Last week I introduced a bunch of honors sophomores to Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s distinction between “Cheap grace” and “Costly grace,” the difference between committing verbally to one’s faith while allowing it to affect one’s life only on the surface level (cheap), and embracing the life-changing and completely disruptive things that will happen if one takes one’s faith seriously (costly). I likened the distinction to the difference between light beer and real beer. Light beer smells like and looks like beer, but upon taking one taste one will say “that isn’t real beer!” (not a comparison that should work with 19-20 year olds, but it does). Neither is cheap grace the real thing.

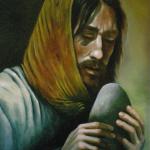

![olivyaz-john_6_68[1]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/09/olivyaz-john_6_681.png?w=300) In the Gospel of John, a number of Jesus’ followers complain after one of his teachings that “this is a hard saying; who can understand it?” When Jesus responds with a few more of his patented cryptic remarks, the writer tells us that “from that time many of His disciples went back and walked with Him no more.” These are not just hangers-on or fringe bystanders, looking to be entertained by another miracle. They are disciples, people who have been following Jesus for some time and have been witnesses to and recipients of the vast range of what the man has to offer. And they’ve had enough.

In the Gospel of John, a number of Jesus’ followers complain after one of his teachings that “this is a hard saying; who can understand it?” When Jesus responds with a few more of his patented cryptic remarks, the writer tells us that “from that time many of His disciples went back and walked with Him no more.” These are not just hangers-on or fringe bystanders, looking to be entertained by another miracle. They are disciples, people who have been following Jesus for some time and have been witnesses to and recipients of the vast range of what the man has to offer. And they’ve had enough.

These frustrated former disciples have a point. I might have gone with them. The sermon that causes them to finally fold up shop and go home is indeed a difficult one, wrapping up with the claim that only those who drink Jesus’ blood and eat his flesh will have eternal life. But this is by no means the only “hard saying” that they’ve heard from Jesus. From selling all you have being a prerequisite for following him, and letting your enemy smack both sides of your face while giving him your sweater to go with the coat he stole, to letting the dead bury the dead and hating your father and mother if you want to be his disciple, Jesus is full of “hard sayings.”

Consider, for instance, today’s gospel reading from Mark’s gospel where Jesus invites those who really want to follow him to “take up your cross and follow me,” observing further that those who want to save their lives will lose it, but those who lose their life for his sake will find it. And have a nice day.

Small wonder that Christians generally, lacking the guts to simply walk away, tend to water down and systematize the radical elements of the gospel into manageable directives. These reduced commands require behaviors and commitments that, although burdensome at times, can be carried out by any reasonably dedicated and sincere adult. For many of us, “this is a hard saying—who can understand it?” is not really a question of understanding at all. For we understand the hard sayings all too well, and conclude that they are just too much.

In October of 2006, the news of a shooting in an Amish schoolhouse in Nickel Mines, PA burst onto the nightly news. A neighborhood milkman carrying a small arsenal of weapons walked into the school and started shooting, killing five and wounding many more before turning his gun on himself and committing suicide. In the midst of deep grief, the interconnectedness of the Amish community was demonstrated through comprehensive mutual support and, most shockingly, immediate forgiveness.

At a prayer service the night after the shootings, the Rev. Dwight Lefever of Living Faith Church of God said that earlier in the day he was in the kitchen of the shooter’s family home when an Amish neighbor came by. “He wrapped his arms around Charlie’s dad for an hour,” Lefever reported. “He said, ‘We will forgive you.’” The pastor’s conclusion: “God met us in that kitchen.”

For several years I included this tragic event and its aftermath as the central part of the midterm exam in my General Ethics class. I provide my students with a newspaper account of the Amish community’s reaction to the shootings![images[7]](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/766/2012/09/images72.jpg) , and then ask them to try to make sense of what happened, particularly of the immediate forgiveness offered to the shooter’s family, within the structures of the moral frameworks we have studied during the first half of the semester. They can’t do it.

, and then ask them to try to make sense of what happened, particularly of the immediate forgiveness offered to the shooter’s family, within the structures of the moral frameworks we have studied during the first half of the semester. They can’t do it.

Furthermore, many of my mostly parochial-school educated students find something twisted, even offensive, in the willingness of the Amish community to forgive the murderer of their children. Comments range from “this is completely abnormal” to “these people are sick.” Over several semesters of this assignment, no student has yet commented favorably on a quote from a member of the Amish community included in the article: “Our faith tells us to act like Christ did on his way to the cross.”

Once shortly after reading my midterms I was drinking a beer (not a lite one) with a colleague at the local watering hole on Friday afternoon, unwinding from the week. I described the reactions of my students to the behavior of the Amish, reactions that were still fresh in my mind. In response, he said “I also am shocked by what the Amish did, but I don’t know why. As a Christian, I should be shocked that I’m shocked. They are just trying to do what Jesus said to do.”

Perhaps I can excuse my 19-20 year old students for being unable to find a place for radical forgiveness in their moral worldviews, which have been heavily influenced not only by strong family connections but also by a culture of the self and Christianity on the cheap. But what about me, someone significantly older and more experienced than my students?

As someone who has grappled with issues of Christian faith from my youth, my own temptation is to think of the Amish as über-Christians, somehow capable of moral heroics that normal persons such as I can only admire from a distance and not even aspire to. That rationale is particularly tempting because I, as many mainstream Christians, have been encouraged to think that it is the priests, pastors, monks, nuns, and missionaries who are the elite corps of Christians, freeing me to reduce expectations considerably.

But there is nothing in the Gospels to justify that easy out. Jesus’ call to take up my cross and follow him does not contain a loophole or room for an amendment. Which brings me back to the beginning—“this is a hard saying.” Jesus apparently demands everything of me, which is far more than I am willing to give. I can’t love my neighbor as myself. I can’t love God more than I love Jeanne. I can’t sell all that I have, give the proceeds to the poor, and follow Jesus. It’s too hard, and I’ve grown tired of pretending that a lukewarm, watered-down version is sufficient. Maybe I’m one of those who identify with the remaining disciples who asked, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.” So, where does that leave me? I want to follow. I can’t follow.

A still small voice offers a bit of hope. “Of course it’s too hard. Of course you can’t do any of these things. That’s the point. I can, and I am in you.” If divine love has indeed overcome the world, then perhaps it can even overcome me.