How is it that moral relativists–those who don’t believe in moral absolutes, who think morality is a cultural or individual construction, who reject traditional morality–are nevertheless so moralistic? Moral relativists today are so judgmental, so pre-occupied with virtue signaling, so unforgiving, so self-righteous? How can that be?

Well, a friend and former colleague of mine, Mark Mitchell offers an answer in his new book Power and Purity: The Unholy Marriage That Spawned America’s Social Justice Warriors. He argues that what we are seeing among the “woke” in academia, politics, and social media is the unstable coming together of two ultimately incompatible worldviews and strains of thought: That of Nietzsche and that of the Puritans.

Nietzsche, the key philosopher of postmodernism, maintained that morality, reason, and every institution of civilization have no objective basis, that they are not nothing more than manifestations of the will to power. Indeed, the desire for power over other people is the primary psychological motivation for everyone. Marx would apply this maxim to socio-economic classes, saying that cultural expressions and practices are the means for the ruling class to exert power over those it oppresses. Then the post-Marxists of today apply that principle, that everything can be reduced to power and that power is always oppressive, to other groups–those of race, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, species, etc., etc.–in which the privileged (white, male, heterosexual, rich, human) exercise power over the marginalized (racial minorities, women, LBTQ, the poor, animals).

But we also have a heritage of Puritanism, which insists on moral purity and strict social controls against moral transgressions. This attitude has continued even among those who reject the Christianity that the original Puritans adhered to and that made their moral rigor ultimately benevolent. The actual Puritans were mostly Calvinists, who–despite their quest for moral purity–emphasized that they were saved by God’s grace, not by their works, and that there is forgiveness for those who are morally depraved. In today’s secularized Puritanism, of course, which excludes God, sinners must repent, but there is no mechanism for redemption, neither from Christ nor from the repentant sinner, and so there is no forgiveness.

The Puritans had a “great Awakening,” which brought the Gospel to those already highly conscious of their failure to keep the Law they believed in so earnestly. Today we have what could be called a “great Awokening,” in which a secularized Puritanism is joined to a Nietzschean view of culture. Power is everywhere. But power, by the canons of the new Puritanism–which, like the old, values freedom, condemns oppression, and has a revolutionary zeal–is evil. So it must everywhere be condemned.

That’s my summary of Dr. Mitchell’s main argument, which he develops in greater detail and at a higher level of sophistication. Here is what I said in a blurb I wrote for his book:

Why is it that postmodernists who believe there are no moral absolutes are so moralistic? Why have universities replaced rational discourse with silencing and punishing those who hold dissident ideas? Why is identity politics so vicious? Having read Mark Mitchell’s Power and Purity, now I know.

The seminal thinker for our day is Friedrich Nietzsche, who reduces all of culture, ideas, and life itself to the will to power. Mitchell unpacks both Nietzsche’s influence and his predictions.

And yet few people—for now—follow his moral nihilism, with even the hard left upholding values Nietzsche despised, such as equality and compassion. The Christian influence remains, even for those who believe with Nietzsche that God is dead. In fact, the left is employing a mash-up of Nietzsche and a secularized Puritanism, which has rejected God while cultivating self-righteousness and the zeal to censor, control, and punish.

This book, which combines scholarly depth and a lively, readable style, will help readers navigate the strange paradoxes of contemporary politics, academia, and culture.

Dr. Mitchell stresses that Nietzsche and moral Puritanism are ultimately incompatible. Today’s woke moralists, to their credit, still believe in compassion, mercy, and help for the downtrodden. But Nietzsche, who celebrated the strong’s dominance over the weak, despised those values. He hated Christianity not because it was oppressive but precisely because it condemned oppression, demanding mercy for the poor, the weak, and the socially marginalized.

Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity was that it was the “revolt of the slaves,” a way to make the powerful feel guilty for their power. In ancient Rome, he said, Christianity was the religion of slaves, women, and other powerless groups, and when Christianity triumphed, this new religion–with its ethic of love, which practiced pity for the weak and the diseased, rather than letting them die out–fulfilled the will to power of the weak over the strong.

The benevolent ethics of the “woke” crusaders cannot be sustained by their Nietzschean worldview. If they want compassion, they must find a different basis, such as Christianity. If they want power, they will become the mirror image of those whom they now condemn.

What happens when those who believe that power is always oppressive achieve power for themselves? They will tend to be oppressive. Which is why we should never vote for someone who thinks that way.

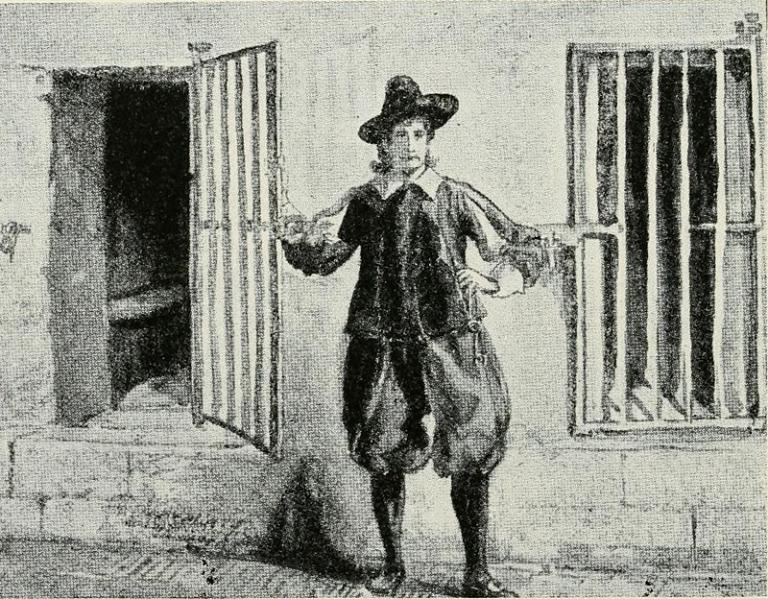

Image from page 195 of “History of the Pilgrims and Puritans, their ancestry and descendants; basis of Americanization” (1922) via Flickr, no known copyright restriction.