The Gospel reading for last Sunday, the First Sunday of Lent, is the account of Jesus’ forty days of temptation in the wilderness from one of the synoptic Gospels. The account du jour was from Mark’s gospel, which–as usual–was brief, to the point, and lacking in some detiails (such as the actual content of the three temptations). The story of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness is also the centerpiece of one of the greatest passages in all of literature, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s tale of the Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov. What if, the Inquisitor asks, Jesus had succumbed to one of the temptations? Wouldn’t things have been better in the long run?

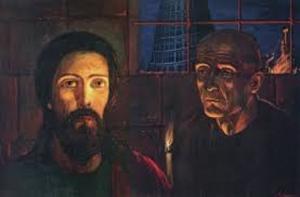

Imagine that Jesus unexpectedly shows up in sixteenth-century Seville during the height of the Spanish Inquisition. Although “He appeared quietly, inconspicuously,” everyone recognizes him and immediately starts bringing those who are sick and disabled to be healed. The Grand Inquisitor, an old and severe man “almost ninety . . . with a gaunt face and sunken eyes from which a glitter shines like a fiery spark” watches from the sidelines. When Jesus raises a young girl from the dead as her funeral procession passes by, the Inquisitor has had enough. He motions to his guards, the crowd parts, and Jesus is taken into custody.

What follows is an extraordinary monologue in which the Inquisitor rails against a silent Jesus for having returned to mess up everything that future generations of his claimed followers have accomplished in the fifteen hundred years since Jesus’ ascension. From the perspective of the Church which the Inquisitor represents, Jesus’ original message that human beings have the freedom to choose to follow and be in relationship with God was both elitist and misguided.

As it turns out, the Inquisitor argues, the vast majority of human beings do not want to be free. Rather, they will predictably turn their freedom over to the nearest authority who promises security and safety in exchange for that freedom. Jesus’ message, in other words, is based on a misreading of human nature. We are by nature too weak to handle freedom and the responsibility that goes with it. All we really want is for someone to take care of us.

The Inquisitor uses the three temptations as described in Luke’s gospel to frame his monologue. In his estimation, the three challenges thrown by the devil at Jesus “express in three words, in three human phrases only, the entire future history of the world and mankind.”

The Inquisitor uses the three temptations as described in Luke’s gospel to frame his monologue. In his estimation, the three challenges thrown by the devil at Jesus “express in three words, in three human phrases only, the entire future history of the world and mankind.”

Do you think that all the combined wisdom of the earth could think up anything faintly resembling in force and depth these three questions that were actually presented to you then by the powerful and intelligent spirit in the wilderness?

Consider, for instance, what really is contained in the first temptation, which the Inquisitor expansively rephrases as follows:

You want to go into the world, and you are going empty-handed, with some promise of freedom, which they in their simplicity and innate lawlessness cannot even comprehend, which they dread and fear . . . But do you see these stones? Turn them into bread and mankind will run after you like sheep, grateful and obedient.

The Inquisitor fully understands that obedience bought with bread is not obedience freely given, but so what? Human beings are not only incapable of handling freedom, but they also don’t want it in the first place.

Man has no more tormenting care than to find someone to whom he can hand over as quickly as possible that gift of freedom with which the miserable creature is born.

What do human beings want more, freedom or security? Choice or to be taken care of? I often frame this question with my students by telling a story from the month after 9/11, before any of them were born. I was scheduled to present a paper at an academic conference in October 2001 in Fort Lauderdale, Florida; my paper had been accepted for presentation several months prior to the devastating events of 9/11/01. Now, six weeks or so after that devastating day, Jeanne and I had to decide whether to fly from Providence to Fort Lauderdale in a world that seemed far from safe. We chose to do so, although as it turned out close to half of the conference’s scheduled presenters chose otherwise.

At the airport in Providence, and particularly at the larger Fort Lauderdale airport, security was tighter than we had ever seen. Lines snaked out the front doors of the terminal; it took three or four hours to make it through security. Throughout the terminals were dozens of military personnel armed to the teeth and ready to act. Americans had seen things like this on television from other countries, but now it had come to our doorsteps. Given the general impatience and entitlement of Americans, it was remarkable that we heard not a single complaint. Rather, would-be-travelers thanked the soldiers for their service and for “keeping us safe.” Our freedoms were significantly restricted and hindered those days in the interest of perceived security, and no one complained. Everyone was thankful.

“Many of you are flying home or somewhere with a beach for Spring Break soon,” I said to my students. “What would your reaction be if you had to wait three or four hours to get through security?” “I’d be pissed!” one said. “People would be very upset!” another imagined. Why? What’s the difference between the compliant airport crowd two decades ago and the imagined angry crowd today? After 9/11, we were willing to give up a lot of our freedoms in exchange for perceived security. Because there has not been another 9/11-style terrorist attack on American soil since then, we now feel secure enough to insist on as unlimited freedom as possible. Until we start feeling unsafe again, that is.

Jesus’ answer to the devil’s first temptation, of course, is “man does not live by bread alone.” There are more important things, in other words, than having your needs taken care of and feeling secure. Freedom, for instance. “My, my,” the Inquisitor responds. Who would have thought that the Son of God could have misread human nature so badly?

You objected that man does not live by bread alone, but do you know that in the name of this very earthly bread, the spirit of the earth will rise against you and fight with you and defeat you, and everyone will follow him exclaiming, “Who can compare to this beast, for he has given us fire from heaven!” . . . Feed them first, then ask virtue of them.

According to the Inquisitor, the work of religious authorities for the past fifteen centuries (and arguably for the next six since the Inquisitor) has been to reshape and retool Jesus’ message into something more in tune with what human beings actually are rather than some hopeful and stylized vision of what they might be. The Inquisitor tells Jesus that.

Had you accepted the “loaves,” you would have answered the universal and everlasting anguish of man as an individual being . . . namely “before whom shall I bow down?” There is no more ceaseless or tormenting care for man, as long as he remains free, than to find someone to bow down to as soon as possible.

The Inquisitor provides a powerful challenge that raises important questions for every person who claims to be a follower of Jesus. Do I truly understand how radical and challenging the call of the gospel is? Am I really capable of accepting the responsibility that goes along with freely seeking to live out a life of faith in real time? Wouldn’t it be much better simply to turn that freedom and accompanying responsibility over to someone or something else—a church, a political party, an authority figure, or a social construct that will break the life of faith down into manageable proportions in exchange for my obedience and submission to their demands? Ultimately, what am I looking for? Freedom or security? Radical open-endedness or certainty? Risk or safety?

From his prison cell just weeks before his execution by the Nazis, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote that, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” That’s the sort of thing that the Grand Inquisitor says is far too demanding and difficult for human beings. Was he right?