I spend a lot of time thinking and writing about God. That’s a strange thing to spend time doing, given that the very existence of God, and God’s nature if God does exist, has been seriously and vigorously debated since someone first looked into the sky and wondered if anything is out there. What sorts of evidence count for or against? Is certainty possible? And if God exists, which God are we talking about? I am a skeptic both by nature and profession, but I also believe that God exists. How does that work?

Is certainty possible? And if God exists, which God are we talking about? I am a skeptic both by nature and profession, but I also believe that God exists. How does that work?

I was recently reminded by the usual random confluence of events of a way proposed close to five hundred years ago to establish belief in God while at the same time doing an end run on all of the questions above.  The proposer was the seventeenth century French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal; the proposition has come to be known as “Pascal’s Wager,” one of the most debated and controversial arguments any philosopher has ever offered. Pascal was a world-class thinker who found himself knocked on his ass one night by what he interpreted as a direct message from the divine. It changed his life, moving him strongly in a religious direction and causing him to put his mathematical theories on the shelf.

The proposer was the seventeenth century French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal; the proposition has come to be known as “Pascal’s Wager,” one of the most debated and controversial arguments any philosopher has ever offered. Pascal was a world-class thinker who found himself knocked on his ass one night by what he interpreted as a direct message from the divine. It changed his life, moving him strongly in a religious direction and causing him to put his mathematical theories on the shelf.

Pascal lived in a time of skepticism; the medieval worldview had crumbled,  the Scientific Revolution was in full swing, and religious wars were being fought all over Europe. Michel de Montaigne, one of the most eloquent and brilliant skeptics who ever lived, was the most widely read author of the time. Pascal had no doubts about God’s existence—his “Night of Fire” had burned away any uncertainty—but he was smart enough to know that not everyone has such experiences. Lacking direct experiential evidence, and knowing that every philosophical, logical argument for the existence of God has been disputed by other philosophers using logical arguments, what would a betting person do?

the Scientific Revolution was in full swing, and religious wars were being fought all over Europe. Michel de Montaigne, one of the most eloquent and brilliant skeptics who ever lived, was the most widely read author of the time. Pascal had no doubts about God’s existence—his “Night of Fire” had burned away any uncertainty—but he was smart enough to know that not everyone has such experiences. Lacking direct experiential evidence, and knowing that every philosophical, logical argument for the existence of God has been disputed by other philosophers using logical arguments, what would a betting person do?

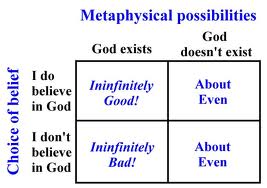

Consider the options, says Pascal. Either you believe that God exists or you don’t, and either God exists or God doesn’t. That means there are four possibilities

1. I believe in God, and God does not exist

2. I do not believe in God, and God does not exist

3. I believe in God, and God exists

4. I do not believe in God, and God exists

Options 1 and 2 are essentially a wash. Believer 1 will probably live her life somewhat differently than Non-believer 2, but at the end of their lives they both are dead. End of story. But if it turns out that God does exist, then everything changes. Believer 3 is set up for an eternity of happiness, while Non-believer 4 is subject to eternal damnation. On the assumption that we cannot know for sure whether God exists but we still have to choose whether to believe or not, it makes betting sense to be a believer than to be a non-believer. As the handy chart below indicates, the believer either lives her life and dies or gets eternal happiness, while the non-believer either lives his life and dies or gets eternal damnation. So be smart and believe. QED.

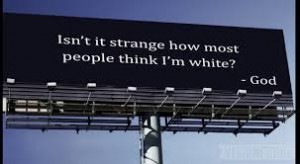

Many silent assumptions are woven into the argument, assumptions that have driven analysis and critique of Pascal’s Wager ever since. For instance, the argument assumes that there is about a 50-50 chance that God exists.  But it could be argued that the preponderance of direct evidence from the world we live in (evil, disease, natural disasters, etc.) counts against God’s existence—the likelihood of God’s nonexistence is far greater than 50 percent. Others have pointed out that the difference between 1 and 2 is not negligible at all. Believer 1 might spend her life denying herself all sorts of experiences and pleasures in the mistaken belief that a nonexistent God doesn’t like such experiences and pleasures, while Non-believer 2 will enjoy such experiences and pleasures to the fullest. And what if God exists but is of an entirely different nature and character than we think? What if the things we believe will please God actually piss God off?

But it could be argued that the preponderance of direct evidence from the world we live in (evil, disease, natural disasters, etc.) counts against God’s existence—the likelihood of God’s nonexistence is far greater than 50 percent. Others have pointed out that the difference between 1 and 2 is not negligible at all. Believer 1 might spend her life denying herself all sorts of experiences and pleasures in the mistaken belief that a nonexistent God doesn’t like such experiences and pleasures, while Non-believer 2 will enjoy such experiences and pleasures to the fullest. And what if God exists but is of an entirely different nature and character than we think? What if the things we believe will please God actually piss God off?

I find such critiques to be compelling and do not find Pascal’s Wager to be an attractive argument at all, but I believe in God’s existence so what do I know? I am far more interested in what Pascal says after the options are laid out to the person who buys the argument but is currently a non-believer. If I don’t believe in God’s existence but am convinced that a smart betting person does believe in God’s existence, how do I make that happen?  How does one manufacture belief in something one does not believe in? Pascal’s advice is revealing.

How does one manufacture belief in something one does not believe in? Pascal’s advice is revealing.

You would like to attain faith and do not know the way; you would like to cure yourself of unbelief and ask the remedy for it. Learn of those who have been bound like you, and who now stake all their possessions. These are people who know the way which you would follow, and who are cured of an ill of which you would be cured. Follow the way by which they began; by acting as if they believed, taking the holy water, having masses said, etc. Even this will naturally make you believe, and deaden your acuteness. What have you to lose?

Pascal is borrowing a technique from Aristotle, who once said that if you want to become courageous, do the things that courageous people do. In this case, do the things believers do and one day you may find you’ve become one.

Pascal came to mind when I read a reader’s comment on my blog entry “The Imposter” a few days ago.

In response to my discussing imposter syndrome and our general human fears about inadequacy and lack of importance, the reader wrote

“Fake it until you make it” is actually almost a principle in Judaism, although not in those words. The medieval work  Sefer Hahinuch, which goes through the 613 commandments of the Torah according to traditional rabbinic calculation, states that a person is affected by his actions. If you do the right thing, little by little it can make you on the inside more like the act you are playing on the outside. Of course you can’t just do it to fool people. You have to intend to fulfill G-d’s will in the world and do things pleasing to Him according to what He has given us to work with. We do our job and keep refining it, and the work, the very inner struggle is pleasing to G-d because we are getting closer, because we are striving to be true to ourselves and Him, even though we know we aren’t there yet and never will be totally. But that is called doing His work.

Sefer Hahinuch, which goes through the 613 commandments of the Torah according to traditional rabbinic calculation, states that a person is affected by his actions. If you do the right thing, little by little it can make you on the inside more like the act you are playing on the outside. Of course you can’t just do it to fool people. You have to intend to fulfill G-d’s will in the world and do things pleasing to Him according to what He has given us to work with. We do our job and keep refining it, and the work, the very inner struggle is pleasing to G-d because we are getting closer, because we are striving to be true to ourselves and Him, even though we know we aren’t there yet and never will be totally. But that is called doing His work.

Although this principle in Judaism reminded me of Pascal’s wager, it is actually very different. The Jewish principle supposes that one accepts that it would be good to live according to the rules and guidelines in the Torah but is not naturally inclined to do so. By putting these rules into action they become my own, all the time believing that becoming a person who does such things habitually is pleasing to God. But whether they are pleasing to God or not, they are arguably making me a better husband, father, son,  neighbor and contributing member of society.

neighbor and contributing member of society.

Pascal’s suggestion is far less demanding, requiring nothing more than going through the motions of certain rituals on a daily or weekly basis. This is not likely to make me a believer or a better person so much as just a person with a very busy Sunday morning every week. In Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the saintly Father Zossima’s advice to an unbeliever who wants to believe is quite different: he recommends the “active and indefatigable love of your neighbor.” Much like the Sefer Hahinuch, Father Zossima provides no shortcuts to belief in God. Rather he recommends the difficult prescription of transforming one’s heart and mind by one’s actions. This doesn’t establish any metaphysical truths, but it does open the door to the good human beings are capable of. Whether God exists or not.