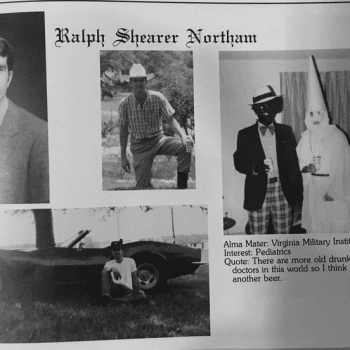

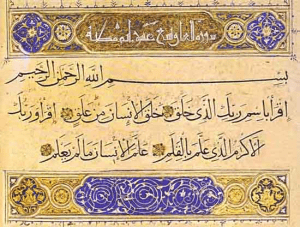

The story of the Qur’an begins in Ramadan, 610 AD. Muhammad, who was not yet the Prophet Muhammad, was in the habit of meditating in a cave high on the hillsides surrounding Mecca. On one such occasion, the angel Gabriel came to him and told him to read. Muhammad replied that he could not read. Gabriel pressed him tightly and then commanded him again to Read, and Muhammad again said that he could not read. Gabriel pressed him against, and said:

Read! In the name of your Lord who created:

He created man from a clinging drop.

Read! Your Lord is the Most Generous

Who taught by the pen,

Taught man what he did not know. (96:1-5)

These verses marked the beginning of revelation. Muhammad didn’t know what to make of what was happening to him. He ran down the mountain, his heart beating wildly. He was so terrified of the experience, that he asked his wife Khadija to cover him up. After he calmed down, he told her what had happened and confided that he was afraid for himself, unsure whether his experience was true or if he was going mad. Khadjia reassured him that nothing ill could come to him, as he was a good man, known for upholding the ties of kinship, speaking truthfully, helping the poor and destitute, serving his guests generously and assisting those who had stricken by calamity. She also took him to her uncle Waraqa, a Christian monk, who agreed that Muhammad was indeed become a Prophet.

The second revelation came a few weeks later,

You, wrapped in your cloak,

Arise and give warning!

Proclaim the greatness of your Lord;

Purify yourself;

Keep away from all defilement;

Do not be overwhelmed and weaken;

But be steadfast in your Lord’s cause. (74:107)

These verses may refer to what happened after the first revelation or they may refer to the fact that when Muhammad saw the angel Gabriel again, he ran home frightened and once more begged Khadija to cover him up again.

Either way, practically from the beginning of revelation we see that the Qur’an is a book rooted in history, responding to the Prophet’s thoughts and actions, reacting to happenings in his life. While it presents many eternal lessons, it is also speaking into a context, directed at a particular culture, and addressing the events occurring at the time.

Time and again, as we read through the Qur’an we are reminded of this fact. The beginning of Chapter 80 scolds Muhammad for paying attention to important people and rebuffing a blind old man who wanted to learn more about the religion he had recently embraced. Chapter 3 discusses the believers behavior during the battles of Badr and Uhud. Chapter 24 addresses those who slandered Aisha with accusations of adultery.

The commentary and explanations of the Qur’an that are currently popular almost exclusively focus on the eternal nature of the Qur’an, proclaiming that not only is its wisdom and spiritual guidance intended to uplift mankind forever, but that the individual rulings pertaining to the specific circumstances Muhammad encounter are also universal.

As a progressive Muslim, I question that approach to the Qur’an since the book is so clearly addressing a specific community in a specific historical context. I can’t help but think that the spiritual guidance, the general teachings about how to live a good life are eternal, but that the specifics of the rules would be different if the Qur’an was being revealed to a different culture or in a different time.

I mean, surely if the Qur’an came to today’s society, with our bent toward marital equality and our understanding of domestic violence, God wouldn’t advise spouses who aren’t getting along to resort to physical resolutions to disagreements? Surely in a society where familial bonds don’t extend much beyond the nuclear family, and men and women are both expected to be breadwinners, inheritance would be divided up more equally? And how about those draconian punishments for petty crimes? I have to think that things would be very different.

Ramadan brings this belief into sterling clarity for me. The verses about fasting times during Ramadan are unambiguous: “eat and drink until you can discern the white streak of dawn against the blackness of night.” (Surah Baqara, verse 160) Clearly, this verse is not universal. It does not take into consideration Muslims who live above the Arctic Circle where for several months of the year the sun never comes completely over the horizon, and other months it never sets, making fasting according to the rule impossible. Nor does it consider the impracticality of refraining from food and water when daytime lasts 18, 19 or more hours. The only possible conclusion is that that the injunctions about fasting times are meant specifically for the people of Mecca and Medinah, for their circumstances and situation, and were never intended to be rules for all places and times.

If this is true for something so fundamental as when and how to fast in Ramadan, a ritual that is one of the Pillars of Islam, how much more so for less consequential rules?

So what’s a modern Muslim to do? How do we know what is universal and good for all times and what applies specifically to Muhammad’s era? For starters, there are values in the Qur’an that are clearly universal – be mindful of God through worship; give freely in charity; be patient in the face of difficulties; stand for justice; speak honestly and bear true witness; uphold your obligations, contracts and oaths faithfully; keep ties with your kin; be kind to strangers and travelers; care for orphans and treat them well; uphold the brotherhood of all mankind; speak politely to others; count your blessings; use your brain to gain wisdom from the world around you and seek education; be modest in dress and speech; make peace whenever possible, etc. These principles always make good sense.

There are prohibitions that are also clearly universal. Don’t lie, steal, cheat, commit slander or murder, don’t think you’re better than anyone else because of your family, wealth, power, knowledge or prestige; don’t judge people for ways different than your own or for their shortcomings; don’t engage in casual or nonconsensual sex; don’t bear false witness; don’t cut off your family; don’t become rigid or go to extremes, especially in religion.

That leaves the rest of the Qur’an’s teachings. As a progressive Muslim, I believe we need to understand the Qur’an and its teaching through the lens of the history into which it was revealed. We may come away with the same understanding we have always had, or we may come up with something new. We may continue to believe particular verses are applicable universally. Or we may decide that God would want something different from us today than what was applicable in the 7th century.

For instance, the verses that tell us “Do not take the disbelievers as friends and protectors instead of the believers” (3:28, 4:144) means something quite different when you understand it as a universal law and when you understand within its historical context. When that verse was revealed, the non-Muslims of Mecca had enacted a systematic campaign of terror that resulted in many Muslims fleeing to Ethiopia, after which they banished the remaining Muslims from Mecca and refused to trade with them, confiscating their homes and possessions. And once the remaining Muslim community moved to Medina, they engaged in open warfare with the intention of wiping out the entire Muslim community. Of course, you wouldn’t extend your friendship and trust to people who were trying to eradicate your whole community!

Compare that today where multiculturalism is celebrated across the globe, and Muslims, Jews, Christians, Hindus, atheists, etc here in the west come together to feed poor people and build houses for the homeless, to support civil rights for all and struggle for a kinder, more just civilization. If the Qur’an had been revealed today, the exhortation might be “Do not take bigots and racists for friends over those who love all and do good works together.”

To be clear, I’m not talking about willy-nilly, picking over the Qur’an scooping up what you like and discarding what you don’t. I’m talking about, a systematic approach to understanding the Qur’an with reference to the events of the day and the milieu in which it was revealed and thus to understand not just the actual words, but also to grasp at the intention behind the verses, the intended outcomes, and to work to implement those in our own context and culture.

While this may seem like a huge departure from traditional theology and jurisprudence, the companions of the Prophet clearly saw the Qur’an and its teachings in this manner. For instance, Omar suspended punishments for theft mentioned in the Qur’an during a famine. Obviously, he understood that as circumstances change, so too should our understanding of the Qur’an. I am suggesting nothing more and nothing less.