Bach wrote liturgical music and choir cantatas built around hymns and Biblical texts. But he also wrote “secular” music and purely instrumental compositions. Some critics try to play those off against each other, to the point of maintaining that Bach was only “free” when he worked without the constraints of religion. But serious scholarship shows that, for Bach, both his church music and his secular music were expressions of his Christian faith and specifically Lutheran theology (which sacralizes the “secular” with the doctrine of vocation).

How, though, can a Christian artist express the faith by means of form alone? That is, for Bach, by means of instrumental music. He would certainly have accepted the principle that faith comes by hearing of the Word, which means that language is necessary for proclaiming the Gospel. And yet, he did things with musical form that also, less directly, carried a Christian meaning.

Michael Marissen, the author of Bach & God, takes up this topic in the New York Times, no less, showing how this plays out in The Brandenburg Concertos. (The link takes you to a performance of them all on YouTube. Many who have said that they don’t like classical music change their tune, so to speak, when they hear these delightful, energetic, and stimulating works.)

I appreciate how our technology allows snippets of the music to be embedded in a work of musical criticism, so that the author can illustrate his observations with the actual music. There are lots more such snippets in the original article, which I encourage you to read. I’ll include a couple, with hopes that they carry over here.

From Michael Marissen, There’s More Religion Than You Think in Bach’s ‘Brandenburgs’, The New York Times:

. . .Each of the six “Brandenburgs” delves into issues of hierarchy and order. The Sixth is musically and socially the most unconventional of the set. Two violas, with cello, are pitted against two viols, with violone.

At the time, violas were customarily low-rent, undemanding orchestral instruments, while viols were high-end, virtuoso solo instruments. Bach reversed these roles, such that the violas perform virtuosic solo lines while the viols amble along in repeated eighth notes. Pursuing these two radical instrumental treatments within the same work was unprecedented (and wouldn’t be imitated)

It’s an excellent musical illustration of the time-honored theme of the “world upside down.” Visual examples include mice chasing cats; servants riding on horseback while noblemen have to go behind on foot; and peasants serving communion in the cathedral while priests sweep the adjacent streets.

These kinds of inversions play a significant part in Christian scripture, which frequently proclaims that with God the first shall be last while the last shall be first; the lowly shall be exalted while the exalted shall be brought low.

The function of the world upside down imagery in Bach’s Lutheranism, as in scripture, was not to foment earthly upheaval, but to inspire heavenly comfort: The hierarchies of this sinful world are a necessary injustice for the sake of order, but, in light of the equality that awaits the blessed in paradise, they are ephemeral.

A marvelous example of inverted imagery in Bach’s church cantatas is the fourth movement of “Whoever lets only the dear God rule” (BWV 93), where a soprano-alto duet gives voice to a hymn text by means of instrument-like countermelodies, while the violins and viola nonverbally intone the actual hymn tune. Voices and instruments, upside down.

All three movements of the Fourth “Brandenburg” feature a solo violin part that is continually overshadowed by a duo of lowly recorders. Today’s listeners revel in the violin’s isolated flurry of activity about three minutes into the first movement:

The audiences at Leopold’s palace, however, would have heard this as an egregious breach of musical and social decorum. The violin’s rowdy flare-up occurs not within an episodic solo section, as it ought properly to have done, but interloping into the start of the group refrain, an elegant French court dance led by the pair of recorders.

A parallel example of a soloist’s hollow virtuosity fluttering atop an elegant dance-like group refrain is the alto aria from Bach’s church cantata “Whoever may love me will keep my word” (BWV 74). Here the violin’s jangling figurations serve to bolster the text’s notion that Jesus’s blood renders the enraged rattling of hell’s chains as comically useless.

[Keep reading. . .]

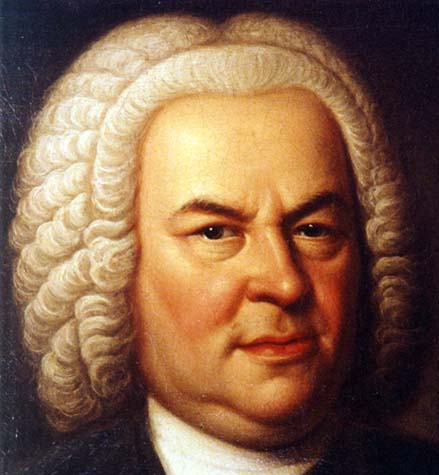

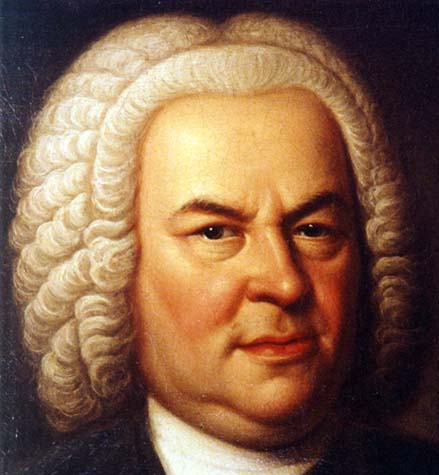

Illustration: detail from Bach portrait by Elias Gottlob Haussmann (1748) [Public domain] via Wikimedia