As I work through my book under contract getting it into shape for the editor and publisher by August 15, I am writing new material in addition to editing. Here is the section from the Holy Week chapter called “Monday of Holy Week: You always have the poor.” As an aside (spoiler alert!), the dinner at Lazarus’ house that is the focus of this section gets powerful and dramatic treatment in Season 4 of “The Chosen.” Enjoy!

The gospel readings for the weekdays in Holy Week are from the account in John’s gospel. John does not include a number of familiar stories from Holy Week in the other three gospels (Jesus driving the money changers from the temple and Jesus killing the fig tree, for instance); as with the birth of Jesus narratives, one needs to pay attention to all four gospels to get the full story.

For those who claim to be guided by Christian principles, the Gospel message is clear. In his reported teachings, Jesus never wavers from the message that in the divine economy and social structure, the poor, the widows, and the orphans—the disenfranchised and those who continually fall through the cracks, in other words—are to be considered first. If there is one thing that guarantees divine judgment, it is the failure to show paramount concern for “the least of these.” The poorest deserve the best.

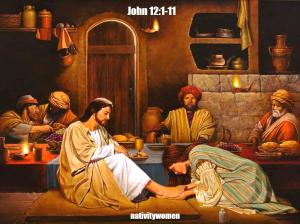

All of which makes the gospel reading for Monday of Holy Week challenging. Jesus is in Bethany at the house of Mary, Martha, and the newly raised Lazarus having dinner. The accounts in Matthew’s and Mark’s gospels say that this dinner was at the house of Simon the Leper and do not name the woman who anoints Jesus, but we can leave that for New Testament scholars to sort out. During the dinner Mary brings an alabaster jar containing spikenard, a rare and expensive ointment, to Jesus, breaks the jar, and anoints Jesus’s feet with the ointment (Matthew and Mark says Jesus’ head is anointed).

All of which makes the gospel reading for Monday of Holy Week challenging. Jesus is in Bethany at the house of Mary, Martha, and the newly raised Lazarus having dinner. The accounts in Matthew’s and Mark’s gospels say that this dinner was at the house of Simon the Leper and do not name the woman who anoints Jesus, but we can leave that for New Testament scholars to sort out. During the dinner Mary brings an alabaster jar containing spikenard, a rare and expensive ointment, to Jesus, breaks the jar, and anoints Jesus’s feet with the ointment (Matthew and Mark says Jesus’ head is anointed).

Mary’s actions earn well-aimed criticism from the disciples and others present. “Why this waste of perfume? It could have been sold for more than a year’s wages and the money given to the poor.” And these critics were absolutely right. The worth of the ointment was about a year’s wages. Spikenard is made from a plant that grows in the Himalayas of northern India and is used as ointment or perfume; according to the text, the worth of the ointment was about 300 denarii, about $54,509 in U.S. dollars. As those present understood Jesus’ teaching, what Mary did was a violation of what has come be known as the “preferential option for the poor.”

Which makes Jesus’s response all the more shocking and confusing.

Leave her alone. She bought it so that she might keep it for the day of my burial. You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me.

Not exactly what the group at dinner expected, I imagine. How to explain this apparent moment of self-centeredness? I have heard many theological explanations for Jesus’s dismissive comment about the poor; I have even heard this very scene twisted into a justification for not funding social programs intended to help those in need.

Why do “the poorest deserve the best”? Not because they are in some strange way better than those who are not poor. The poorest deserve the best because, bottom line, all of us are incurably impoverished. Humanity itself suffers from poverty, the moral and imaginative poverty that time and again reproduces the same patterns of fear and violence. Despite our delusions of independence and self-made success, not one of us, not even the most financially secure and successful or confident law abiding and godly person, can in truth look after ourselves.

The genius of the Christian narrative is that this is not only okay, but it actually is the reason that God became human. In the Jewish scriptures, God frequently tells the children of Israel that they have been chosen precisely because they are slaves and exiles, the most helpless community on the face of the earth. And this is why the poor are to be preferred—they are a constant reminder of the basic condition we all share.

This is also why we will always have the poor with us, why they will always stubbornly resist our best efforts to solve their problems. The poor will always be with us because we cannot escape our collective human impoverishment with exclusively human tools and strategies. Our giant goes with us wherever we go. The divine response? God does not let us have what is left over from the grace given to holy and honorable people. God doesn’t look around for some small bonus that might come from the end-of-year surplus in the budget. God instead becomes one of us, an energizing force for change and reform that we cannot even imagine.

For reflection: We often think of “poverty” in exclusively financial terms, but consider the ways in which each person, even the most financially secure, is impoverished in ways that cannot simply be “fixed.” Compare this to the first of the Beatitudes: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”