Can Christians build a perfect society on earth? If not, does that mean that we do nothing to battle the evils in society and improve the world around us? Shouldn’t we at least try? How about in our personal lives? We must strive to obey God, yet our sinful nature often spoils our best efforts. How can we function in this fallen world without succumbing to its pressures, rejecting our this-worldly responsibilities, or repudiating God’s creation?

From Marc LiVecche, Tending the Garden of the Real:

. . . .In the opening chapters of Book 19 [of The City of God], Augustine presents an overview of the Roman scholar Marcus Varro’s 288 theories of the good life. He then rejects all of them as inadequate. Peter Brown, the great Augustine biographer, called this moment “the end of classical thought.” Augustine, contrary to much of the received wisdom of Greco-Roman philosophy that had come before him, is rejecting the idea that the political community can serve as the location in which human beings can be perfected in virtue. Augustine, scholar Gilbert Meilaender suggests, is thereby draining the notion of a “high moral purpose from our understanding of politics.” No political community, Meilaender continues, “can satisfy the restless heart that Augustine evokes in his Confessions.” The political community, for Augustine, is not—it cannot be—ultimate. It cannot, pace Maximus, be redemptive.

If the classical age was ending in Augustine’s desacralizing of the political realm, it might be that the age of Christian realism was just beginning to take root. A stream of political theology that strives to avoid both idealistic sentimentality as well as cynicism, Christian realism brings values to bear on national interests and personal and communal duties to act responsibly and prudentially in pursuit of justice, order and peace in the world. As such, Christian realism is grounded in some basic Augustinian assumptions.

One of these is Augustine’s assertion that political communities are always caught between two “cities.” The first is the city of God, in which peace truly reigns. The second, the city of man, is that rather more quotidian realm in which men are themselves dominated by the lust to dominate others. These cities map rather well on the divided nature of individual human beings. Within every heart vie competing loves. On the one side is caritas—charity—an orientation toward the love of God that manifests in other-centered acts of self-donation. On the other is cupiditas—cupidity—a disordered orientation toward self-love that manifests in self-centered acts of other-donation.

Because of these competing loves, no political realm will ever fully furnish the conditions necessary for peace characterized by justice and order—basic human goods without which no other human good, such as health or life, can long endure. This side of the end of history, any earthly peace we might fashion is going to be unjust, to some degree or another.

That said, Augustine—and the Christian realist—knows that there is much that political communities can do. They can do no harm, they can help where they are able and they can put limits on the human predilection for dominating the helpless. This is not nothing. Maximus was partly right; Rome, probably better than any alternative then on the market, could approximate a kind of peace which, however lacking in perfect justice, was a far sight better than anarchy. Still, the Christian realist—following Christ and not Hobbes—knows that sometimes order and security are not enough, and that a sovereign’s right to rule hinges significantly on their responsibility for the common good.

For all these reasons, Christians retain strong, though limited, respect for secular authority, gratitude for the goods governing powers provide and appreciation for the morally complex dimensions of responsible statecraft. Every Sunday in America, churches across the land pray for the president, the leaders of the nation and those in positions of authority. Importantly, however, for many Christians, such support is not necessarily enough. A primary preoccupation of the Christian realist is figuring out the full extent of Christian responsibility in light of the conditions of the world and the important role of our governing authorities. How Christian realism answers that question helps distance it from other Christian traditions or points of view.

[Keep reading. . . .]

Now Augustine’s Two Cities are not exactly the same as Luther’s Two Kingdoms. Augustine’s model is dualistic, with the “two loves” each city is built upon–love of God vs. love of self–being opposed to each other. For Luther, the two kingdoms are united, despite all of their differences, by their common King. Thus, Augustine’s model manifested itself, in part, in monasticism, with the benefit of withdrawing from the City of Man to devote oneself completely to the love of God. Luther, though, puts a stronger positive value on the “secular” realm and on “earthly” vocations. These are ordained by God by virtue of His creation, and He continually works through them as He providentially governs and cares for His creation.

I would say, though, that Augustine is naming something real that Christians must struggle with, both in their spiritual lives and in their earthly vocations: the conflict between self-love and the love of God. This manifests itself in vocation in the conflict between love of self and love of neighbor. It is resolved in the daily self-sacrifices for our neighbor that our multiple vocations require as we bear the Cross in our callings and serve as “little Christs” to each other. But here too we must practice “Christian realism” as we run into our limits, even as we do our best, trusting the outcomes to God.

How would you apply the principles of Christian realism to issues that we are facing today?

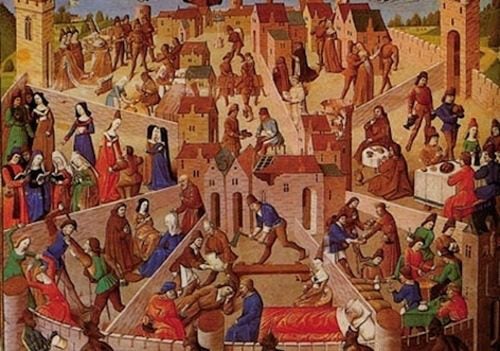

Illustration, The Virtues and Sins, by Raoul de Presles (h.1316-1382) [Public Domain]