Organized religion often is a source of packaged answers and comfortable solutions to important questions about God and ourselves. Oneof today’s lectionary reading options from the Jewish scriptures is one of my favorites.. It suggests that eventually such answers and solutions must be left behind.

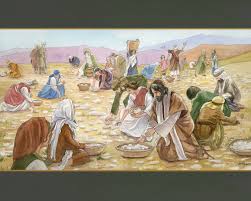

In Exodus, the Israelites (who were miraculously delivered from the pursuing Egyptian armies by the parting of the Red Sea a few chapters earlier), are complaining. And with good reason, because they are hungry in the middle of a desert with no food in sight—and as far as they are concerned, it’s God’s fault. “At least when we were slaves in Israel, we had enough food to eat,” they moan—which may be a case of selective memory.

God’s solution to their predicament is direct and, to me at least, somewhat amusing. “You want food?? I’ll drop so much meat on you in the evening and so much bread in the morning that you won’t be able to figure out what to do with it all!” The white material left on the bushes and ground in the morning after the dew evaporates is confusing to the Israelites—“WTF is this??” they ask. “Man hu” in Hebrew, from which we get the word “manna.”

Manna turns out to be an Israelite culinary staple for the four decades of wandering in the wilderness. Not surprisingly, they get sick of eating the same damn thing for every meal—in Numbers, their dissatisfaction with their diet plays an important role in the development of a new leadership structure for the tribes. We find the liberated Israelites complaining—again. Everyone is pining for the wonderful variety of food they remember eating in Egypt. “We remember the fish we used to eat in Egypt for nothing, the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic; but now our strength is dried up, and there is nothing at all but this manna to look at.”

Of course, they have conveniently forgotten that when they were in Egypt, they were freaking slaves. God is understandably pissed (this is not the first time these complaints have arisen), and Moses is also annoyed. But Moses’ annoyance isn’t just with this rabble of complainers he is in charge of; he’s had it up to here with the Big Guy as well. He’s feeling overworked, overstressed, and unappreciated. After some negotiation with God and some creative input from Moses’ father-in-law Jethro, a new bureaucratic structure of authority is devised and everyone is happy—until the next time.

We discover in the Gospel of John that the Jews of Jesus’ day still took great pride in the fact that God loved their ancestors so much that they were fed for forty years with heavenly miracle food. But, as Jesus tells his Jewish brethren, eating manna apparently wasn’t that special. “Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died.” Manna was a temporary stopgap to address an immediate need, not something to memorialize or interpret as proof that you are special.

If the Jews of Jesus’ day had been more familiar with their own scriptures, they would have known that God is no longer in the manna business. In the book of Joshua we learn that, at least with reference to the children of Israel, God went out of that business as soon as the Israelites crossed the Jordan River. Early in the book, the Israelites cross that river and enter the land that has been promised to them, even though it is already occupied by nomadic tribes and city dwellers who are under the apparently mistaken impression that since they already have been living there for generations, it belongs to them.

After forty years of wandering in the wilderness, a whole generation of Israelites has been born and grown to adulthood who are unfamiliar with the formative traditions underlying their heritage. First, the males of the new generation are all circumcised. After a short recovery period (recently circumcised guys aren’t going to be very good soldiers or anything else), everyone is wondering “What’s next?”

While the Israelites were camped . . . they kept the Passover in the plains of Jericho. On the day after the Passover, on the very day, they ate the produce of the land, unleavened bread and parched grain. The manna ceased on the day they ate the produce of the land, and the Israelites no longer had manna; they ate the crops of the land of Canaan that year.

It is worth noting that on the day after the Israelites celebrated Passover, the very day the manna dried up, “they ate the produce of the land.” In other words, they raided the fields of the people already living in Canaan—the Israelites had just shown up and had no grain-producing fieldsor fruit-producing trees of their own yet. When the divine handouts and support systems dry up, one needs to get creative.

The story of manna is both a coming-of-age story and a cautionary tale about not holding on to the old when the new is right in front of us. It could also be required reading for people who for a time are deservedly dependent on various social support systems and might be tempted to stay on the dole indefinitely. But I am most interested in the story’s spiritual and psychological implications. My Baptist preacher father used to challenge his conservative listeners to “get out of the nursery” and spiritually grow up, noting that a thirty-five-year-old person still in diapers and sucking on a baby bottle would be a rather sad sight.

Yet that’s precisely what traditional religion often does for those it welcomes through its doors. It provides a lifetime of packaged answers and canned responses to important questions about what is greater than us when after a certain time individuals should be struggling with these questions without their hands being perpetually held. I remember being told as a kid in Sunday School that if the Israelites had taken the most natural direct route from Egypt to the Promised Land, it would have taken them no more than a few weeks. Instead it took them forty years, at least partially because they got used to living on divine handouts and the equivalent of nourishing baby food. The spiritual and psychological equivalent of manna is spooned out to the congregation in many churches every Sunday.

What is going to replace the reliable divine infusions that are no longer available? It could be anything, including what might seem to be “out of bounds.” In the following chapters of Joshua, the Israelites engage in their first skirmish among many in the extended occupation-of-Canaan campaign that takes up the rest of the book—they lay siege to the walled city of Jericho. With help from a prostitute (who turns out to be a direct ancestor of Jesus) and by marching around the city until the walls fall down, Jericho is taken. Apparently divine help is still available—it just isn’t going to come in the package that we have become accustomed to.