The Orthodox have a rich theological and spiritual tradition, much of which–but not all– we Lutherans would disagree with. They are very sacramental, but they also value monasticism and asceticism, the strict disciplines of fasting and self-denial.

So I was intrigued to stumble across an article in the Acton Institute’s Religion & Liberty that relates the sacraments to what we Lutherans would recognize as vocation. And key to this is a certain understanding of asceticism.

The article is An Ascetic Way of Life in a World of Abundance by Dylan Pahman. Here is the pull-out summary:

Christians are called to feast on God so they may be ready to pursue their vocations and serve their neighbors. That often requires an ascetic discipline that is in conflict with Western abundance.

Pahman draws on the Orthodox priest and theologian Alexander Schmemann. and what he developed in his book For the Life of the World (which is also the name of the magazine of Concordia Theological Seminary, so there must be Lutheran value in it) as his “liturgical worldview.”

As for the details of this Orthodox liturgical worldview, drawing on the story of Paradise in Genesis 2, Schmemann focuses on eating: “Man is a hungry being. But he is hungry for God. Behind all the hunger of our life is God. All desire is finally a desire for Him.” . . .

All this relates to our everyday, economic life. It guards us against gnosticism, which claims that the material world, and thus material wealth, is inherently evil. Second, it also guards against hedonism and greed, reshaping our consumption of the world. “It is not accidental,” writes Schmemann, “that the biblical story of the Fall is centered again on food. … Not given, not blessed by God, it was food whose eating was condemned to be communion with itself alone, and not with God. It is the image of the world loved for itself, and eating it is the image of life understood as an end in itself.”

This is to say, our need for food takes us into the economic realm. Eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil caused our Fall. Eating the Sacrament of Christ’s body hung on the tree of the Cross is to eat of the Tree of Life (my parallel, not Pahman’s or Schmemann’s, but I think it makes their point).

And the eating we need to do to keep ourselves alive is made possible by our economic vocations. Those also require that we submit to one of the curses of the Fall: “By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread” (Genesis 3:29). Jesus Himself refused to sidestep that curse in His temptation by the devil in the wilderness, which as Milton shows us is Christ’s undoing of the sin of Adam. Pahman quotes another Orthodox theologian, Paul Evdokimov: “To transform stones into bread is to solve the economic problem, to suppress ‘the sweat of one’s brow,’ to eliminate all ascetic efforts, and creation itself.”

Evdokimov then applies this principle to society and to vocation:

Indeed, we should not seek purely external substitutes or magical, utopian plans for what can only be accomplished through ascetic effort or love, and we absolutely should ascetically transform our labor and economic consumption from the inside out.

So our need to eat our bread in the sweat of our brows, the need to sometimes eat and sometimes not eat, the need to control our appetites for both food and other things, the need to work hard, brings us to asceticism.

Evdokimov calls for the monastic ascetic disciplines to have a counterpart in the lives of all Christians.

Indeed, it is through the everyday asceticism of what Evdokimov called “interiorized monasticism” that even those of us living “in the world” can face our unique challenges today. “The monasticism that was entirely centered on the last things formerly changed the face of the world,” he writes. “Today it makes an appeal to all, to the laity as well as to the monastics, and it points out a universal vocation. For each, it is a question of adaptation, of a personal equivalent of the monastic vows.” He intriguingly recommends that everyone appropriate the disciplines of poverty, chastity, and obedience, which he labels “a great charter of human liberty.”

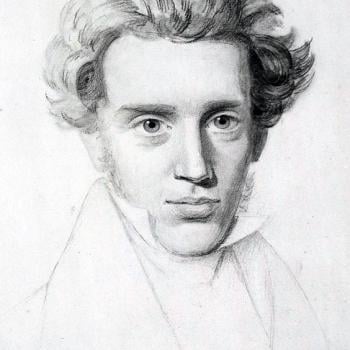

Luther shows us exactly how that can be done. As Swedish theologian Einar Billing pointed out, Luther moved those “spiritual disciplines” out of the monastery and into the vocations of secular life. Poverty became thrift and hard work, the discipline of paying bills and trying to make ends meet. Chastity became faithfulness in marriage. Obedience became submission to the law. Furthermore, the monastic practices of prayer, meditation, and worship–while still central to every Christian’s vocation in the Church—also moved into the family and the workplace.

[See Einar Billing, Our Calling (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1964), p. 30. This classic treatment of vocation is out of print, but go here for a free online text.]

Pahman’s discussion is complex and I am simplifying it in a Lutheran direction. I question his and the orthodox theologians’ arguments that the sacraments make everything sacramental. If everything is sacramental, what is so special about the Lord’s Supper and Baptism? Of course, though, God’s use of the physical realm, which He created and into which He was incarnate, to reach us physical beings sanctions the Christian’s vocations, which involve us in the physical, not just the spiritual, realm.

And I question the premium this article puts on monasticism and asceticism, since I see their value primarily in the Lutheran sense that Billing describes.

But Pahman’s article and the theologians he cites have much to offer. Not that they are purposefully drawing on Luther. But when the parallels are close, it is evident that both the Lutherans and the Orthodox are simply working out the logic of the Christian life.

The article also includes a great quote: “As St. Justin Martyr put it: ‘To God nothing is secular, not even the world itself, for it is His workmanship.’”

And a great anecdote:

In his book Everyday Saints, Archimandrite Tikhon recounts a story told to him by a priest about life in the Gulag:

Many priests knew the text of the Liturgy by heart. We could find bread even if it wasn’t wheat bread, usually without difficulty. We had no choice but to replace the wine with cranberry juice. Instead of the altar with the relics of the martyr on which Church rules require us to serve the Liturgy, we would get the fellow convict-priest among us who had the broadest shoulders to help us. He would strip to his waist, lie down, and then we would say the Divine Liturgy upon his chest.

In extreme circumstances, a man himself can literally be Christ’s holy altar. This altar, too, contained holy relics—the bones of the “convict-priest.”

Photo: Fr. Alexander Schmemann by https://www.schmemann.org/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=142163762