You may have heard that the Supreme Court sided with the football coach who lost his job for praying on the field. What you may not have heard is that, in doing so, the court overturned a restrictive ruling on church/state relations from two decades ago and created new standards for religious liberty cases.

The case, Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, involved a football coach in Washington State, Joseph Kennedy, who had the personal custom of going to the middle of the field and praying after each game. Some players and other students, of their own volition, would join him. The school board believed this constituted an establishment of religion and refused to renew his contract.

Lower courts agreed that the coach was violating the Establishment Clause, but the Supreme Court ruled otherwise by a 6-3 vote. Neil Gorsuch, who wrote the majority opinion, said that the school board action “rested on a mistaken view that it had a duty to ferret out and suppress religious observances even as it allows comparable secular speech.” On the contrary, the government should not “be hostile” to religion.

The bottom line, according to the Wikipedia article on the ruling, is that the government “may not suppress an individual from engaging in personal religious observance.”

That alone would be a landmark ruling for religious liberty. But the court didn’t stop there. Just as it over-ruled Roe v. Wade, it over-ruled another Supreme Court decision from the 1970s, Lemon v. Kurtzman. That 1971 case struck down a Pennsylvania law that would allow state funds to pay parochial school teachers who used public school material and didn’t teach religion. In the course of that ruling–which sounds right to me, since the law would have a secularizing effect on church-related schools–the court set forth three criteria for legislation that touches on religion, the so-called “Lemon test”:

These standards are very difficult to interpret and apply, and subsequent Supreme Courts have sought to define and refine them further. But in Kennedy v. Bremerton, the justices threw them out altogether. Though the ruling wasn’t completely thrown out–Pennsylvania still can’t pay parochial school teachers–the ruling instructed lower courts not to use the “Lemon test” anymore. “In place of Lemon,” the court ruled, “the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by reference to historical practices and understandings.”

Arguably, that too may be challenging to define and apply, but it fits the originalist judicial philosophy that now prevails on the court. And it does not give a blank check for religious litigants. In the original Pennsylvania case, reference to historical understandings would reveal that parochial school teachers were always expected to provide a distinctly Christian education, as distinct from the public schools. So a law co-opting them into the public system would still be impermissible.

For an illuminating discussion of the implications of this new ruling, see When the Court Takes Away Lemon: What the Praying Coach Ruling Means for Religious Americans by Howard Slugh, the General Counsel of the Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty. Here is how he summarizes what it means for religious liberty:

It is safe to say that some of the most anti-religious understandings of Lemon are no longer tenable.

For example, a public school does not violate the Establishment Clause by merely failing to censor private religious speech. The Court went further and explained that under this test, it is clear that that the Establishment Clause does not “compel the government to purge from the public sphere anything an objective observer could reasonably infer endorses religion.”

Under this new test, state actors no longer need to worry about unpredictable litigation brought by their most zealously anti-religious citizens. No city has any reason to fear allowing a rabbi to place a menorah in a park, and no school has a reason to fear allowing a Jewish, Muslim, Christian, or any other religious teacher to express her faith in front of her students.

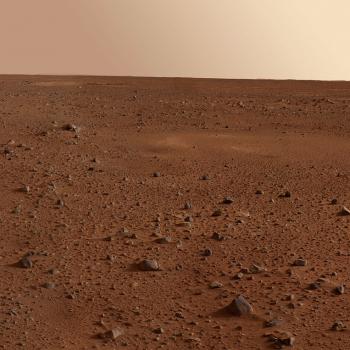

Photo: Supreme Court building by Joe Ravi, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16959908