As I begin to prepare for my next book project, a memoir on the teaching and academic life tentatively titled Nice Work if You Can Get It: Lessons and Stories from a LIfe in the Classroom, I’m returning to posts from the recent four years that I was the director of a large program on campus. I learned a lot about myself and others during those years, including some useful quick ways to categorize people that helped me sort out how to work with and lead my 75-80 faculty colleagues who taught in the program I was directing.

I remember one particular conversation with a colleague who insisted that on the particular issue we were discussing, “all or nothing” was the rule—either one took one position or the other, with no room for nuance. All of us have become more and more aware over the past few years that this “all or nothing,” “either/or” attitude is not unusual, no matter the isse at hand. Human beings are hard-wired to categorize things, including each other. This is a survival skill honed over the millennia through the evolutionary process. Faced with an extraordinarily complicated and threatening environment, creatures with the capacity to quickly simplify things by sorting them out into a manageable number of categories have a leg up in terms of survival on creatures who lack this capacity.

But this useful ability that developed in our evolutionary past does not serve us well when applied to many of the complicated and complex matters that contemporary human beings face every day. One of my most important tasks in the classroom is to convince my students that reality is not neatly and cleanly divided up into familiar or comfortable categories. As William James wrote, “In the great boarding-house of nature, the cakes and the butter and the syrup seldom come out so even and leave the plates so clean.” Our current political dysfunction is at least partially due to our insistence on reducing every issue, from abortion to climate change, from immigration to health care, from vaccinations to masks, to sharply opposed and incompatible options. Compromise, which has historically been the lifeblood of social policy and politics, has become a dirty word. All or nothing. This or that. Make a choice.

“In the great boarding-house of nature, the cakes and the butter and the syrup seldom come out so even and leave the plates so clean.” Our current political dysfunction is at least partially due to our insistence on reducing every issue, from abortion to climate change, from immigration to health care, from vaccinations to masks, to sharply opposed and incompatible options. Compromise, which has historically been the lifeblood of social policy and politics, has become a dirty word. All or nothing. This or that. Make a choice.

As important as compromise is, I must admit that quick and rough division into recognizable categories is one of the most useful tools available for trying to understand ourselves and the world around us. I have written about my favorite categories for understanding human nature on occasion in this blog over the past decade—here are a few of them.

Hedgehog/Fox: Archilochus’s observation that “the hedgehog knows one big thing,  but the fox knows many little things” is so indispensable to understanding authors, colleagues, friends and family that I have written about it twice, once in the form of a primer

but the fox knows many little things” is so indispensable to understanding authors, colleagues, friends and family that I have written about it twice, once in the form of a primer

and another time discussing how I use the hedgehog/fox distinction both in teaching and in administration.

How to Herd a Hedgehog (or a Fox)

Another useful way to talk about this difference is to ask whether a person is a “bottom-up” individual (details first, then big picture) or “top-down” (big picture first, applied then to the details).  I am both by nature and philosophical orientation far more fox-like than hedgehoggy, preferring the messiness of details to the pristine purity of the big picture, but I try to remember that none of these distinctions are value-laden. One is not better than the other—they are just very different. Each of us runs into trouble when we assume that our way is not only ours but also is universally best, then act on that assumption.

I am both by nature and philosophical orientation far more fox-like than hedgehoggy, preferring the messiness of details to the pristine purity of the big picture, but I try to remember that none of these distinctions are value-laden. One is not better than the other—they are just very different. Each of us runs into trouble when we assume that our way is not only ours but also is universally best, then act on that assumption.

Cromwell/More: This distinction is about change and certainty—with which are you more comfortable? In my estimation, this is the most useful teaching tool in my arsenal when introducing students to the pantheon of philosophers in the Western tradition for the first time. Two great streams of philosophical thought flow from deciding which is more important to focus on as we try to decipher ourselves and our world. In the certainty camp can be found Protagoras, Plato, Descartes, Hegel, and most of the great metaphysical system builders of the past two millennia and more, while Heraclitus, Aristotle, Locke, Hume and the great empiricists focus their attention on the importance of change. I have named this distinction Cromwell/More because of the following passage from  Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, around which I built a discussion of this distinction a few months ago.

Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, around which I built a discussion of this distinction a few months ago.

He [Cromwell] never sees More . . . without wanting to ask him, what’s wrong with you? Or what’s wrong with me? Why does everything you know, and everything you’ve learned, confirm you in what you believed before? Whereas in my case, what I grew up with, and what I thought I believed, is chipped away a little and a little, a fragment then a piece and then a piece more. With every month that passes, the corners are knocked off the certainties of this world: and the next world too. Show me where it says, in the Bible, “purgatory.” Show me where it says “relics, monks, nuns.” Show me where it says “Pope.”

Although I am thoroughly Cromwellian in all facets of my life, I try to remember—although it is often difficult—that for many people certainty is both a refuge and a requirement (even though I often say that it is vastly overrated).

High maintenance/Low Maintenance: For those blessed with administrative and leadership duties, the most important matter to become clear about as soon as possible is who the high maintenance people are. The low maintenance people are those you will never hear from—they just do their jobs. Toward the end of my time as director of the program I mentioned earlier, I wrote about how this distinction effected my scheduling of classes for the next academic year.

High maintenance/Low Maintenance: For those blessed with administrative and leadership duties, the most important matter to become clear about as soon as possible is who the high maintenance people are. The low maintenance people are those you will never hear from—they just do their jobs. Toward the end of my time as director of the program I mentioned earlier, I wrote about how this distinction effected my scheduling of classes for the next academic year.

In review I realize that I probably was as too critical of high maintenance people in that essay. From the perspective of an administrator, it is difficult not to start resenting the five percent of people you are responsible for who take up ninety percent of your time and are responsible for ninety percent of your headaches. Over time I have frequently been surprised by how often high maintenance people take pride in being high maintenance.  Any time you hear a person say that “the squeaky wheel gets the grease,” that person is almost certainly a high maintenance person giving you a soundbite explaining why they are the way they are. It’s their way of getting things done. If someone doesn’t stir the pot, nothing will happen. And (I can’t believe I’m saying this) thank God for high maintenance people—just as long as they are using their abilities for the good of everyone instead of just themselves. And thank God that a significant minority of people are high maintenance. My prescription for what ails our current dysfunctional Congress and political world at large? Stop electing so many high maintenance people.

Any time you hear a person say that “the squeaky wheel gets the grease,” that person is almost certainly a high maintenance person giving you a soundbite explaining why they are the way they are. It’s their way of getting things done. If someone doesn’t stir the pot, nothing will happen. And (I can’t believe I’m saying this) thank God for high maintenance people—just as long as they are using their abilities for the good of everyone instead of just themselves. And thank God that a significant minority of people are high maintenance. My prescription for what ails our current dysfunctional Congress and political world at large? Stop electing so many high maintenance people.

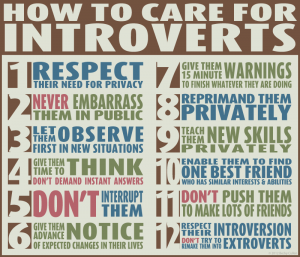

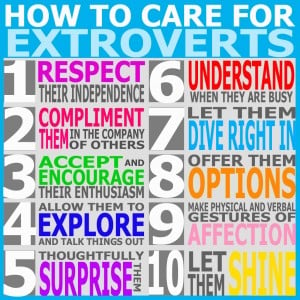

Introvert/Extrovert: You knew this one was coming. I ruminate about the joys of introversion and the frightening aspects of extroverts frequently; today, I’ll simply take note of two very helpful checklists that have been making the rounds on social media and elsewhere for a while now.

As I look these over, I am astounded by how well my extraordinarily extroverted wife abides by the rules of taking care of people like me, particularly because when we first got together she not only didn’t know anything about these rules but didn’t seem to even be aware that introverts exist.  Spending a bit of time with her extended Italian/Irish family will explain why—there are no introverts in sight. I only hope that I am continuing to learn to let her shine and talk things out as well as she has learned to respect my need for privacy and silence as well as my lack of need for dozens of friends. For those strongly on one side of this divide in relationship with someone strongly on the other side, I suggest that you find a couple of things that you both love where you can focus your shared energies. Dogs, Prime video, Netflix, and God do quite well.

Spending a bit of time with her extended Italian/Irish family will explain why—there are no introverts in sight. I only hope that I am continuing to learn to let her shine and talk things out as well as she has learned to respect my need for privacy and silence as well as my lack of need for dozens of friends. For those strongly on one side of this divide in relationship with someone strongly on the other side, I suggest that you find a couple of things that you both love where you can focus your shared energies. Dogs, Prime video, Netflix, and God do quite well.

Everyone uses these quick and effective tools to sort out a complicated world—there’s nothing wrong with that. The trick is not to impose moral values on traits that are, for the most part, hard-wired in each of us as default settings. Vive la difference!