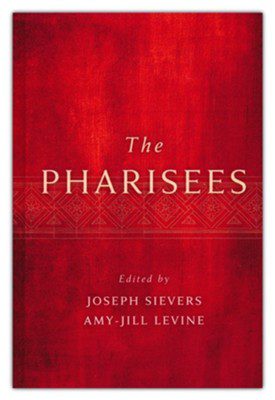

The Pharisees is a new 500-page book edited by Joseph Sievers and Amy-Jill Levine.

Note that scholars disagree regarding the specific relationship that the Pharisees had with Jesus in the New Testament as well as their overall disposition. This book favors certain perspectives. And it does a great job in that endeavor.

I caught up with the editors to ask them some questions about their robust new volume.

Enjoy!

What provoked you to write this book and how does it differ from the other books in print on Pharisees?

The book is an edited collection with contributions from an international gathering of both Jewish and Christian scholars who work in New Testament Studies, the Dead Sea Scrolls, Josephus the Jewish historian, rabbinic Judaism, medieval and modern Jewish and Christian thought, history, and art, contemporary films and textbooks, preaching, and theology.

The idea for the conference grew out of the realization that serious interdisciplinary work concerning the Pharisees was needed. It had to include Jewish and Christian representatives of all these disciplines. Only in this way we could confront and try to effectively rectify prejudices and stereotypes.

What was it specifically about the Pharisees that caused Jesus to have so much trouble with them?

Jesus, the Pharisees, and various other individuals and groups had different ways of understanding the Torah (we might compare various Christian groups today who have different ways of understanding what Paul teaches about women or slaves, or different ways of understanding what the Gospels suggest concerning relationships with outsiders).

Jesus and the Pharisees share much in common: they are among the people rather than out in the desert, they are both known for their piety and simplicity, they both have the attention of the crowds. The closer people are, the more difficult the process of self-definition.

Many scholars believe that the book of Acts is a work of historiography. What does that mean exactly?

The evangelist we call “Luke,” who wrote both the Gospel and Acts of the Apostles, wrote history the way other historians of the time wrote history: they were less interested in recording facts than in promoting a certain way of life and a certain set of values for their readers.

Luke freely edited his sources (including among others the Gospel of Mark), crafted speeches that he found appropriate for specific occasions, and corrected what he found to be certain misperceptions that other followers of Jesus held. That is why he tells us, in the Prologue to the Gospel, that while others have attempted to tell the story of Jesus, he is going to present what he considers the correct version.

Where did the Pharisees come from? What is their origin as a party?

We do not know. Josephus first mentions them following the Maccabean revolt about 150 BCE. They are a lay group rather than part of the priesthood, they appear to have started as a political party involved with local politics while Judea was ruled by fellow Jews, but after Rome gained control in 63 BCE and subsequently established client rulers in Galilee and, in 6 CE, a Roman governor in Judea, they appear less interested in politics and more interested in promoting piety among the people.

What were the main differences between the Pharisees and the Sadducees?

- Pharisees believed in a combination of fate and free will; Sadducees believed only in free will.

- Pharisees believed in resurrection of the dead; Sadducees did not (or, at least they did not believe one could locate the teaching of resurrection of the dead in Torah)

- Pharisees had the “tradition of the elders” through which they understood how to interpret Torah; Sadducees did not, or followed different traditions.

- Pharisees are in both Judea and Galilee and are popular among the masses; Sadducees tend to be based in Jerusalem and, according to Josephus, lacked popular support.

- Pharisees were interested in extending priestly sanctity found in the Temple to all Jews; Sadducees were more interested in retaining priestly privilege and responsibility.

Who was wealthier in Jesus’ day and who owned more land?

The high priesthood based in Jerusalem had land holdings. However, the “elites” or the “rich” are primarily the “sinners and tax collectors” with whom Jesus affiliates. This affiliation is one of the reasons the Pharisees question his table companionship.

The issue is not dietary regulations. The issue is Jesus’s associating with the ancient equivalents of drug dealers, loan sharks, and contract killers.

Which party was more popular with the Jewish people?

Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, complains that the people follow the teachings of the Pharisees; he, a priest, thinks they should be listening to the priests instead.

What was the synagogue ruler called?

The Greek is archisynagogos which is literally, “The head” or “the first” of the synagogue. The position was probably like that of a patron. We also have inscriptions that use the feminine form of the term, which means that women also held this position.

What was a “rabbi” in the first century exactly (before A.D. 70)?

At the time of Jesus, “rabbi” is simply a polite title with the connotation of “teacher.” Anyone could be a rabbi, since the position is voluntary. Not everyone could be a priest, since priesthood is inherited (on the paternal line). “Rabbi” is, at the time of Jesus, a title of respect, with the connotation of “teacher.”

Could any visitor speak in a synagogue?

Synagogues are public spaces where anyone could speak. Gentiles attended synagogues and some even built synagogues and served as patrons of synagogues (see Luke 7.1-10). We see in Luke 13.13 a woman speaking in a synagogue.

If someone reads your book to the end, what are the big takeaways you want them to have from reading? What would you like them to understand and remember, exactly?

As Pope Francis states in the final section of the book, it would be helpful for Christians to stop using the Pharisees as negative foils and to see how close Jesus and the Pharisees were on the basics, such as love of G-d (Deuteronomy 6) and love of neighbor (Leviticus 19).

They may come to see Paul not as rejecting his Pharisaic training but as, in his view, becoming a better Pharisee following his Damascus Road experience.

We can better appreciate the Pharisees Nicodemus in the Gospel of John and Gamaliel in the book of Acts. In locating the Pharisees in history, including their connection to rabbinic Judaism, we can have greater respect for how they interpreted scripture in a way that welcomed everyone, showed people various ways of sanctifying daily life, provided guidance on how to resist assimilation into the broader Roman Empire, and modeled debate over how best to live according to divine will.

By recognizing how they have maligned the Pharisees over the past 2,000 years, Christians can correct past misinterpretations and use this new and compelling study to stop bearing false witness against Jews past and present. By seeing how Pharisees are portrayed in the ancient sources, Jews can get a better sense of their own history and be in a better position to respond to Christian misunderstandings.

Thank you!