The gospel reading for last Sunday was the Beatitudes from Matthew’s gospel. It seems appropriate to return there in the aftermath of Tuesday’s election . . .

It is a scene so familiar in our imaginations that it has become iconic. In films, on television, the subject of countless artistic renditions, we are transported back two thousand years. It is a beautiful, cloudless day.  Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people have gathered in the countryside from miles around; some have walked for hours. On the top of a hill in the middle of the impromptu gathering is the man everybody has been talking about and has gathered to check out. He doesn’t look any different from any number of other guys in the crowd. In spite of the stories that seem to pop up everywhere this guy goes, you would not have been able to pick him out of a crowd. Then he opens his mouth, and the world is forever changed.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people have gathered in the countryside from miles around; some have walked for hours. On the top of a hill in the middle of the impromptu gathering is the man everybody has been talking about and has gathered to check out. He doesn’t look any different from any number of other guys in the crowd. In spite of the stories that seem to pop up everywhere this guy goes, you would not have been able to pick him out of a crowd. Then he opens his mouth, and the world is forever changed.

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account.

Rejoice and be glad, for great is your reward in heaven.

We don’t know the details of the setting, of course—the traditional images are evocations of centuries of imagination. Maybe it was a cloudy and windy day. Maybe these words were spoken inside someone’s home or a synagogue. Maybe they were shared in private only with a few intimate friends and confidants. Maybe the man never spoke these words at all and they are intended as a brief summary, written decades after the fact, of how he lived and called others to live.  But the Beatitudes, the opening lines of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s gospel account, are so beautifully poetic, so rich yet sparse, so gentle yet powerful, so all-encompassing and embracing that over the centuries they have seeped into the Christian ethos as the summary expression, as the “mission statement” if you will, of a religion and all it professes to stand for. In many ways the Beatitudes are as familiar as the Lord’s Prayer and the Twenty-Third Psalm—and this is unfortunate. For the beauty and familiarity of the language can easily disguise what is most remarkable about the Beatitudes—they are a crystal clear call to radically uproot everything we think we know about value, about what is important, about prestige, about power, and even about God.

But the Beatitudes, the opening lines of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s gospel account, are so beautifully poetic, so rich yet sparse, so gentle yet powerful, so all-encompassing and embracing that over the centuries they have seeped into the Christian ethos as the summary expression, as the “mission statement” if you will, of a religion and all it professes to stand for. In many ways the Beatitudes are as familiar as the Lord’s Prayer and the Twenty-Third Psalm—and this is unfortunate. For the beauty and familiarity of the language can easily disguise what is most remarkable about the Beatitudes—they are a crystal clear call to radically uproot everything we think we know about value, about what is important, about prestige, about power, and even about God.  They are a challenge to fundamentally change the world.

They are a challenge to fundamentally change the world.

The Roman-dominated world into which these words came like a lightning-bolt was not that different from our own. One’s status or rank in the social hierarchy depended on power, birth, economic status, education, gender, race—usually some combination of the above. Those who lacked these qualities, whether through their own fault or because of matters entirely outside their control, had little opportunity to rise above their lowly state. And this, it was assumed then as it often is now, is simply the way of the world, the way things work. In a matter of a few brief, poetic lines Jesus turns it all upside down. In God’s economy, none of our assumptions can be relied upon and none of our common sense arrangements work. God’s values are apparently the very opposite of those produced by our natural human wiring.  Throughout the rest of the Sermon on the Mount, and consistently throughout virtually everything we have that is attributed to Jesus in the gospels, the point is driven home. God is most directly found in the poor, the widows, the orphans, those for whom pretensions of being something or having influence are unavailable. The gospels are clear that the one thing guaranteed to make God angry is to ignore such persons. The infrequent times that Jesus talks about hell is always in the context of people who spend their life ignoring the unfortunate. Because in truth we all are impoverished, we all are abandoned, we all are incapable of taking care of ourselves, let alone anyone else. The poor, widows and orphans simply no longer have the luxury of pretending otherwise.

Throughout the rest of the Sermon on the Mount, and consistently throughout virtually everything we have that is attributed to Jesus in the gospels, the point is driven home. God is most directly found in the poor, the widows, the orphans, those for whom pretensions of being something or having influence are unavailable. The gospels are clear that the one thing guaranteed to make God angry is to ignore such persons. The infrequent times that Jesus talks about hell is always in the context of people who spend their life ignoring the unfortunate. Because in truth we all are impoverished, we all are abandoned, we all are incapable of taking care of ourselves, let alone anyone else. The poor, widows and orphans simply no longer have the luxury of pretending otherwise.

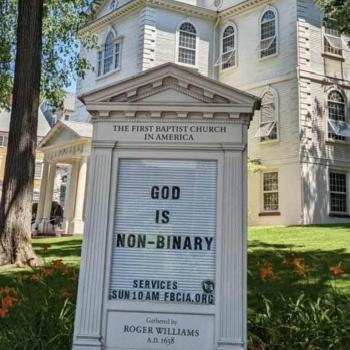

Every once in a while we hear on the news or read online about a community, usually somewhere in the South, in which a debate has arisen over whether it is permissible to put a plaque or a statue containing the  Ten Commandments in a law court, a state house, or a public school. Because of the commitment to separation of church and state established in the United States Constitution, such attempts are invariably rejected as unconstitutional. And this is a good thing—I’m intensely grateful for the sharp separation of church and state. But imagine a community or a society with governing practices and policies infused with the energy, not of the Ten Commandments, but of the Beatitudes. Imagine a legislative body whose guiding north star was the mercy and compassion of the Beatitudes rather than the cold and clinical justice of the Ten Commandments. How would such a community’s or society’s attitudes and policies concerning the poor, the disenfranchised, those who are struggling, those who have fallen through the cracks, change as it learned to see such “unfortunates” not as a problem, but rather as the very face of God?

Ten Commandments in a law court, a state house, or a public school. Because of the commitment to separation of church and state established in the United States Constitution, such attempts are invariably rejected as unconstitutional. And this is a good thing—I’m intensely grateful for the sharp separation of church and state. But imagine a community or a society with governing practices and policies infused with the energy, not of the Ten Commandments, but of the Beatitudes. Imagine a legislative body whose guiding north star was the mercy and compassion of the Beatitudes rather than the cold and clinical justice of the Ten Commandments. How would such a community’s or society’s attitudes and policies concerning the poor, the disenfranchised, those who are struggling, those who have fallen through the cracks, change as it learned to see such “unfortunates” not as a problem, but rather as the very face of God?

An intriguing thought experiment, but ultimately the Beatitudes are not about transformed social institutions. They are about a transformational way of being in the world. The Beatitudes are far more than a beautifully poetic literary statement. They are the road map for how to carry our faith into the real world. The world we live in is no more naturally attuned to the challenge of the Beatitudes than was the world in which they were first spoken.  Individuals infected with the energy of the Beatitudes are those whose responsibility it is to help transform reality. As Joan Chittister writes,

Individuals infected with the energy of the Beatitudes are those whose responsibility it is to help transform reality. As Joan Chittister writes,

Having made the world, having given it everything it needs to continue, having brought it to the point of abundance and possibility and dynamism, God left it for us to finish. God left it to us to be the mercy and the justice,  the charity and the care, the righteousness and the commitment, all that it will take for people to bring the goodness of God to outweigh the rest.

the charity and the care, the righteousness and the commitment, all that it will take for people to bring the goodness of God to outweigh the rest.

Or as Annie Dillard tersely puts it, God’s works are as good as we make them. The Beatitudes are a call to get to work.