As I continue early preparation for the book on the teaching life that I hope to write during my upcoming Fall semester sabbatical, I find myself considering many of the misconceptions that people outside of academia have concerning professors. One of these misconceptions, one that has become more and more prevalent over the past decade or two, is that although they present themselves as “experts,” academics are generally far more impressed with their knowledge and expertise than they should be. Let me start with allowing that I know a few academics for which this description is dead-on accurate. But as is usually the case, there is a lot more going on than the stereotype presents.

Once around twenty-five years ago, while a still untenured member of the philosophy department at my college, I participated in a symposium on the late Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason) which had been released the previous year. The symposium was a shared event between the philosophy and theology departments. One member from each department would present a twenty-minute paper, and a panel of four philosophers and theologians would present brief comments. Sounds like a lot of fun, huh? The original presenters would have a chance for response, then the whole thing would be turned over to the audience for questions and interaction.

I was assigned to present the longer paper for the philosophy department. In the paper I did what philosophers do—I raised what I considered to be some critical problems with the encyclical, suggesting that the Pope might even have gotten some important things wrong—for instance his conclusion that reason must always submit to the authority of faith when they are in conflict. I knew from the start, of course, that this might be a bit controversial at a Catholic college—I was right.

The audience that evening was impressive in size, exceeding what I’ve seen for any academic event in subsequent years at the college until last semester’s discussion of the abortion issue for which I was a panelist. The larger community, particularly the parishioners of St. Pius V church across the street, had been invited and came in droves, expecting I’m sure to hear a cheerleading love-fest for their beloved Pope. Instead they got me raining on their parade. A colleague reported afterwards that one woman in the back row complained during the paper to her neighbor in an audible stage whisper: “I can’t believe they let people like him teach here!”

Rumblings during my paper exploded into direct challenge during the Q and A. After defending and clarifying my position—pretty well, I thought—for a few minutes, an exasperated older gentleman in the front row asked “Dr. Morgan, is there no place in philosophy for humility?” I responded, honestly but perhaps a bit uncharitably, with a guffaw of laughter (if introverts ever guffaw). “The longer I do philosophy, the more I realize how much I don’t know!” Twenty-five years later, I am even more convinced of what I don’t know and of the importance of humility in the teaching profession.

Still, I didn’t spend nine years in college earning three degrees culminating in a Ph.D. in philosophy to simply be humble about what I have learned and what I know. I actually get a bit testy when someone commenting on this blog, as has happened many times, tells me in no uncertain terms that my training as a philosopher and experience as a philosophy professor actually makes me less qualified to say anything definitive within the realm of philosophy than what they came up with last evening in conversation with their buddies over a few joints and beers. How exactly should humility and expertise temper each other?

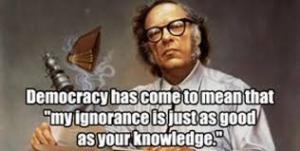

More than four decades ago, at the dawn of the Reagan era, the late Isaac Asimov wrote that

There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.”

Sadly, it has gotten worse since Asimov wrote this. As an academic and a college professor, I find myself at the crossroads of expertise and common knowledge on a daily basis. Consider a recent example of an academic asked to provide publicly her expert analysis of an important issue.

You might remember a House Judiciary Committee hearing in December 2019 that was an early part of the hearings that resulted in the first impeachment of then President Donald Trump. The witnesses at the hearing were four academic, legal experts on all matters concerning impeachment. One of the witnesses was Stanford law professor Pamela Karlan. There was something about Professor Karlan that some found so off-putting that they just had to bloviate about it. Here’s a representative reaction to Professor Karlan from “Fox and Friends” the morning after the hearing:

The disdain is evident, and, you know, it sort of recalls back to the 2016 election when voters didn’t feel heard, when they resonated with President Trump, because there is this elitist, disdainful reproachment coming from the far left, and especially in academia, that makes people feel disconnected and undercut. Everything about her exuded that she was better, and smarter, than anyone watching. And that’s so off-putting.

Now that just pisses me off.

It pisses me off for many reasons, but primarily because the quote from “Fox and Friends” exhibits a whole bunch of lame stereotypes about academics, stereotypes that anyone whose life is spent in academia (as mine has been for more than three decades) quickly becomes so sick of that they want to vomit. After seeing the clip quoted above on Twitter, I responded with this:

I’ve been a college professor for 30 years. I’m used to being in a room where everyone believes they are the smartest person there. And they very well may be. Half the people at monthly department meetings in my department of twenty faculty have confidence that could seem like disdain (but isn’t). Deal with it.

As I read my tweet now, more than three years later, I realize that it is far more measured than I was feeling at the time.

Over the past two decades I have been both a department chair and the director of a large interdisciplinary academic program that, at any given time, involved at least seventy-five faculty and 1800+ students. People often used to suggest that trying to direct faculty must be like “herding cats.” I always responded that it’s worse. It’s like herding cats when each of the cats in the room has a Ph.D. and is sure that she or he is the smartest cat in the room.

My guess is that during the December 2019 hearing, Dr. Karlan was in academic “professor and expert” mode; that is, after all, why she was asked, along with her three expert colleagues to be there. A highly educated and trained scholar with relevant expertise—in this case, expertise in legal and interpretive matters concerning impeachment—was asked to respond to questions relying on her training and expertise. She did, directly and pointedly. And then she is criticized for acting and sounding like the very expert and highly trained person that caused her to be summoned to the hearing in the first place.

My guess is that during the December 2019 hearing, Dr. Karlan was in academic “professor and expert” mode; that is, after all, why she was asked, along with her three expert colleagues to be there. A highly educated and trained scholar with relevant expertise—in this case, expertise in legal and interpretive matters concerning impeachment—was asked to respond to questions relying on her training and expertise. She did, directly and pointedly. And then she is criticized for acting and sounding like the very expert and highly trained person that caused her to be summoned to the hearing in the first place.

Any academic or college professor could provide you with multiple examples of the same dynamic. “Please provide us with your expertise and knowledge, but please don’t do it in such a way that makes us feel that you have more knowledge or expertise than we do. Otherwise we might decide that you are an elitist and that you think that you are better than we are.” News flash, people. Dr. Karlan did know more about the topic under consideration at the hearing than you do.

That’s what being an “expert” on something means. The fact that she communicated her knowledge and expertise in a manner that you find “elitist” is your problem, not hers. Your ignorance is not just as good as her knowledge. If you are threatened or annoyed when you find out that some people know more than you on any number of subjects, that’s on you, not them. There is a difference between elitism and knowing what the f__k you are talking about.

To quote a phrase from 24/7 news channel talking heads that is vastly overused, “let me be perfectly clear.” If you got the impression, “Fox and Friends” person, from Professor Kaplan’s testimony that she thinks she is “smarter” than you, that’s because concerning the matters on which she was speaking, she is smarter than you. And me. And probably all but a couple hundred or so human beings on the planet. That’s why she’s an “expert.” She’s earned the right to deliver her insights with an authority and air that might cause you to surmise that she thinks she’s better than you. That’s because in this case she is better than you. Her opinion matters more than yours. That’s why the Judiciary committee wanted to speak to her and not to you. In this case, your opinion doesn’t matter. But her knowledge does.

This, of course, provides no formula for balancing humility with expertise, just as there is no formula for any part of work/life balance. But do me—and everyone else who in some part of their life has earned a certain amount of expertise—a favor. The next time someone speaks from within the expertise that they have gained through education and/or experience, give them the benefit of a doubt, even if what they are saying is contrary to what you think or want to believe. They probably know more than you and I do on the topic. Imagine that.