are celibate, but many of those who are would rather not be, and the absence of sexual oneness is often experienced – perhaps even by Jesus – as a profound loss. Like Adam, we long for literal, physical communion with the other, in homage to our triune creator, who brands our bodies and souls with this sacred maker’s mark.

-

“Frankly, as a happily married heterosexual, I find it’s easy to forget (and tempting to resist the idea) that I don’t need sex to be satisfied.” (50)

This point, although the least of the five, is my favorite because it reveals how personal experience shapes our thinking.

Wilson makes the interesting assumption that his happy marriage – with seven(!) children, per his bio – makes it difficult for him to concede that sex isn’t necessary for his personal fulfillment.

I think Wilson could have it the wrong way around; perhaps it is his happy marriage and evidently blissful conjugal relations that make it so difficult for him to appreciate how essential sex is. Why? Because he can afford to take it all for granted! While I don’t begrudge him his marital/conjugal satisfaction – and I don’t believe it disqualifies him from drawing valid conclusions here – he shouldn’t tout it as “tempting” him to regard sex as essential. His sexual satisfaction is just as (if not more!) likely to keep from appreciating the essentiality of sex because, relatively speaking, it seems that he has never been without it in any meaningful way. It’s like a rich person saying, “Money is not essential, although I’m tempted, as a rich person, to believe that it is.” In fact, it may be easier to say that money isn’t essential when you have it. Try asking those struggling with lifelong poverty how essential money is; you might get a different response.

Similarly, with sex – try asking same-sex attracted Christians who struggle with celibacy how essential conjugal love is to personal fulfillment. Again, you might get a different answer than Wilson’s based on their experience of suffering. Perspective isn’t everything, but perspective matters here because it’s almost inevitable that we take for granted what is ever-present to us; that’s just being human. By appealing to the (potentially faulty) premise that his own fortuitous sexual circumstances bias him to view sex as essential, Wilson makes his argument on the non-essentiality of sex sound more valid than it really is.

Concluding Thoughts on the General Essentiality of Conjugal Love

Wilson could have made a much more accurate (and still provocative) statement to the effect of, “Jesus’ life invites us to consider how essential sex is to human flourishing/fulfillment/being,” that didn’t dodge the rest of the Bible. But Wilson doesn’t caveat his claims and bases them just on Jesus’s life. As a result, he draws conclusions that seem unsupported, and in some cases challenged by, other passages in Scripture.

Wilson’s chapter on the sexuality of Jesus seems intended to comfort people, particularly same-sex attracted Christians, who struggle with a lifetime of celibacy; the book itself he dedicates to Wesley Hill. Yet Wilson’s attempt to dethrone sex seems too heavy-handed and may not ultimately provide much reassurance to those who suffer with the pain of sexual brokenness. Why? Because his conclusion that sexual activity is not central to being human/human flourishing/personal fulfillment does not adequately account for the source, and intensity, of that pain. Maybe the reason why the pain of sexual brokenness can be so consuming is precisely because it cuts to the core of who we are as human beings: it’s just how we’re made.

Of course we shouldn’t worship sex. But if sex isn’t what we worship, it can be an essential part of how we worship. While I appreciate what Wilson is trying to accomplish in defending celibacy, his means of doing so – denying that sex is essential to human flourishing, being human, and personal fulfillment, based merely on Jesus’ life – is problematic. It feels like a knee-jerk reaction to a brokenly sex-obsessed world, ignoring basic biological realities along with the Bible, which at its center features a celebration of erotic love that is likened to the very flame of God (SoS 8:6).

Wilson says our fallen world errs in holding sexual activity to be imperative (51). I would argue instead that it is God – not our broken world – who made sex imperative, but the world’s response to that imperative is disordered. Wilson seems to conflate our world’s broken response to the sexual imperative with the validity of the imperative, which nevertheless carries an exception clause. The Bible is full of these exception clauses. As Rachel Held Evans points out in her book Inspired, quoting Proverbs 22:8: “You reap what you sow – except when you don’t.” Sex is divine imperative, sex is essential – except when it’s not. Except when it is. And so on.

Amid this tension, reclaiming the vital importance of conjugal love, rather than dethroning or minimizing it, may increase our capacity to show compassion to others, and ourselves, as we struggle in this area. If we don’t value conjugal love as the Bible does – as part of God’s first command to us and at the center of his holy Word – how can we truly commiserate with those who experience sexual devastation?

The unique circumstances of Jesus’ life are not the last word or the full story on the essentiality of sex to being human. What if we could acknowledge the full humanity and celibacy of Jesus (and of others) without denying the general essentiality of sexual activity in human life, as ordained by God? It’s difficult to hold these ideas together, perhaps as difficult as it is to conceive of a God who is three and one at the same time; yet, as Christians, we are called to wrestle with, not reduce, these glorious complexities.