What is a citizen? A rational, self-governing individual, so that the political task consists largely of debate and persuasion? Or a potential victim whom the government must protect from harm by imposing controls?

According to Matthew Crawford, we have drifted to that latter conception of the role of citizens and the role of government. In his essay Covid Was Liberalism’s Endgame, he argues that the pandemic exposed the weakened state of liberal democracy and, indeed, may have brought it to an end.

Please, read it all. Here are some samples:

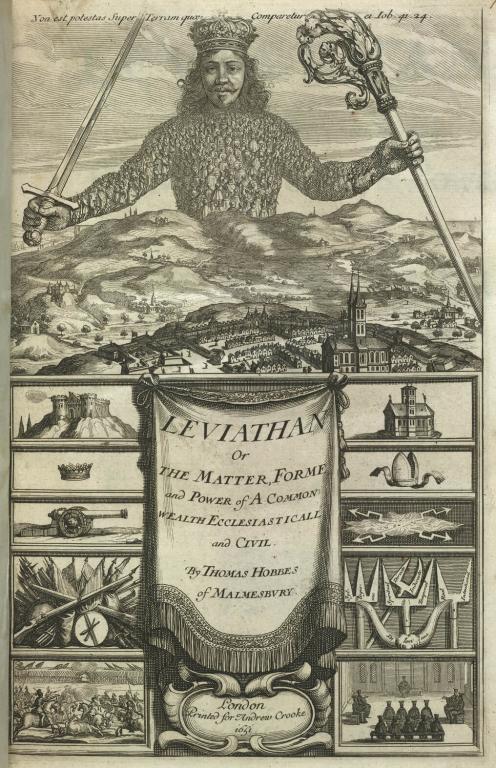

Our regime is founded on two rival pictures of the human subject. The Lockean one regards us as rational, self-governing creatures. It locates reason in a common human endowment — common sense, more or less — and underwrites a basically democratic or majoritarian form of politics. There are no secrets to governing. The second, rival picture insists we are irrationally proud, and in need of being governed. This Hobbesian picture is more hortatory than the first; it needs us to think of ourselves as vulnerable, so the state can play the role of saving us. It underwrites a technocratic, progressive form of politics.

The Lockean assumption has been quietly put to bed over the last 30 years, and we have fully embraced the Hobbesian alternative.

The Nineties saw the rise of new currents in the social sciences that emphasise the cognitive incompetence of human beings, deposing the “rational actor” model of human behaviour. This gave us nudge theory, a way to alter people’s behaviour without having to persuade them of anything. . . .

This is one front in a larger development: an intensifying distrust of human judgment when it operates in the wild, unsupervised. Sometimes this takes the purely bureaucratic form of insisting on metrics of performance and imposing uniform procedures on professionals. “Evidence-based medicine” circumscribes the discretion of doctors; standardised tests and curricula do the same for teachers. At other times, this same impulse takes a technological form, with algorithms substituting for individual judgment on the grounds that human rationality is the weak link in the system. For example, it is stipulated that human beings are terrible drivers and must be replaced in a new regime of autonomous vehicles. The effect, consistently, is to remove agency from skilled practitioners on the grounds of incompetence, and devolve power upward toward a separate layer of information managers that grows ever thicker. . . .

In 2020, a fearful public acquiesced to an extraordinary extension of expert jurisdiction over every domain of life, and a corresponding transfer of sovereignty from representative bodies to unelected agencies located in the executive branch of government. Notoriously, polling indicated that perception of the risks of Covid outstripped the reality by one to two orders of magnitude, but with a sharp demarcation: the hundredfold distortion was among self-identified liberal Democrats, that is, those whose yard signs exhorted us to “believe in science.”

In a technocratic regime, whoever controls what Science Says controls the state. What Science Says is then subject to political contest, and subject to capture by whoever funds it. Which turns out to be the state itself. Here is an epistemic self-licking ice cream cone that bristles at outside interference. Many factual ambiguities and rival hypotheses about the pandemic, typical of the scientific process, were resolved not by rational debate but by intimidation, with heavy use of the term “disinformation” and attendant enforcement by social media companies acting as franchisees of the state. In this there seems to have been a consistent bias toward scientific interpretations that induced fear, even at the cost of omitting relevant context.

He says much more, covering also “moral emergencies,” “victim dramas,” and how the COVID lockdowns worked to create “social distance” from intermediary institutions and relationships, leaving only dependence on the state. Again, you’ve got to read it all.

Although Crawford describes liberal Democrats as the most in thrall to this way of thinking, he suggests that conservatives too have fallen into this “Hobbesian” view of citizenship and government. Conservatives also appeal to our sense of vulnerability and victimhood and promises to relieve our fears by state action. And much Republican rhetoric also seeks to “nudge” voters rather than persuade them.

Some fears are surely legitimate, though. What conservatives are mostly afraid of is precisely the intrusive and paternalistic state: that it will persecute our religion, corrupt our children, take our guns, and destroy our economy.

One could argue that a Biblical view of government suggests that we are not as rational as Locke assumed and that Hobbes had a point (Romans 13:1-7; 1 Peter 2:13-17). But punishing evildoers so as to allow those who do well to flourish ascribes a fairly minimalistic role to government compared to the all-encompassing Leviathan advocated by Hobbes and put into practice by politicians today.

What do you think of Crawford’s concerns?

Illustration: Title Page of Thomas Hobbes’ “Leviathan” (1651), British Library, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons