My wife Jeanne and I have been enjoying “The Chosen,” a multi-year cinematic life of Jesus that just released the fourth episode of its second season. I’ve seen on Facebook that its creators have been getting lots of raves, but also some serious pushback from conservative Christian elements. I have not made a study of these comments (which would require far too much time on social media), but the gist of those I’ve seen is that “The Chosen” is to be condemned because (gasp!) it does a masterful job of presenting Jesus as a human being. With a sense of humor, a spark of temper at times, occasional weariness, a few eyerolls to the camera in reaction to the frequent cluelessness of his entourage, and a learning curve of his own as he grows into the role he has been sent to play, “The Chosen’s” portrayal is the most compelling presentation of Jesus that I’ve ever seen.

And I’ve seen just about all of the portrayals in cinema and on television in the six-plus decades that I’ve been alive. In the world I grew up in, we were thoroughly familiar with all of the “Jesus movies,” if for no other reason than to sit back like Statler and Waldorf on “The Muppet Show” and say things like “That’s not scriptural!” and “The Bible doesn’t say that ever happened!” For those who are concerned about such things, although “The Chosen” takes advantage of its slower pace to develop relationships and story lines far beyond the outlines provided in the Gospels, I have yet to see anything that is contrary to the Gospels. The story is not just about Jesus—it is about those who were “chosen” to follow him, real flesh-and-blood people who, for most of us, are stained glass windows or icons rather then normal human beings. “The Chosen” is changing that perception.

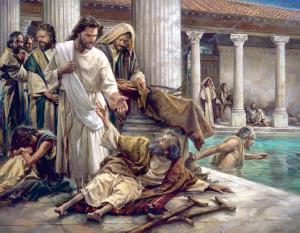

Each episode of “The Chosen” usually focuses on one story from the gospels: a miracle, an important encounter, the call of a new disciple. The most recent episode focuses on the events of John 5, the lame man who has been at the Pool of Bethesda, rumored to have healing powers if one gets into the water when it is intermittently “stirred up.” The guy has been there for thirty-eight years, according to the Gospels. In one way, it’s just one of many miracle stories, but embedded in the narrative is an odd, but profound question that Jesus asks the man at the beginning of their encounter.

Each episode of “The Chosen” usually focuses on one story from the gospels: a miracle, an important encounter, the call of a new disciple. The most recent episode focuses on the events of John 5, the lame man who has been at the Pool of Bethesda, rumored to have healing powers if one gets into the water when it is intermittently “stirred up.” The guy has been there for thirty-eight years, according to the Gospels. In one way, it’s just one of many miracle stories, but embedded in the narrative is an odd, but profound question that Jesus asks the man at the beginning of their encounter.

The story is strange enough that it came up in one of the thirty half-hour oral exams that my teaching colleague and I have conducted over the past week in our “Grace, Truth, and Freedom in the Nazi Era” colloquium. One of the authors we considered during the semester was Simone Weil, who suggests that attentive listening, what she calls “attention,” is the first step to bringing those who are “afflicted,” persons whose identity has been stripped from them either by chance or deliberately by others, back toward healing and a restoration of their humanity. Think of the emaciated, skeletal prisoners of Auschwitz on the day that Allied soldiers liberated the death camp. I’m sure you’ve seen the pictures or film footage. These are people from whom every shred of dignity, identity, and humanity has been stripped. They are the walking dead. And, to use Simone Weil’s word, they are “afflicted.”

The temptation, of course, is to seek to address the most obvious physical needs of such persons—food, clothing, shelter, medical care, and so on. But, Weil suggests, there is something more profound and immediate than physical help that those who are afflicted need. She writes that

Those who are unhappy have no need for anything in this world but people capable of giving them their attention. The capacity to give one’s attention to a sufferer is a very rare and difficult thing; it is almost a miracle; it is a miracle . . . The love of our neighbor in all its fullness simply means being able to say to him: “What are you going through?” It is a recognition that the sufferer exists, not only as a unit in a collection, or a specimen from the social category labeled “unfortunate,” but as a man, exactly like us, who was one day stamped with a special mark by affliction.

How do I begin to restore the humanity and dignity of one from who those things have been violently stripped away? Not by addressing their physical needs as one would solve a mathematical equation, but rather by saying “tell me your story.” In this way, Simone Weil argues, I tell the afflicted person—to use a current popular phrase—“I see you. At the core of this starving, filthy, corpse-like creature in front of me I recognize a fellow human being. What are you going through?” And in that way, through the simple but profound recognition of another’s personhood, the restoration of human dignity begins.

Many of our colloquium students found Weil’s thought challenging, but profound. As my colleague and I conversed with one of our students, the story of the man at the pool of Bethesda occurred to me. After briefly describing the story which, as it turned out, she was familiar with, I said “We know that Jesus is going to heal this guy. But instead of just getting down to business, he firsts asks the strangest question: Do you want to be healed? Why does Jesus ask such a seemingly dumb question?”

At first, the student speculated that perhaps this man made his meagre living begging as a lame man. Jesus is asking him “Are you sure you are prepared for the consequences of no longer being lame?” The man no longer will be able to make money begging if he can walk. But after some further conversation, she suggested instead that perhaps Jesus is exhibiting Simone Weil’s attentiveness. By asking for the man’s consent, Jesus shows that he does not consider the lame man as a problem to be solved or a disease to be cured, but considers him rather as a person, a human being with dignity, whose permission is needed simply because he is a human being equal in dignity to the one who is asking him the question.

In the latest episode of “The Chosen,” the lame man at the pool is named Jesse. Throughout the episode, we are given several insights into Jesse’s history. He fell when climbing a tree as a kid and broke his back. His family raises him with love (his younger brother is Jesus’ new disciple Simon the Zealot), but he ends up years later, embittered and frustrated, at the Pool of Bethesda. Because he has no one to help him, he cannot get himself into the water before it becomes calm again. Picking him out from dozens of people in similar straits, Jesus begins a brief conversation with his remarkable question.

Jesus: I have a question for you.

Jesse: I don’t have many answers.

Jesus: Do you want to be healed?

Jesse: I’m having a really bad day

Jesus: You’ve been having a bad day for a long time.

Jesse: I have no one to help me into the water, and when I get close, the others step down in front of me.

Jesus: Look at me. That’s not what I asked. I’m not asking about who is helping you, who is not helping you, or who is getting in the way. I am asking about you . . . You don’t need this pool. You only need me. So. Do you want to be healed?

Jesse: (nods, with tears)

Jesus: So let’s go. Get up, pick up your mat, and walk.

And he does.

The scene is striking in its simplicity. Jesus asks Jesse the question because he wants Jesse to know that, despite his affliction, his poverty, his bitterness, and his pain, Jesus recognizes in him the beauty and dignity of a human being. And Jesus will not presume to invade Jesse’s world without Jesse’s consent. There is nothing more profound contained in the story of Christianity than that God became human—and that this was not so much a reflection of how far God had to descend, but rather of how infinitely valuable human beings are. As the traditional Hindu greeting “Namaste” says: “That which is holy in me recognizes that which is holy in you.”