This is the first installment of a series of posts by Dr. Yong on the theme of the “Holy Spirit and Mission in Canonical Perspective.”

Gen. 1:3 & 6:3 – Creation and Fall: The Life-Giving Spirit

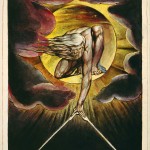

The scriptural canon of course begins with these well-known words: “In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light” (Gen. 1:1-3). Although the Christian New Testament clearly stipulates that all things were created through the Son, the word or Logos of God (John 1:3; Heb. 1:2), these opening words of the Bible indicate that the creative word of God was carried and even spoken through the divine wind or breath (ruah Elohim). If the wind or breath of God is understood also as the spirit of God, then in this ancient words, we have a trinitarian image of the primordial creation: that God fashioned the world through his word and spirit. Even if things are not so simple if we wanted to avoid imposing later understandings on this passage and desired to hear it as its original audience would have heard it, such conclusions are appropriate certainly from a canonical point of view long before we adopt any later historical vantage point.

What is intimated is that we are invited from such a stance to consider the rest of the biblical drama, the entirety of creation’s fortunes, as it were, from such a spirit-oriented or pneumatological perspective. The presence of the divine breath or spirit in effect is what kick-starts the cosmos. Certainly, the movement of God’s spirit initiates the formation of creation that fills in or overcomes the void, and that carries the divine light that counters or disperses the darkness of the deep. In this sense, then, the creative work of God over six days can also be understood pneumatologically, as precipitated by the divine spirit’s sweeping over the primeval waters. By extension, it is the spirit’s elemental stirrings that induces the world’s coming into being and subsequent history, and this also invites us to consider not only the divine creation but also the divine sustenance of the world in pneumatological terms.

But this narrative also announces, even if less explicitly, that the divine spirit’s mission is not only creative but also redemptive. In fact, one might understand divine creation to be redemptive in its opposing the formlessness of the void and in resisting the darkness of the deep. We cannot here resolve the recurrent questions of whether this text teaches an unprecedented creation out of nothing or a creation out of chaos (the “formless void”), but it is clear that the spirit’s creative work is what transforms the chaos into cosmos. From this viewpoint, the formless void symbolizes and calls attention to the chaos that perennially threatens the creation. In the face of this persistent menace, the opening lines of Genesis already announces the sweeping, hovering, and saving work of the divine spirit.

Yet the hazard of this cosmic chaos should never be minimized. The initial lines of Genesis do open up to a creation story that tells of a flourishing world God repeatedly sees as good. Yet hardly has God or his creatures had the opportunity to rest on the seventh day when the creation is plunged back into chaotic disorder with the disobedience of the prehistoric couple, the primal murder, and the banishment of humanity not only from the idyllic garden but also from the company of God. Human beings defiled by sin will have to constantly strive amidst a chaotically cursed environment (Gen. 3:17b, 4:11) and do so as fugitives and wanderers (Gen. 4:15) seeking the divine rest and shalom.

The next time the divine spirit appears is when Yahweh says, “My spirit [ruah] shall not abide in mortals for ever, for they are flesh; their days shall be one hundred and twenty years” (Gen. 6:3). This is a difficult passage for many reasons, not the least of which is that we know little about the “sons of God” and the “Nephilim” referred to in the verses before and following, and therefore do not understand what it means that the latter were said to be “heroes that were of old, warriors of renown” (Gen. 6:4). It would seem as if the Nephilim found a way to survive the Noahic flood since they are found in Canaan later on during the time of Moses and Caleb (Num. 13:33), although the biblical traditions are silent about if and how this might be the case.

Although any attempts to adjudicate these otherwise remarkable allusions will take us too far afield, the pneumatological connections are particularly noteworthy. If in the first few verses of this book the divine wind constrains, if not combats, the watery chaos, here the divine breath is expected to depart from, even disengage with, human mortals. This is surely Yahweh’s counter-threat, imminently carried out, in response to the “wickedness of humankind [that] was great in the earth” (Gen. 6:5). So whereas the creatures of the world are given life through the divine breath (Gen. 1:30, 2:7), the evil and iniquity of humanity now leads the creator to cease animating their flesh, thus effectively ensuring their demise (through the flood). Although there may be some justification for understanding the reference to one hundred and twenty years as denoting the divinely sanctioned upper limits for human life, there are arguably better reasons for thinking it specifies “the period of grace during which the judgment of God upon that generation would be postponed,” until the 600th year of Noah, as it were (see Gen. 7:6).

Noteworthy, though, is that these opening chapters of the biblical canon associate the presence and activity of the divine breath with creation and life on the one hand, and the absence and departure of the same with judgment and death on the other hand. Such connections thus situate the biblical drama of creation, fall, and redemption within an overarching pneumatological framework. Similarly, the mission of God in creation and redemption can be understood also as the mission of the Spirit, even as the twists and turns of human history and the eschaton also now resound with, against, and according to the comings and goings of the wind of God.

Amos Yong came to Fuller Seminary in July 2014 from Regent University School of Divinity, where he taught for nine years, serving most recently as J. Rodman Williams Professor of Theology and dean. Prior to that he was on the faculty at Bethel University in St. Paul, Bethany College of the Assemblies of God, and served as a pastor and worked in Social and Health Services in Vancouver, Washington. Yong’s scholarship has been foundational in Pentecostal theology, interacting with both traditional theological traditions and contemporary contextual theologies—dealing with such themes as the theologies of Christian-Buddhist dialogue, of disability, of hospitality, and of the mission of God. He has authored or edited over 30 volumes.