Americans are extremely polarized politically. But this is not just a matter of ideology. In fact, most Americans of both parties are flexible when it comes to ideology, holding positions that are pretty centrist and agreeing with each other more than either side would like to admit. Nevertheless, advocates of both parties fear each other, even hate each other. Both sides do little with reasoning or evidence; rather, they try to raise the passions of voters. Ours is now a politics of feelings.

So says Jonathan Rauch in his article in National Affairs entitled Rethinking Polarization. Rauch is a scholar at the liberal think tank the Brookings Institution, and although he uses the Donald Trump phenomenon as his main example, he admits that what he describes had its origins before Trump and occurs on both sides.

Today, as others too have noticed, we do not so much vote for a candidate, as vote against a candidate. Many Trump voters had qualms about his candidacy, but voted for him because they just could not stand Hillary Clinton. Today many people will vote for the Democratic candidate, whoever it is, because they just cannot stand Donald Trump. This is called “negative partisanship,” and it is characterizing not just the national election but state and local elections as well.

Rauch discusses this trend and relates it to another one that scholars have been noticing: “affective polarization.” That is, we are divided by our feelings. Both sides are angry at the other side and their politicians stoke up that anger. Rauch cites research that shows that both sides fear each other. Liberals are afraid of Trump supporters. Leftists say that they do not “feel safe” when conservatives are around, which becomes the excuse to exclude them on college campuses. Conservatives fear that electing a leftist will lead to the end of our liberties, or even the demise of our nation.

Rauch comments, “Increasingly, partisan disagreement is rooted not in policy differences but in a sense of threat — a sense gleefully amplified by demagogues. If the other side wins, our own side’s lifestyles, our values, our very ability to exist will hang by a thread.” He cites the “Flight 93” defense of Trump, the notion that Americans need to rise up in an extraordinary way to save our country, just as the passengers on that doomed 9/11 flight rose up to fight the terrorists. But surely the “sense of threat” has become a staple of Democratic rhetoric: Republicans are accused of waging a “war against women.” A Republican victory will mean “Blacks will go back into slavery.” Evangelicals are plotting to replace American democracy with a theocracy that will be just like it is in Handmaid’s Tale.

Notice too the decline of rational deliberation and debate. “Presenting people with facts that challenge an identity- or group-defining opinion does not work; instead of changing their minds, they will often reject the facts and double down on their false beliefs.” In today’s controversies, both sides are using the same accusation of “fake news.”

Actual ideology–that is, beliefs and policy proposals–hardly matters. Most Americans are in broad agreement. Despite liberals’ accusations, most conservatives are fine with civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights. They even share in beliefs usually associated with liberals, such as being suspicious of big corporations and advocating protectionist economic policies. Liberal Americans also tend to share in beliefs associated with conservatives, such as libertarianism and suspicion of the government.

Rauch also notes the phenomenon of ideological “flipping,” as partisans change their long-held beliefs so as to support their “brand.” He notes how Republican conservatives are tossing aside their own ideology–which traditionally has advocated free trade, balanced budgets, entitlement reform, activist foreign policy, and traditional morality–in their zeal to support Donald Trump, who cuts against the grain of all of these conservative principles. I would add that we see the same thing with Democrats, who used to be the main opponents of illegal immigration, were often pro-life, and opposed same-sex marriage.

From the Greek historians through the authors of the Federalist Papers, thoughtful analysts warned against what could happen to democracy when the people’s “passions” are unleashed. One symptom is the rise of the demagogue, the would-be ruler who stirs up the people’s fears and emotions–often by scapegoating an outside group–as a way of seizing power. Rauch, predictably, cites Trump as exploiting people’s fears of Islamic terrorists and illegal immigrants. But, as George Will, who discusses Rauch’s article from a relatively conservative point of view, points out, it also applies to the other side:

Consider Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s grotesque — and classically demagogic — ascription of blame to unpopular others for everyone else’s personal complaints — which she says government can remedy: “You’ve got things that are broken in your life? I’ll tell you exactly why. It’s because giant corporations, billionaires have seized our government.”

All demagogues begin by rejecting Samuel Johnson’s wisdom: “How small, of all that human hearts endure, that part which laws or kings can cause or cure.” Warren is a millimeter away from Trump’s “I alone can fix it,” where the antecedent of the pronoun “it” is: everything.

Rauch says that these shifts in our politics points to a reversion to a different form of government entirely, a form that the vast majority of humanity has followed throughout the history of the human race: Tribalism. This, he says, is the natural form of government, the kind that is hard-wired into the human brain:

Humans are designed to be tribal. We are wired to organize ourselves socially into in-groups (our own group) and out-groups (others’ groups), and to organize ourselves cognitively so that our reasoning processes and even our sensory perceptions support in-group solidarity.

This often means fighting other tribes, not because of ideological differences, but because of revenge codes, territorial disputes, or ancient rivalries. At issue, fundamentally, is tribal belonging and the need to protect each other and assert one’s tribal identity.

Advanced societies, particularly liberal democracies, have found ways to bind tribes together into nations. But we have lost that sense of a larger unity. Why? Rauch cites many reasons, including these:

“The declining hold of organized religion and especially the collapse of mainline Protestant denominations have displaced apocalyptic and redemptive impulses into politics, where they don’t belong. Identity politics on the left and market fundamentalism on the right erode the feeling of shared citizenship and identity. . . .The fragmenting of media isolates us in our separate information bubbles. Algorithmic social-media platforms provide a lucrative business model for viral outrage. “

Furthermore, we had built defenses against tribalism–the rule of law, the Constitution, political parties, social institutions–but now all of those have eroded:

“In civic life, we have succumbed to — in fact, we have valorized — cynicism about core institutions. In education, elite universities frequently encourage students to burrow into their tribal identities rather than transcend them. In media, new technologies enable and monetize outrage and extremism. In the realm of social mores, norms like forbearance, truth-telling, and respect for law have come under attack. . . .

The founders were well aware of the dangers of populism, demagoguery, and faction. They built a constitutional order designed to force compromise and impede sociopathic behavior. But the institutions they put in place to act as gatekeepers (the Electoral College, the appointed Senate) became obsolete, and the successor gatekeepers (political bosses, smoke-filled rooms, big media) came to seem undemocratic and lost their grip.

What can be done? Rauch agrees with the conservative thinker Yuval Levin on the need to rebuild institutions. Rauch quotes Levin:

What does stand out about our time…is not the strength of these pressures but the weakness of our institutions — from the family on up through the national government with lots in between — which leaves us less able to handle the pressures and to hold together. And it leaves us with something more like formless connectedness, a social life without structural supports, which can work fine for people with lots of social capital to spend but doesn’t work nearly as well for those who need to build their stock of it.

Rauch comments, “Rebuilding institutions — and, just as important, noticing and valuing them — is more important for containing tribalism than pretty much anything that public policy could do. And two institutions in particular deserve strengthening: the Republican Party and the Democratic Party.”

This will no doubt seem strange. Aren’t the parties, almost by definition, the very font of partisan polarization? Actually, no. Paradoxically, partisanship has never been stronger, but the party organizations have never been weaker — and this is not a paradox at all. When they had the capacity to do so, party organizations engaged citizens in volunteer work, local party clubs, and social events, giving ordinary people a sense of political engagement that merely voting or writing a check cannot provide. Until they lost the power to do so, they road-tested and vetted political candidates, screening out incompetents, sociopaths, and those with no interest in governing. When they could, they used incentives like jobs, money, and protection from primary challenges to get legislators to work together and accept tough compromises. Perversely, the weakening of parties as organizations has led individuals to coalesce instead around parties as brands, turning organizational politics into identity politics.

To put the point another way, the more parties weaken as institutions, whose members are united by loyalty to their organization, the more they strengthen as tribes, whose members are united by hostility to their enemy (whether real, exaggerated, or invented). In that respect, polarization is called upon to provide solidarity when institutions cannot.

I think ideology is more important than Rauch thinks it is–specifically, the ideology surrounding life issues. There is a chasm between those who believe there is nothing wrong with abortion and those who believe it takes the life of a child. Secular observers think this is just one opinion among many, but this makes them blind to its existential importance for both sides. At stake also in this issue for pro-abortion advocates is feminism and the sexual revolution. For pro-lifers, the issue also touches on the nature of sexuality, the protection of the family, and the value of life itself. For both sides, this “ideological” issue is also emotional, and rightly so.

Still, I think Rauch is onto something. He thinks that once we are aware of the problem–and many Americans are complaining about the symptoms–we can rebuild the safeguards against tribalism. These include, interestingly, preserving the Electoral College (which Democratic candidates are seeking to abolish) and bringing back the “smoke-filled rooms” of the political parties (an “establishment” that both sides have condemned in favor of primary elections, which provide “greater democracy”). More fundamentally, though, by his own logic, we need to recover the centrality of institutions such as the family and the church.

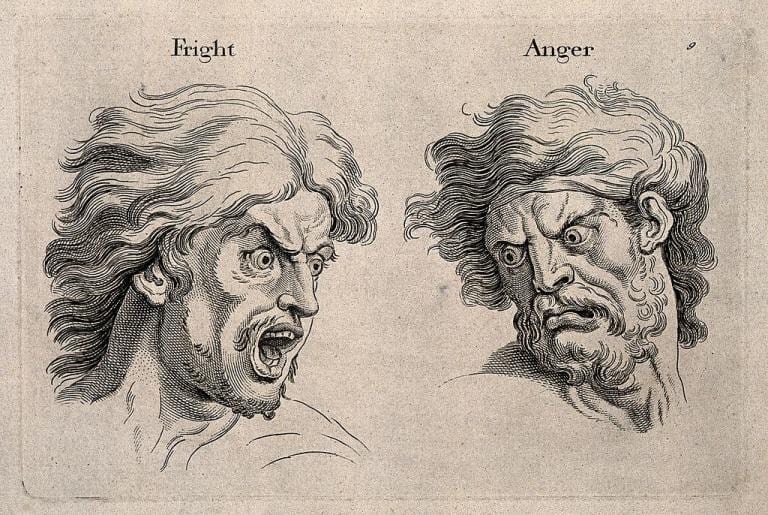

Illustration: A frightened and an angry face,c. 1760, after C. Le Brun [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)] via Wikimedia Commons