The senior curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art gave a presentation on his plans to diversify the collection by seeking out more art by women and minorities. He concluded his talk by remarking, “don’t worry, we will definitely still continue to collect white artists.” For saying that, he was branded a “white supremacist.” He lost his job.

A few weeks ago, an editor at the New York Times lost his job not for his own opinions but for allowing a conservative U.S. senator to express his opinions on the op-ed page.

Now another New York Times opinions editor, Bari Weiss, has resigned, due to harassment from colleagues who are attacking her for being “centrist.” From her resignation letter:

My own forays into Wrongthink have made me the subject of constant bullying by colleagues who disagree with my views. They have called me a Nazi and a racist; I have learned to brush off comments about how I’m “writing about the Jews again.” Several colleagues perceived to be friendly with me were badgered by coworkers. My work and my character are openly demeaned on company-wide Slack channels where masthead editors regularly weigh in. There, some coworkers insist I need to be rooted out if this company is to be a truly “inclusive” one, while others post ax emojis next to my name. Still other New York Times employees publicly smear me as a liar and a bigot on Twitter with no fear that harassing me will be met with appropriate action. They never are.

There are terms for all of this: unlawful discrimination, hostile work environment, and constructive discharge. I’m no legal expert. But I know that this is wrong.

She asks the publisher, to whom her letter is addressed, how he could let this happen. She says that she is convinced that most employees at the Times are not like this, but that they are cowed into submission and silence. She castigates the prevailing mindset as violating the very nature of journalism. She cites the lessons of the 2016 election, in which the nation’s leading newspaper was taken completely by surprised by the election of Donald Trump, whose supporters the paper takes no interest in trying to understand. She writes,

But the lessons that ought to have followed the election — lessons about the importance of understanding other Americans, the necessity of resisting tribalism, and the centrality of the free exchange of ideas to a democratic society — have not been learned. Instead, a new consensus has emerged in the press, but perhaps especially at this paper: that truth isn’t a process of collective discovery, but an orthodoxy already known to an enlightened few whose job is to inform everyone else.

Some prominent liberals and progressives have concluded that the cancel culture has gone too far, and 150 of them have affixed their names to “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” published in Harper’s Magazine. After the obligatory denunciation of President Trump and the

“illiberal,” “intolerant” climate associated with him, the letter says that we on the other side must not become illiberal and intolerant ourselves (my bolds):

The free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, is daily becoming more constricted. While we have come to expect this on the radical right, censoriousness is also spreading more widely in our culture: an intolerance of opposing views, a vogue for public shaming and ostracism, and the tendency to dissolve complex policy issues in a blinding moral certainty. We uphold the value of robust and even caustic counter-speech from all quarters. But it is now all too common to hear calls for swift and severe retribution in response to perceived transgressions of speech and thought. More troubling still, institutional leaders, in a spirit of panicked damage control, are delivering hasty and disproportionate punishments instead of considered reforms. Editors are fired for running controversial pieces; books are withdrawn for alleged inauthenticity; journalists are barred from writing on certain topics; professors are investigated for quoting works of literature in class; a researcher is fired for circulating a peer-reviewed academic study; and the heads of organizations are ousted for what are sometimes just clumsy mistakes. Whatever the arguments around each particular incident, the result has been to steadily narrow the boundaries of what can be said without the threat of reprisal. We are already paying the price in greater risk aversion among writers, artists, and journalists who fear for their livelihoods if they depart from the consensus, or even lack sufficient zeal in agreement.

The list of signatories includes feminist icon Gloria Steinem, the pioneering linguist and hard-left activist Noam Chomsky, the Handmaid’s Tale author Margaret Atwood, the Islamic fatwa target Salman Rushdie, the author of the Harry Potter books J. K. Rowling.

The reaction? Social media wrath, indignation from other prominent progressives, and cancel culture outrage! Which, of course, prove the letter’s point.

The signers who had impeccable progressive credentials were nevertheless pilloried for their guilt by association. Signers of the letter should be punished, some said, not so much for their opinions but for the opinions of the other signers. Some of these people who signed this document–for example, J. K. Rowling–have said that men who identify as women are still men! Such “transphobia,” said one trans individual, “makes me feel less safe.” Another attacker said, “i really wonder if some of the people who signed this thought long and hard about whose names they’d appear next to.” At least one signer retracted her signature and abjectly crumbled when faced with the behavior she had just criticized. “I did not know who else had signed that letter,” she said. “I thought I was endorsing a well meaning, if vague, message against internet shaming. I did know Chomsky, Steinem, and Atwood were in, and I thought, good company. The consequences are mine to bear. I am so sorry.” She wanted to associate with that “good company,” not a bad person like the author of the Harry Potter books!

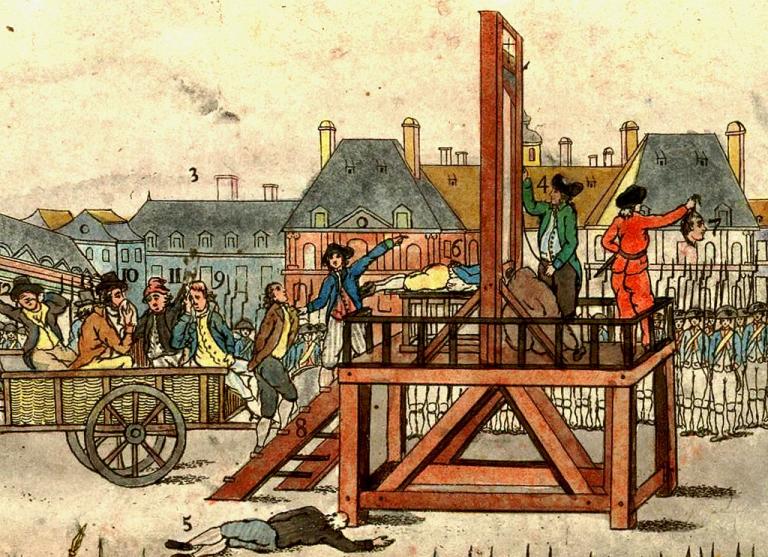

Robby Soave in Reason Magazine, notes the repeated theme in such cancelation frenzies of people “not feeling safe” when certain ideas are stated, as if speech were a type of violence. The invocations of “safety” remind him of the Committee of Public Safety, which took charge of the French Revolution in 1793. In the name of “safety,” the committee launched the reign of terror, which swept up those accused by the mob and sent them without trial to the guillotine. Things aren’t that bad, of course, Soave says, but the mindset is instructive. He calls it the 1793 Project.

I would add that Robespierre, who led the Committee of Public Safety, became a victim of the frenzy that he himself unleashed, as his fellow Jacobins turned on each other for alleged lapses of ideological purity. Robespierre’s head ended up in the same basket as the monarchists and Christians he had guillotined.

Something similar happened in the Russian revolution with the assassination of Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky and in the Chinese cultural revolution with the Red Guard purges of Communist party officials who were deemed not radical enough.

Again, we are nowhere near that revolutionary dynamic in which the revolutionaries start destroying each other. But there is a lesson here for progressives, as well as conservatives and everyone else. As Christians know, no one can pass a purity test.

Illustration: “The Execution of Robespierre,” by Unknown author / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons