The COVID-19 epidemic, now on the upswing again, keeps raising baffling questions: Why do some people get it and others don’t? Why is it relatively harmless to some people while deadly to others? Do anti-bodies really not last, and what does that mean for acquiring immunity? Why does the disease attack certain organs, like the spleen, the way it does?

In trying to answer to those questions, scientists are discovering new aspects of the body’s immune system when it comes to COVID-19: specifically, the role not just of antibodies but of T cells.

And what they are finding is encouraging, both for immunity to the disease and the prospect of an effective vaccine.

I came across a fascinating article from BBC that tells all about it. Here is the opening, but you’ll want to read it all. From Zaria Gorvett, The people with hidden immunity against Covid-19 on the BBC website [my bolds]:

The clues have been mounting for a while. First, scientists discovered patients who had recovered from infection with Covid-19, but mysteriously didn’t have any antibodies against it. Next it emerged that this might be the case for a significant number of people. Then came the finding that many of those who do develop antibodies seem to lose them again after just a few months.

In short, though antibodies have proved invaluable for tracking the spread of the pandemic, they might not have the leading role in immunity that we once thought. If we are going to acquire long-term protection, it looks increasingly like it might have to come from somewhere else.

But while the world has been preoccupied with antibodies, researchers have started to realise that there might be another form of immunity – one which, in some cases, has been lurking undetected in the body for years. An enigmatic type of white blood cell is gaining prominence. And though it hasn’t previously featured heavily in the public consciousness, it may well prove to be crucial in our fight against Covid-19. This could be the T cell’s big moment.

T cells are a kind of immune cell, whose main purpose is to identify and kill invading pathogens or infected cells. It does this using proteins on its surface, which can bind to proteins on the surface of these imposters. Each T cell is highly specific – there are trillions of possible versions of these surface proteins, which can each recognise a different target. Because T cells can hang around in the blood for years after an infection, they also contribute to the immune system’s “long-term memory” and allow it to mount a faster and more effective response when it’s exposed to an old foe.

Several studies have shown that people infected with Covid-19 tend to have T cells that can target the virus, regardless of whether they have experienced symptoms. So far, so normal. But scientists have also recently discovered that some people can test negative for antibodies against Covid-19 and positive for T cells that can identify the virus. This has led to suspicions that some level of immunity against the disease might be twice as common as was previously thought.

Most bizarrely of all, when researchers tested blood samples taken years before the pandemic started, they found T cells which were specifically tailored to detect proteins on the surface of Covid-19. This suggests that some people already had a pre-existing degree of resistance against the virus before it ever infected a human. And it appears to be surprisingly prevalent: 40-60% of unexposed individuals had these cells.

As the article explains, some people may have developed these anti-coronavirus T cells from life-long experiences with the common cold, which comes from a virus that also has those spike-like surfaces like COVID-19.

As people get older, their production of T cells goes down, which can help explain why older folks are more at risk for contracting the virus.

While T cells can confer immunity, likely long-term immunity, to COVID-19, when a non-immune person does get a serious case of the disease, it attacks the T cell system–including the spleen–making the immune system go berserk, attacking healthy cells and leading to death.

The good news is that vaccines–including at least some of the ones currently in trial–can successfully be a catalyst for the production of the T cells that we need.

We are fearfully and wonderfully made (Psalm 139:14).

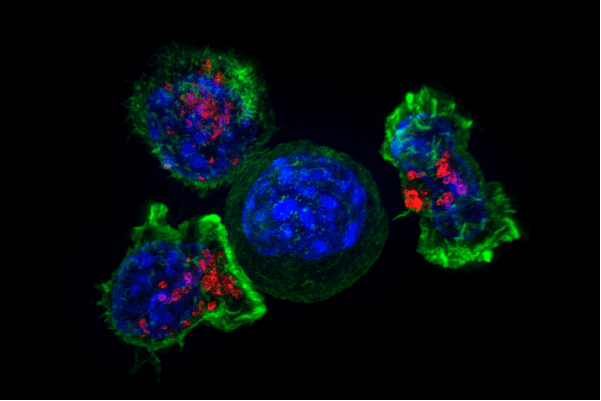

Illustration: Super-resolution image of T cells attacking a cancer cell, from the National Institute of Health via Flickr, Public Domain. Credit: Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz and Gillian Griffiths, National Institutes of Health. The caption is instructive:

Superresolution image of a group of killer T cells (green and red) surrounding a cancer cell (blue, center). When a killer T cell makes contact with a target cell, the killer cell attaches and spreads over the dangerous target. The killer cell then uses special chemicals housed in vesicles (red) to deliver the killing blow. This event has thus been nicknamed “the kiss of death”. After the target cell is killed, the killer T cells move on to find the next victim.