The first text in the new “Faith and Doubt” colloquium that I am team-teaching this semester was Anne Lamott’s Plan B: Further Thoughts on Faith. Plan B is a sequel to Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith; I remember clearly when, a number of years ago, I picked up Traveling Mercies from a table of new paperbacks in Borders (back when Borders still existed). I’m always drawn to any book outside the Religion, Theology, Spirituality, or New Age section of a bookstore with the F-word in it, so I took a look. It contained many of the things that I love when reading a book from the “Spirituality” section: irreverence, sarcasm, God-obsession, brutal honesty, social activism, a heart of gold . . . what’s not to like?

I’m always drawn to any book outside the Religion, Theology, Spirituality, or New Age section of a bookstore with the F-word in it, so I took a look. It contained many of the things that I love when reading a book from the “Spirituality” section: irreverence, sarcasm, God-obsession, brutal honesty, social activism, a heart of gold . . . what’s not to like?

As I frequently do when I discover an author, I immediately purchased and read everything Lamott had ever published; over the subsequent years I have waited anxiously for her next publication. I can take or leave her fiction, but her non-fiction comes closer to what I’d like to be able to write myself of anything I’ve ever read. In fact, the best compliment I have ever received concerning my writing is when a colleague, as we were having a couple of afternoon libations at a local watering hole, told me that my essays reminded him of Anne Lamott’s work. I picked up the tab.

A while after discovering Anne Lamott, I came across an equally irreverent voice on the spiritual landscape when I read Pastrix, by Nadia Bolz-Weber. Nadia is what Anne Lamott would have been had she become an ordained Lutheran minister and started her own church. Bolz-Weber came to my attention when, as we were our way to the early show at church one Sunday, Jeanne and I caught a few minutes of Krista Tippett’s NPR show “On Being.”

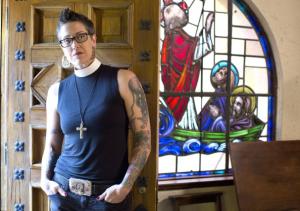

Nadia Bolz-Weber was the guest on this particular Sunday; she’s the tattoo-and-piercings covered, former addict and stand-up comedian Lutheran founder and pastor of the House for All Sinners and Saints (HFASS) church in Denver (a position which she resigned about a year ago in order to pursue new possibilities). She has a sleeve tattoo of the entire liturgical year on her right arm. Things work a bit differently at HFASS, including a blessing of the bicycles liturgy, a chocolate fountain in the baptismal font on Easter, and an occasional event called “Beer and Hymns.” The five or so minutes’ worth of the show we heard on the way to church prompted Jeanne and me to listen to the whole broadcast online once we returned home.

Pastrix is part memoir, part popular theology, and filled with truth that alternates between hilarious, penetratinkristag, and heart-breaking—often on the same page. How can you not love a book by a minister whose first sentence is “‘Shit,’ I thought to myself, ‘I’m going to be late to New Testament class’”? Put that together with an f-bomb or two in each chapter (Nadia’s vocabulary is a bit earthier than Anne Lamott’s, at last in print), and the book is a roller-coaster ride from beginning to end. There are portions that are surprising, jerked me up short, and caused me to think carefully about our natural human self-righteousness and smugness—something that I find myself afflicted by on a regular basis.

Bolz-Weber relates an amusing but telling story about how her open-armed and welcoming attitudes toward all comers to her church was seriously challenged once the word got out that Sunday at the House of All Saints and Sinners was something worth checking out. This church’s raison d’etre is to be a sanctuary and safe haven for persons who have been damaged and rejected by all sorts of churches of every imaginable denomination and description. Outsiders of every stripe—race, sexual orientation, gender, disability, drug addiction, alcoholism, you name it—these are the people who are the founding members of HFASS (as they call it). Creative liturgies and each parishioner having the opportunity to do whatever they feel led to do on a given Sunday (including delivering the sermon) create a dynamic atmosphere of inclusion that cannot help but attract attention. Bolz-Weber has become a rock star and a speaker in great demand (she has also written several more books since Pastrix).

Before long, different sorts of people started showing up for Sunday services—people in suits, soccer moms with well-scrubbed kids in tow, Denver’s equivalent of Wall Street executives—the sorts of folks that one might find in any church on any Sunday morning. And Bolz-Weber was pissed. “I don’t want these people here,” she thought. “My outsider congregation, the people for whom I started this ministry, are going to feel uncomfortable. The newcomers aren’t going to fit in with our free-wheeling, out-of-the-box liturgies.”

As she considered more fully, Nadia realized that she was struggling with a question at least as old as the church itself; as she writes, “Disagreements about ‘inclusion’—about who is in and who is out–began approximately twenty minutes after Christianity started.” Why? Because no matter how open-minded and loving we think we are, no one is comfortable with everyone being included in anything. As Nadia says, “I will always encounter people whom I don’t want in the tent with me.”

Yet we are admonished over and over again in the gospels to pay special attention to the outsider, the disenfranchised, those who fall through the cracks no matter what social or religious scheme is operative. Why? Is the outsider, the person radically different from those in my tent, better than me? With the help of Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, I’m beginning to suspect that something different is going on.

Williams suggests that Jesus’s apparent obsession with the outsider is a reminder of our human limitations and inability to create a world in which everyone is included, despite our best efforts and intentions. These limitations show us where the divine resides.

God appears in and through the fact that our ways of arranging the world always leave someone’s interest, welfare or reality out of account. We cannot organize our world so as to leave everyone a possible place. We are unavoidably bound to exclusion as we try to give form to our social and moral life.

Every time I organize my world in a way that makes sense to me, vast categories of human beings fall by the wayside. If I am willing to include those persons in my world only if they are willing to conform to my agenda for them, I am saying, or implying at least, that my peculiar and particular vision of what is right is the only possible vision. Williams writes that the greater and holier challenge is to forego any presumption that I know what is best and to realize instead that

The outsider’s very presence poses a question that reminds me that my account of things, my way of making the world all right and manageable, is an incomplete enterprise that is keeping out God because it lets in the subtle temptation to treat my perspective as if it were God’s.

Strangely enough, the best intended efforts to institutionalize or organize God’s will on earth are always doomed to failure precisely because the divine cannot be institutionalized. Our efforts to bring the gospel into the world must begin with recognizing our own human limitations. Rowan Williams once again:

God is in the connections we cannot make . . . The person who is ‘left over’ . . . reminds me of my own limits; and as I acknowledge the incomplete character of my world of reference and my understanding, I may at least see the seriousness of the question about the fate of those not catered for.