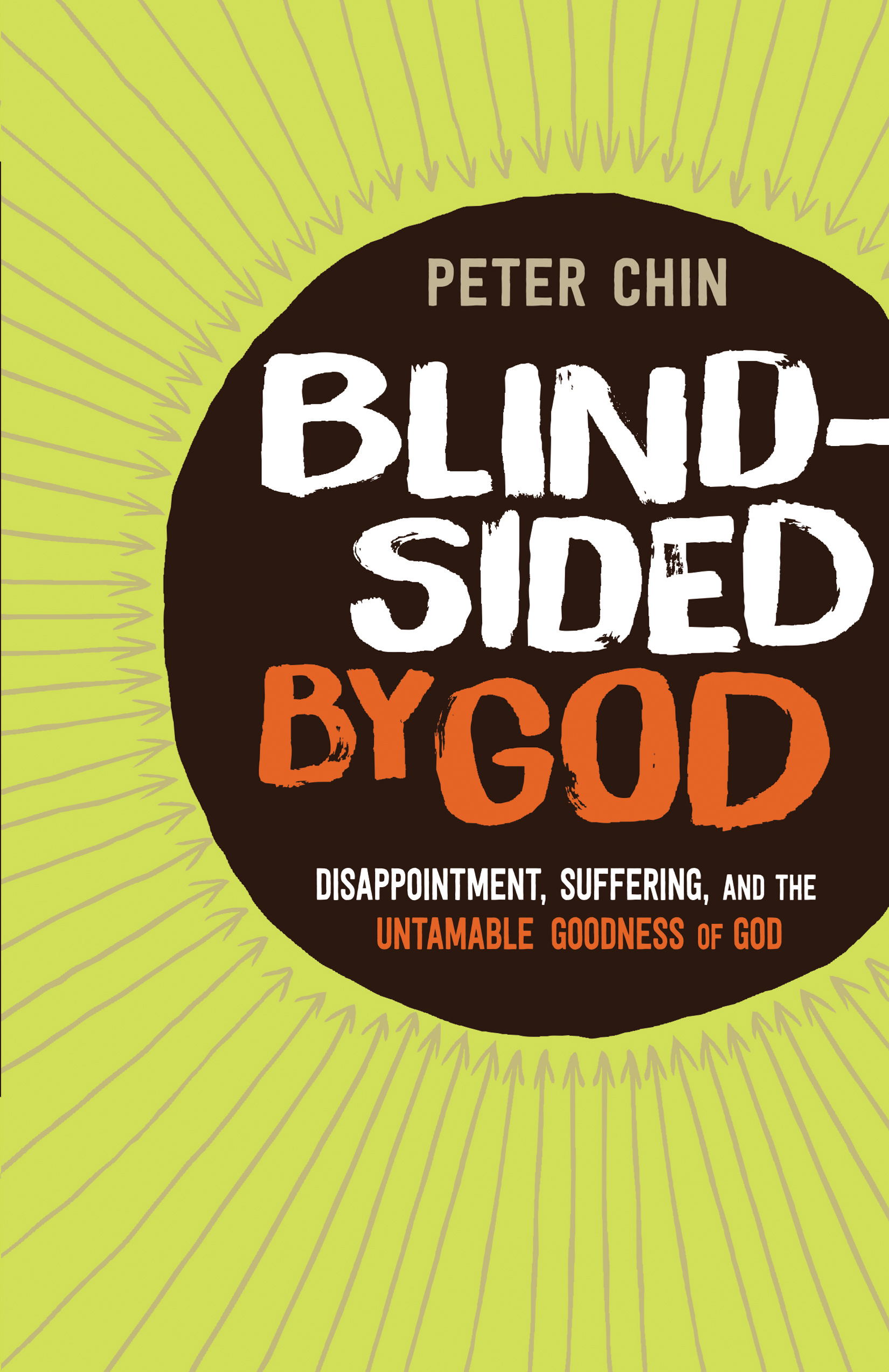

Peter Chin has written a book entitled Blindsided by God. In it, Chin explores the reality of suffering, the mystery of God’s ways, and why, even in the darkest times, there’s always reason for hope.

I caught up with Peter recently to discuss his new book. Enjoy!

Instead of asking, “What is your book about,” I’m going to ask the question that’s behind that question. And that unspoken question is, “How are readers going to benefit from reading your book?”

Peter Chin: That really depends on the context of the reader. For those who are doing pretty well in life but are simply looking for an interesting read, the book will definitely provide that. It is a remarkable true story, one filled with as many twists and turns as you would find in any work of fiction.

But the book was really written with a more specific audience in mind. I wrote the book for those who find themselves in an especially difficult season of life, where they have experienced loss or disappointment. For those who find themselves in that context, this book will help them to remember something precious – that they are not alone in their pain. This in itself is an important realization, and a powerful source of encouragement.

But this book also provides another precious and scarce resource, which is hope. Although the book is very open about the grim reality of suffering, it is ultimately a story of hope and new life, a story where in the midst of hopeless circumstances, God does something truly miraculous. I pray that those who read the book will be reminded that God is still present in their lives, even when it seems like everything testifies to the opposite.

Explain the title. What does it mean to be blind-sided by God?

Peter Chin: The title has a dual meaning. Usually when a person says that they have been “blindsided by God,” they mean that in a negative sense—that they are struggling to understand why God would let something terrible and painful take place in their lives. During those seasons, we find ourselves repeatedly asking that most human and pressing of questions: “God, if you love me, why are you letting these things happen to me or the ones that I love?” This is partly what it means to be blindsided by God, and is what the first half of the book describes.

But I also intended this phrase to be used in a more positive sense as well. In the second half of the book I would be blindsided by God, but in a very different way. I would discover that God is far different from how I imagined him: larger, stranger, but more wise and loving than I had ever thought he could be. By the end of our story, I would be again blindsided by God, but in the opposite sense – I would be blindsided by his love and untamable goodness. And this is what I truly mean by that title.

Tell us a bit about the experiences that shaped the insights in the book.

Although theological in nature and in perspective, the insights of this book were directly shaped by the actual events that my wife and I went through: my wife’s miscarriage and cancer diagnosis, the termination of our insurance, and finally, discovering that she was pregnant with our third child while she was being prepared for her mastectomy. The benefit of this is that these are not simply thoughts I had while sitting at a coffee shop, pondering the meaning of life. These are thoughts that came to me while sitting next to my wife during her chemotherapy treatments. The lessons in this book are not philosophical meanderings. They are insights that were birthed out of painful real-life experience.

How is your book different from the other books on suffering, trauma, and understanding God’s sovereignty in the midst of pain?

Peter Chin: This book is not an intellectual treatise on suffering, although thoughts and insights on that topic definitely are found throughout the book. It is ultimately a story, and the beauty of story is that it is far easier to see ourselves in the narrative of another, and in that process, make sense of our own situation in turn. We are far more likely to listen to a person if we feel that they understand our own experiences.

But it is not simply a story of suffering and disappointment, as helpful and important as it is to share such narratives. It is also a story of how God revealed to me that although he was mysterious and wild, he was also good and loving. It is a story that openly acknowledges the reality of suffering and pain, while affirming God’s goodness in the midst of that pain. And it is important to acknowledge both of these truths, which is precisely what our story does.

The other reason that this book stands out from others is that the events described within are wide-ranging and universal to the human experience. In it, I talk about being dumped by my future wife, experiencing a miscarriage and a break-in, a cancer diagnosis, and even feeling like a failure as a pastor and church planter. This may be my personal story, but at the same time, it is one that I feel many can relate to.

Give us two or three insights from the book that would be helpful to Christians who are suffering and don’t understand why God hasn’t yet intervened in their situation.

Peter Chin: One lesson I learned in my own journey is that part of the reason I felt so betrayed by God was that my theology had been subverted by popular culture. Despite my seminary education, I still felt like things like this should not happen to those who follow after God, that if you follow after God, you should expect some measure of protection from the worst that the world has to offer. But 1 Peter 4:12 clearly tells us that we should not be surprised by trials. And we can see in both the lives of Jesus and the disciples that people can follow God very closely and still suffer quite deeply.

It was through this that I realized that my theology was not as biblical as I had believed, but had been tainted by the world’s understanding of blessing. And it was suffering that exposed this difficult truth. In order for a better understanding of God to be built in my life, this old and marred one had to be torn down first. I suspect that this is the case for more than a few of us, that part of the reason we are so surprised by negative situations is that we don’t realize how much we buy into the gospel of the American dream rather than the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Another insight I provide in the book is that suffering and blessing often co-exist in life. We often take a very binary approach to life, where either we are doing well or we are doing terribly, but never both at the same time. And because this is so often our approach to life, we fail to see God in the difficult times, or else fail to acknowledge the hurts of others in the good times. But the truth is that suffering and blessing often co-exist in the same season. In fact, the co-existence of suffering and blessing makes our blessings all the more pronounced. Pain provides a darker backdrop against which the daily providence of God becomes far more visible. After all, it’s only at night that you can see the stars.

Jesus said that Satan is the one who kills, steals, and destroys. James says, “Resist the devil and he will flee from you.” Based upon texts like these, some argue that suffering, pain, and tragedy are not authored by God, but by the devil, so Christians should resist and stand against such things. Others say that everything, including the evil, pain, and suffering that befalls believers, is authored and initiated by a sovereign God, so we should embrace and accept such things. What do you have to say about this debate?

Peter Chin: I believe that the answer lies somewhere in the middle. No, I don’t think that God authors pain, tragedy, and suffering. These realities are not a product of God but a product of sin. We were not created to be in pain, or to be separated from God, or to die. All of these states were a consequence of our sin. If God were the one who was primarily responsible for the terrible suffering that we witness and experience in the world, few of us would want to follow him.

But at the same time, although God does not author that suffering, he does allow it. That might seem like an insignificant distinction, but it is not. He allows suffering because he is able to use it for our good. His sovereignty is such that he is able to wield suffering and tragedy as his tools, to work all things for the good of those who love him, to refine us and to build our character.

Some might ask why a loving God would ever permit suffering, but the fact is that this is not as rare a dynamic as one would think. Our own parents would permit us to suffer at times—getting fillings in our teeth or bringing us to the doctor or hospital for a shot, or even major surgery—not because they do not love us, but because they do. A good parent knows in their wisdom and love that these experiences, as painful as they might be, can be used for greater good. And so it is with God, who is an even wiser and more loving parent than any earthly parent.

What else would you like to say about the book?

Peter Chin: One final aspect of the book is that many of the stories are told from a humorous and self-deprecating perspective. I didn’t do this to minimize the difficulty of human pain, nor because I was ignorant to our situation. I consciously injected humor into my account as a way to suggest that humor is one of the best means by which we deal with suffering in our lives. It has a way of taking our eyes off our pain, even for a moment, which is no small blessing. But laughter also serves another purpose during seasons of difficulty, in that it reminds us, like I said earlier, that good and bad often co-exist in our lives, tears and laughter both. We needn’t feel ashamed for weeping during tough seasons, but neither should we feel bad if we crack a smile.