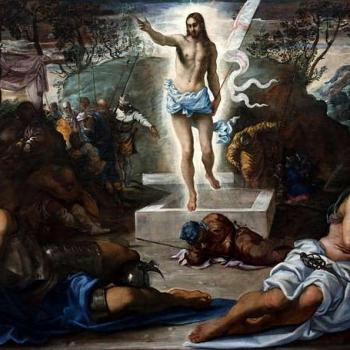

The house lights fade to black. The room falls still as an actor steps from the wings and speaks the simple words that set a plot in motion: “O for a Muse of fire.” “Yes, I have tricks in my pocket, I have things up my sleeve.” “This play is called ‘Our Town.'” Suddenly the outside world vanishes and you’re swept into a parallel universe of excitement and adventure, poetry and magic, fear and hope.

That’s what it feels like to go to the theater and see a great play. But when did you last do so? A week ago? A year? Or do you now prefer to stay home and watch cable television or use Netflix NFLX +0.49% to stream a movie?

If so, you’re one of the reasons why live theater is in trouble.

Take a look at the National Endowment for the Arts’ latest Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, the most statistically reliable study of its kind. Not only did “non-musical play attendance” drop to 8.3% from 12.3% of U.S. adults between 2002 and 2012, but attendance at musicals also fell, to 15.2% from 17.1%, the first time the latter figure has declined since 1985. That’s really bad news. Musical comedy has always been live theater’s bread and butter, the ever-popular fare that never fails to fill the seats. If fewer people want to see “Fiddler on the Roof” or “The Lion King,” then the pillars that hold up American theater are crumbling.

A big part of the problem for New Yorkers is the horrifically high price of tickets to Broadway shows. But 63% of all Broadway tickets are bought by spendthrift tourists. Fortunately, off-Broadway and regional-theater seats don’t cost nearly so much. I just saw a play in Boston, the Huntington Theatre Company’s superb revival of A.R. Gurney’s “The Cocktail Hour,” for which tickets ranged from $25 to $95. (By contrast, the top ticket price for Broadway’s “The Book of Mormon” is a whopping $299.) And the vast majority of professional stage productions, both in New York and in the rest of America, are presented by not-for-profit theaters like the Huntington. These companies, of which there are about 1,800, mounted 14,600 shows in the 2010-11 season, as opposed to 118 commercial productions on Broadway and elsewhere. Yet they, too, view the NEA’s bad-news numbers with alarm, as they readily acknowledge. Even at the top-tier resident regional companies, subscription income, still considered the most reliable yardstick of a resident company’s economic health, is much weaker: Adjusting for inflation, it’s plummeted 13.7% since 2008.

What’s gone wrong with theater? It isn’t a matter of quality control. I’ve been reviewing performances from coast to coast since 2004, and I continue to be impressed by what I see. Instead, what I’m hearing from regional artistic directors is that they’re being slammed by the on-demand mentality.

[Keep reading. . . ]

So do you go to plays anymore, whether professional productions or your local community theater? Just when your child is in a school play?

What’s missing in watching a film by ourselves on Netflix at home, versus going to a theater and watching it with others?

How do you account for our desire to just stay home instead of going out on the town?