Editors’ Note: This article is part of a Public Square conversation Women in Religious Leadership. Read other perspectives here.

The American Muslim community is eager to promote the notion that Islam is favorable to women’s leadership. We talk about the Prophet and how he encouraged women’s education, and praised his female companions for bravery in times of war. We quote verses from the Qur’an that demonstrate equality between the sexes. We point to Aisha and how she was respected as a scholar, or Fatima and her stand against injustice and tyranny, or Rabia and her devotion to a theology of Divine Love.

We point to strong, brave, powerful Muslim women in the modern world as the proof that our theology does in fact champion women’s leadership, both in a religious setting and in wider society. Women like heads of state Benazir Bhutto and Megawati Sukarnoputri, or Iran’s female police officers and Jordan’s elite women’s soccer team, women’s rights activists like Malala Yousafzai and Mukhtaran Mai and Shirin Ebadi, the first Muslim women to win a Nobel Peace Prize. We point to the quiet bravery of young Muslim American women who wear hijab in the face of a culture that is often hostile to their religion and the choice to cover. And we point to the countless Muslim American women who are activists, volunteers, speakers, and leaders in the Muslim community both locally and nationally. Often, these women cite their faith, their Islam as an inspiration to their leadership.

But despite this compelling evidence, dismal examples of women’s disempowerment abound in the Muslim world — from laws forbidding women in Saudi Arabia from driving, to women who are jailed for adultery after having been raped, to a tolerance for domestic violence, to legal requirements to cover head to toe, to mosques where women are not allowed at all, to the simple, daily fact that the millions upon millions of Muslim women live within a patriarchal family and social structure where men have more power and opportunity socially, economically, politically, and control nearly every aspect of their private and public life. And all too often, this disempowerment is based upon interpretations of Islamic law.

It’s enough to make your head spin, especially when you consider that some of the most powerful examples of female leadership come from countries where women have the worst legal status. Clearly, there are a whole lot of discrepancies in the Muslim world when it comes to women’s role in society, family, and religion.

This is, at least in part due to the fact that the Qur’an, and the Prophet, offer us multiple visions of women and our role in the family and in society.

There are verses in the Qur’an that make clear the equality of men and women, like Chapter 33, verse 35 which says, “Indeed, the Muslim men and Muslim women, the believing men and believing women, the obedient men and obedient women, the truthful men and truthful women, the patient men and patient women, the humble men and humble women, the charitable men and charitable women, the fasting men and fasting women, the men who guard their private parts and the women who do so, and the men who remember Allah often and the women who do so – for them Allah has prepared forgiveness and a great reward.”

or Chapter 9 verse 71 and 72 “The believers, men and women, are protecting friends one of another; they promote the right and forbid the wrong, establish prayer, pay the poor-due, and they obey God and His messenger. As for these, God will have mercy on them. Surely God is Mighty, Wise. God has promised to believers, men and women, gardens under which rivers flow, to dwell therein, and beautiful mansions in gardens of everlasting bliss. But the greatest bliss is the good pleasure of God: that is the supreme felicity.”

or the story of creation in Chapter 7, verses 20-26 where Adam and Eve are discussed in Arabic’s dual voice which addresses them as a pair, as equal partners in sin, redemption and forgiveness.

There are verses that posit men and women in egalitarian familial relationships, such as Chapter 30, verse 21: “He created spouses for you from among yourselves that you might find comfort in them, and He put between you love and mercy. Surely these are signs in that for people who reflect.” The word used to describe the relationship — zauj — is an astonishing word, meaning both the pair as a unit, and each half of the pair in relation to one another. Perhaps even more amazing is that there is no bifurcation of masculine and feminine with this most intimate pairing of humankind. The Qur’an never refers to “zauj and zuuja” — husband and wife — in the Qur’an, rather both halve of this pair bond are referred to as zauj of one another. This stands in direct contrast to verses like the 33:35 above where all of life is differentiated by gender — from muslim and muslima, to mumin and mumina, and so on.

And one of the most beautiful descriptions of marriage, “you are a protecting garment for them and they are a protecting garment for you.” (2:187).

Even in mundane issues, the Qur’an provides us with a picture of egalitarian marriage, in Chapter 2, 233:, “(Divorced) mothers may nurse their children for two whole years, if they wish to complete the period of nursing; and it is incumbent upon him who has begotten the child to provide in a fair manner for their sustenance and clothing. No human being shall be burdened with more than he is well able to bear: neither shall a mother be made to suffer because of her child, nor, because of his child, he who has begotten it. And the same duty rests upon the heir. And if both parents decide, by mutual consent and counsel, upon weaning they will incur no sin [thereby]; and if you decide to entrust your children to foster-mothers, you will incur no sin provided you ensure, in a fair manner, the safety of the child which you are handing over. But remain conscious of God, and know that God sees all that you do.”

At the same time, there are verses in the Qur’an that create and perpetuate inequality. Perhaps the most infamous of these is Chapter 4, verse 34. “Men are the protectors and maintainers of women, because Allah has given the one more (strength) than the other, and because they support them from their means. Therefore the righteous women are devoutly obedient, and guard in (the husband’s) absence what Allah would have them guard. As to those women on whose part ye fear disloyalty and ill-conduct, admonish them (first), (Next), refuse to share their beds, (And last) beat them (lightly); but if they return to obedience, seek not against them Means (of annoyance): For Allah is Most High, great (above you all).”

Other verses reinforce this inequality, from Chapter 4, verse 11, that tells us, “Concerning the inheritance of your children, God enjoins [this] upon you: The male shall have the equal of two females’ share…” to Chapter 2, verse 282: “Call upon two of your men to act as witnesses; and if two men are not available, then a man and two women from among such as are acceptable to you as witnesses, so that if one of them should make a mistake, the other could remind her…” to Chapter 24, verses 30 and 31, “Tell the believing men to lower their gaze and to be mindful of their chastity: this will be most conducive to their purity – [and,] verily, God is aware of all that they do. And tell the believing women to lower their gaze and to be mindful of their chastity, and not to display their charms beyond what may be apparent thereof; hence, let them draw their scarves over their bosoms. And let them not display their charms to any but their husbands, or their fathers, or their husbands’ fathers, or their sons, or their husbands’ Sons, or their brothers, or their brothers’ sons, or their sisters’ sons, or their womenfolk, or those whom they rightfully possess, or such male attendants as are beyond all sexual desire, or children that are as yet unaware of women’s nakedness; and let them not swing their legs so as to draw attention to their hidden charms And O you believers – all of you – turn unto God in repentance, so that you might attain to a happy state!”

Perhaps most indicative of the disparity between men and women is the fact that all the people identified as prophets and messengers were male — from Adam down to Muhammad. There is debate about Maryam being a prophet, but even if you side with those who think she is, it is notable that sheis not identified as such by the Qur’an and she is the one prophet who does not preach, who does not deliver her message, but rather has her message delivered for her by her infant son, Jesus.

The Prophet’s life mirrors this dichotomy. On the one hand, his relationship with Khadija seems to be quite clearly a partnership of devoted equals, or even with her the more powerful of the two, given that she was older, wealthier, more socially connected, and his employer. On the other, we have his relationships with his subsequent wives, where he was polygamous with each having him only one day a week, or none at all, as Sauda gave her day to Aisha.

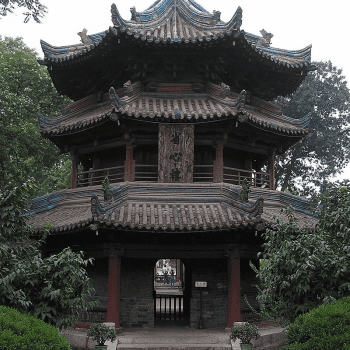

On the one hand, he praised women who were bold in seeking knowledge and parents who educated their daughters, on the other he set aside only one day a week for women to learn from him. On the one hand, he appointed Um Waraqa to lead prayers for a congregation that included men, and on the other, he segregated his own congregation (at least at times) with men in front and women in the back.

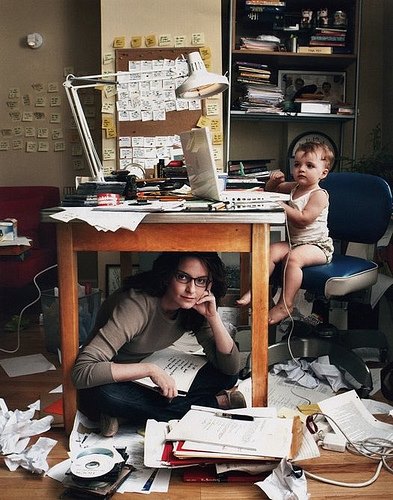

What are to make of these dichotomies in the Qur’an and in the life of the Prophet? As a feminist, I believe that these differing pictures of what means to be a man or a woman, what relationships look like, even what our roles in society are, enable us to make the choices that work for us. One of the central tenets of feminism is that each woman should have agency over her own life — that is, she has the right to choose her own life course, including how to formulate her relationships, to husband, to family, and to society. The breadth and depth of egalitarianism in the Qur’an empowers me as a feminist to live in an egalitarian marriage, to treat my children with dignity and respect more akin to that you extend to peers than to minors, to pursue my motherhood and my career and my interests with regard only for my own ambitions, desires and dreams. It also empowers someone who finds comfort and stability and self-expression in a more patriarchal relationship and a more patriarchal society to live as she sees fit, to pursue interests she deems appropriate and satisfying.

The variety of ways the Prophet arranged his mosques provides a precedent to those who find peace in a segregated space, and to those who wish to pray in complete equality, sharing leadership among the men and women in the congregation. So too social matters — amongst the women who went to the battlefield there were warrior and nurses, amongst the companions of the prophet were martyrs, and business women, and cooks, and scholars, and doctors, and… and… and… so many examples of so many different ways of leading good lives that we have a wealth of opportunity for self-fulfillment however we understand that.

In an ideal world, this could be accomplished without coercion, and without disparagement of different life choices. We clearly aren’t there yet. Perhaps the best, first step we can take to achieving is to live up to another precept in Islam — freedom of conscience — there is no compulsion in religion. (Chapter 2, verse 256). When governments do not try to impose one view of Islam on us all, and we do not try to impose them upon each other, only then we will be free to explore the significance the Qur’an has to our own lives and to live by its teachings in truly genuine ways.