The 18th century British statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke, considered the father of modern conservatism, observed that political religion has “no efficacy,” even to do what it intends. But transcendent religions do have “efficacy.” Though this is not their focus, they even have political efficacy, since they force human beings and their institutions to be humble, which is a prerequisite for ordered liberty.

Thanks to John G. Grove for bringing out Burke’s thoughts in his Law & Liberty article A “Religion of No Efficacy”.

He begins by citing a short statement in Burke’s notebook from the first two years of his coming to England from Ireland, which was first published in the 20th century:

If you attempt to make the end of Religion to be its Utility to human Society, to make it only a sort of supplement to the Law, and insist principally upon this topic, as is very common to do, you then change its principle of Operation, which consists on Views beyond this Life, to a consideration of another kind, and of an inferior kind.

Grove then unpacks that statement with the help of other writings from Burke. Here are some quotations from Burke, with summaries and commentary from Grove:

The social benefits of religion come precisely because it is something that transcends the political, and they depend on the manner in which religion is approached by the people. When we come to think that eternal rewards and punishments are aimed primarily at the immediate, political “purposes of a moment,” they become less impressive to us: “We cool immediately, the Springs are seen; we value ourselves on the Discovery; we cast Religion to the Vulgar and lose all restraint.”

As has happened today, with the politicization of religion, first from the Left in mainline evangelicalism and now from the Right, with Christian nationalist evangelicals.

People see religion as just a way to enforce political control and thus discount it. In contrast, a transcendent religion, focused not on “utility to society” but on eternity and an infinite, supernatural God, has a different effect:

Placing all human endeavors next to the sublimity of God, as he noted in his Philosophical Enquiry, has the effect of diminishing our opinion of ourselves and our capabilities: “Whilst we contemplate so vast an object, under the arm, as it were, of almighty power, and invested upon every side with omnipresence, we shrink into the minuteness of our own nature, and are, in a manner, annihilated before him.”

This mindset is important both for the people and their political leaders:

Religion, then, could have the effect of dampening experimental and revolutionary fervor—what reader of the Book of Job, for instance, could ever dare to say that “we have it in our power to begin the world over again”? If political authority is seen as part of God’s providential order, we will “look with horror on those children of their country who are prompt rashly to hack that aged parent to pieces, and put him into the kettle of magicians.”

But importantly, it also ought to have the same humbling effect on those who exercise that political authority: “All persons possessing any portion of power ought to be strongly and awefully impressed with an idea that they act in trust; and that they are to account for their conduct in that trust to the one great master, author and founder of society.” This manifested in “politic caution” and a “moral timidity” (hardly the language of today’s politics) when pursuing any great political undertaking. The one who exercises power must even “fear himself.”

Grove summarizes Burke’s point: “The political benefits of religion, then, rely on the humility that true religion ought to produce. And, as the young Burke suggested, it could only come as a side effect of a religion that was not focused primarily on political and social affairs.”

Read the whole article. In our current debates about the relationship between Christianity and politics, we need to understand what Burke was saying and to see how his insights have been borne out in history. A politicized religion, almost by definition, is a secularized religion. We see this in the effect of liberal theology with its “social gospel” on mainline Protestantism, which has shrunk to irrelevance even as it eagerly adopts every secularist cause. This is also what has happened to the state churches of Europe.

What makes Christian nationalist evangelicals, Catholic integralists, Reformed theonomists, and Pentecostal dominionists think that an established church that rules society would fare any better? There can be a secularism of the Right, as well as a secularism of the Left.

Whereas the true church consists of people “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages. . . crying out with a loud voice, ‘Salvation belongs to our God who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb!’” (Revelation 7: 9-10). And, ironically, that kind of church will have the biggest positive impact on society.

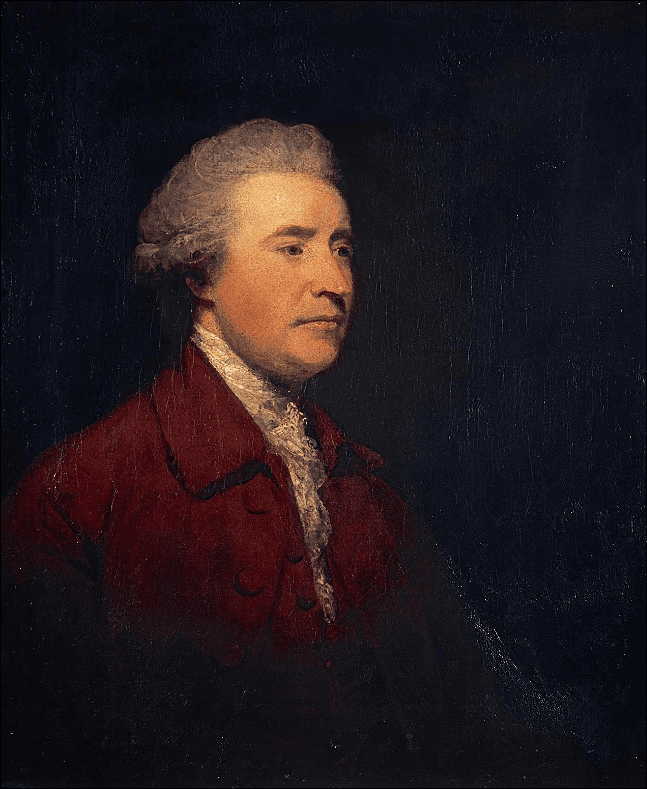

Illustration: Portrait of Sir Edmund Burke (1750) by Sir Joshua Reynolds via Picryl, Public Domain