I n the early hours of a Sunday morning not long ago, I read the final pages of Daša Drndić’s Trieste, the most powerful, unrelenting and unforgiving book related to the Holocaust I have ever read. As a reviewer for Amazon wrote, “Trieste is not a book for the faint-hearted, either in style or subject. . . . Enter if you are brave enough, and if you stay the course you will be changed.” No one—those in authority, the church, those who turned their heads, those who simply did whatever they could to stay alive—are spared in this brutally honest and unflinching account of what human beings are capable of.

n the early hours of a Sunday morning not long ago, I read the final pages of Daša Drndić’s Trieste, the most powerful, unrelenting and unforgiving book related to the Holocaust I have ever read. As a reviewer for Amazon wrote, “Trieste is not a book for the faint-hearted, either in style or subject. . . . Enter if you are brave enough, and if you stay the course you will be changed.” No one—those in authority, the church, those who turned their heads, those who simply did whatever they could to stay alive—are spared in this brutally honest and unflinching account of what human beings are capable of.

As I read I was reminded of something a post-Holocaust Jewish theologian wrote: “No statement, theological or otherwise, should be made that would not be credible in the presence of the burning children.”  With regard to those men who were at the same time both murderous killers and yet tender fathers and husbands, Drndić writes that a father is not “a sacrosanct being. . . . There are no sacrosanct beings. Even God is not sacrosanct, perhaps He least of all.” To those who wish to excuse the culpable silence and frequent collaboration of religious institutions, she writes that “this caricatured parade and more than revolting fabrication, this costumed theatre of transparent lies and empty promises should be done away with right now, once and for all.”

With regard to those men who were at the same time both murderous killers and yet tender fathers and husbands, Drndić writes that a father is not “a sacrosanct being. . . . There are no sacrosanct beings. Even God is not sacrosanct, perhaps He least of all.” To those who wish to excuse the culpable silence and frequent collaboration of religious institutions, she writes that “this caricatured parade and more than revolting fabrication, this costumed theatre of transparent lies and empty promises should be done away with right now, once and for all.”

And then Jeanne and I went to church. I was lector, she was chalice bearer—we couldn’t skip, but I was hardly in the mood. I was responsible for the Isaiah reading from the Jewish scriptures, a text I had briefly glanced at during the week, describing it to Jeanne as “kind of weird.” At the lectern, I found myself channeling something unexpectedly disturbing.

Isaiah 58 begins with the prophet mimicking the complaints of the “house of Jacob”: We have been fasting and humbling ourselves, just as you require. Why aren’t you answering our prayers? Why aren’t you taking notice? In response the prophet laughs with the voice of God.  “Look, you serve your own interest on your fast-day, and oppress all your workers. Look, you fast only to quarrel and to fight. Is such the fast that I choose? . . . Is it to bow down the head like a bulrush, and to lie in sackcloth and ashes?” In other words, your “fast-day” is all about you. It’s all about your pitiful and self-centered attempts to twist divine favor in your direction. It’s all about having convinced yourself that skipping a few meals, attending a few extra meetings at your preferred house of worship, that arguing with each other about which forms of ritual are best, are all that it takes to draw God’s favorable attention. “You call this a fast, a day acceptable to the Lord?”

“Look, you serve your own interest on your fast-day, and oppress all your workers. Look, you fast only to quarrel and to fight. Is such the fast that I choose? . . . Is it to bow down the head like a bulrush, and to lie in sackcloth and ashes?” In other words, your “fast-day” is all about you. It’s all about your pitiful and self-centered attempts to twist divine favor in your direction. It’s all about having convinced yourself that skipping a few meals, attending a few extra meetings at your preferred house of worship, that arguing with each other about which forms of ritual are best, are all that it takes to draw God’s favorable attention. “You call this a fast, a day acceptable to the Lord?”

You want to know what a real fast-day would be like? What it would really be like if you humbled yourselves? Here’s a clue:

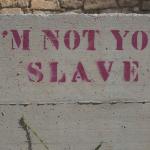

To loose the bonds of injustice

To loose the bonds of injustice

To undo the thongs of the yoke

To let the oppressed go free

To share your bread with the hungry

To bring the homeless and poor into your house

To cover the naked when you see them

Try doing that for a while and see what happens.

As I considered in a post shortly after the November election, Jesus says this sort of thing frequently in the Gospels.

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/freelancechristianity/blessed/

But in Isaiah’s prophetic tones, the call to attend to the hungry, poor, widows and orphans is not a suggestion or an invitation to try out something new, as we might mistakenly read the New Testament texts.  The text from Isaiah is a flat out command. Just f–king do it. And until you do, stop pretending that you are anything other than a self-centered piece of crap. And stop expecting anything other than a perpetuation of the continuing, sad human story of injustice and violence. Period.

The text from Isaiah is a flat out command. Just f–king do it. And until you do, stop pretending that you are anything other than a self-centered piece of crap. And stop expecting anything other than a perpetuation of the continuing, sad human story of injustice and violence. Period.

As I haphazardly told Jeanne about some of the difficult aspects of Trieste on the drive to church, she said “I hope I die before this all happens again. Because it will—eventually no one will remember.” As my teaching colleague and I proceed through the early weeks of our colloquium on the Nazi era with very bright nineteen- and twenty-year-olds, the most frequent sort of question raised is “How could they have done this?” or “How could people have gone along with those who were doing this?” Trieste has convinced me that before proceeding with these students, for whom the Holocaust is history as ancient as Julius Caesar and Pericles, to love, grace, truth and freedom in the midst of horror, perhaps more time should be spent in the horror part. No one in Trieste dropped in from an evil planet other than Earth—each person is a human being with darkness ready to erupt when inattentiveness and self-interest push common human decency into the background.

“How could they have done this?” or “How could people have gone along with those who were doing this?” Trieste has convinced me that before proceeding with these students, for whom the Holocaust is history as ancient as Julius Caesar and Pericles, to love, grace, truth and freedom in the midst of horror, perhaps more time should be spent in the horror part. No one in Trieste dropped in from an evil planet other than Earth—each person is a human being with darkness ready to erupt when inattentiveness and self-interest push common human decency into the background.

When one of the characters in Albert Camus’ The Plague is described as a “saint,” he responds “I have no interest in being a saint. I’m more interested in being a man.” This strikes me as a good place to start. A central problem illuminated by texts such as Isaiah and Trieste is the powerful human tendency to set the moral bar so low that even the most basic moral behavior looks like heroism or sainthood—a standard perhaps to be admired but not one that I hold myself to. We are told in sacred texts over and over again that God demands that we be fundamentally aware of each other. But the belief that basic morality and common decency require a conscious awareness of needs other than our own, particularly those of other human beings, need not be rooted in religious faith or practice. Whatever it takes to convince even a few of us that not only our thriving, but our very existence and survival depends on expanding the membership of our moral community to more than one is worth hanging on to.

When one of the characters in Albert Camus’ The Plague is described as a “saint,” he responds “I have no interest in being a saint. I’m more interested in being a man.” This strikes me as a good place to start. A central problem illuminated by texts such as Isaiah and Trieste is the powerful human tendency to set the moral bar so low that even the most basic moral behavior looks like heroism or sainthood—a standard perhaps to be admired but not one that I hold myself to. We are told in sacred texts over and over again that God demands that we be fundamentally aware of each other. But the belief that basic morality and common decency require a conscious awareness of needs other than our own, particularly those of other human beings, need not be rooted in religious faith or practice. Whatever it takes to convince even a few of us that not only our thriving, but our very existence and survival depends on expanding the membership of our moral community to more than one is worth hanging on to.

On the final page of The Plague, at the end of a harrowing tale of individuals fighting against an out-of-control evil that could not be stopped, the main character Dr. Rieux takes stock of what he has learned now that the plague has left as inexplicably as it came. “He knew that the tale he had to tell could not be one of a final victory. It could be only the record of what had had to be done, and what assuredly would have to be done again in the never ending fight against terror and its relentless onslaughts, despite their personal afflictions, by all who, while unable to be saint but refusing to bow down to pestilences, strive their utmost to be healers.”  This is both a thankless and glorious assignment, one that William James in “The Will to Believe” recommends that we embrace with enthusiasm:

This is both a thankless and glorious assignment, one that William James in “The Will to Believe” recommends that we embrace with enthusiasm:

For my own part, I do not know what the sweat and blood and tragedy of this life mean, if they mean anything short of this. If this life be not a real fight, in which something is eternally gained for the universe by success, it is no better than a game of private theatricals from which one may withdraw at will. But it feels like a real fight,—as if there were something really wild in the universe which we, with all our idealities and faithfulnesses, are needed to redeem; and first of all to redeem our own hearts from atheisms and fears.