Socialism seems to have come into vogue in the United States, at least among young people and our cultural elite. But Matthew Continetti says that America has “antibodies against socialism”–namely, our Constitution and our culture–that always keep socialist movements from getting any traction.

He shows that the polls showing a new openness to socialism are very misleading. For one thing, few of the respondents even know what socialism is. And the same polls show that some of these same fans of socialism still put most of their trust in free market economics.

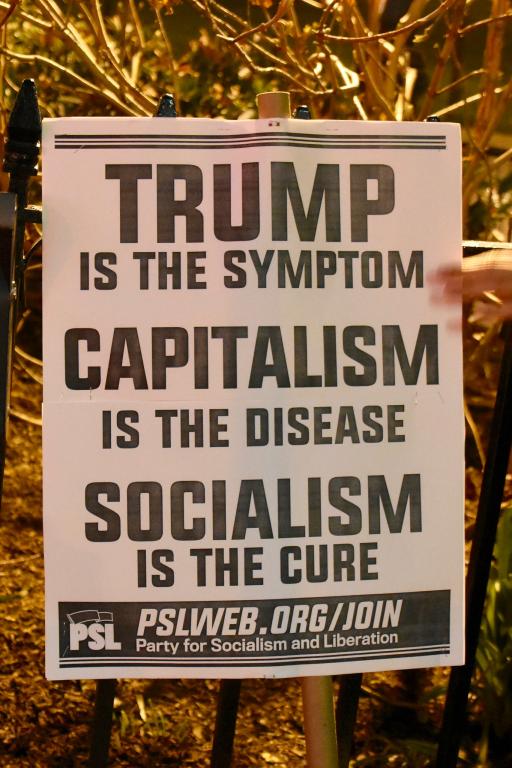

But what I found most interesting in Continetti’s article is his quotation of actual socialists on why the United States is so resistant to their cause. After all, America’s industrial economy would seem to be the most favorable to their ideological analysis. And yet, the workers stubbornly refuse to think they are oppressed and the class struggle never takes off. In fact, America’s working class tends to be among its most conservative demographic. The Teamster’s Union was part of Nixon’s Silent Majority; blue collar workers are Donald Trump’s base. How can that be?

Well, this is evidence that socialist ideology, with its class reductionism, is wrong. But socialist theorists wrestling with the American conundrum do bring out important facets of American society.

Read the whole article, but here are some samples. From Matthew Continetti, America’s Best Defense Against Socialism:

In 1906 the German sociologist Werner Sombart devoted a monograph to answering the question, Why Is There No Socialism in the United States? Sombart noted the comparatively high and rising standard of living of American workers. “On the reefs of roast beef and apple pie,” he said, “socialistic Utopias of every sort are sent to their doom.”. . .

As Max Beer, an Australian socialist of the early twentieth century, wrote,

Even when the time is ripe for a Socialist movement, it can only produce one when the working people form a certain cultural unity, that is, when they have a common language, a common history, a common mode of life. This is the case in Europe, but not in the United States. Its factories, mines, farms, and the organizations based on them are composite bodies, containing the most heterogeneous elements, and lacking stability and the sentiment of solidarity.

When it comes to preventing socialism, diversity really is our strength. . .

The success of identity politics and “woke capitalism” underscores the difficulty of making the sort of class-based appeals Sanders learned at meetings of the Young People’s Socialist League. Americans put their familial, racial, ethnic, and religious attachments ahead of membership in an income or occupational group. Besides, some 70 percent of America considers itself middle class.

One of the reasons the socialist and socialist-curious candidates in the Democratic primary have been arguing against the Electoral College and for expanding the Supreme Court is they understand the challenge the Constitution poses to their dreams. The type of centralization and bureaucratic administration socialism requires is incompatible with a system of federalism, checks and balances, and enumerated powers. Fortunately, structural change is extremely difficult in our vast and squabbling country. It was meant to be. . . .

The good news is America contains antibodies against socialism. As Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Marks wrote in 2000, “Features of the United States that Tocqueville, and many others since, have focused on include its relatively high levels of social egalitarianism, economic productivity, and social mobility (particularly into elite strata), alongside the strength of religion, the weakness of the central state, the earlier timing of electoral democracy, ethnic and racial diversity, and the absence of feudal remnants, especially fixed social classes.”

I would add a few observations: Not only is it a puzzle, from the perspective of a socialist worldview, why American workers have such an antipathy for socialism, the converse is also a problem for economic determinists: how is it that American socialism today is largely a bourgeois phenomenon, an ideology held mainly by the affluent?

In Marxist terms, the American proletariat–whose income and productivity has allowed them to become property owners–is now indistinguishable from the bourgeoisie. That is, American workers have largely entered the American middle class. Not that economic problems and poverty don’t exist in the U.S., but the main issue is unemployment, not economic exploitation of the employed.

Furthermore, the goal of socialism–the collective ownership of the means of production–has largely been realized. Not in state ownership but in the stock market. The nation’s big corporations are now owned not just by the top-hatted capitalist robber barons of socialist mythology but also by pension funds, Individual Retirement Accounts, mutual funds, and similar collective investments that are held not only by “the rich” but also by American white-collar and blue-collar workers.

Photo by Alec Perkins via Flickr, Creative Commons License