If we are moving into a post-secular era, a broad-based recovery of religion in society, we mustn’t assume that this will necessarily be Christian, as such. We can hope that it will be, but if it isn’t, what kind of religion might it be?

My fellow Patheos blogger Anthony Costello had an interesting post a few months ago that can help us think through the different kinds of religious expression:

Ever since Panaetius of Rhodes (185-110/109 BC) philosophers have recognized three modes of theological expression. These are: the poetic, the philosophic and the political. I have written in detail about each here. In brief, the poetic relates to the imaginative aspect of man’s thoughts about god, those that speak most powerfully to man’s existential concerns: meaning, purpose, and value. Consider Jordan Peterson as an example of someone who thinks about God, or god, in this mode. The philosophic mode deals primarily with our metaphysical and epistemic concerns. It considers what is or is not real, what can be shown or demonstrated to be true, and what are our moral obligations given those realities and truths. William Lane Craig or Richard Swinburne would be good examples of this kind of thinker.

Finally, there is the political, or civic, mode of theology, that “which maintains the traditional cult and is indispensable for public education.” (Copleston, A History of Philosophy Vol 1., 422). The political expression of theological ideas does not discount either of the other forms. But its chief aim is to organize society and see that it functions properly. This is given the societal fact that man is an inherently religious creature. Man is homo religiosus, or, homo credens, who knows intuitively that his social dealings must be grounded in something divine, something god-like.

Panaetius, of course, was thinking in terms of Greco-Roman paganism. There were the myths, the wonderful tales of gods and goddesses that sometimes conveyed profound meanings. They address the imagination, which can often resonate deeply into the human heart. That would be the poetic approach to religion.

Then there were the philosophers who reflected on the universe and what it means, including the reality of God. Socrates argued that the myths about the gods could not be true because they often act worse than mortals do. The true God must be righteous. Aristotle argued that there must only be one God who transcends this physical realm, though since he must be complete in himself, he would take no interest and have no involvement with mortals. These thinkers address the reason. This is the philosophic approach to religion.

Then there was the public cult, the rituals of supplication and sacrifice to the gods that were an important, unifying function to Greco-Roman society. This civil religion held the nations and city states together, sanctifying the culture, giving divine sanction to the political order, and promoting good citizenship. The priests of the official cult addressed the social good.

If we accept this classification, even though it comes out of pre-Christian religion, we can see that Christianity can contain them all. The narratives of Scripture, the experience of the saints of yesterday and today, the rich heritage of Christian art, literature, and music, all these exemplify the poetic mode. Christianity also has its theologians, apologists, scholars, and thinkers all of whom employ the philosophic mode. And Christianity has always influenced the culture and promoted social morality. This would be the political mode.

But Panaetius was not finished. He believed that the political is the only mode of religion that has any relevance. This is because he was a Stoic. Consider today’s topic a sequel to our recent post The Stoic Revival.

In Costello’s more extensive Substack essay that he links to here, Three Kinds of Theology: The Poetic, The Philosophic, and The Political, he quotes the great historian of philosophy Frederick Copleston on the position of Panaetius and his fellow Stoics: “The theology of the poets,” he says, “is anthropomorphic and false.” “The theology of the philosophers,” on the other hand, “is rational and true, but unfitted for popular use.” “The theology of the statesmen,” however, is valuable because it “maintains the traditional cult and is indispensable for public education.”

Today, as we saw in yesterday’s post, social scientists are rediscovering the social and psychological benefits of religion. Progressive Christians have long been preaching a “social gospel” of the left. Now, many conservative Christians are preaching a “social gospel” of the right. We might see the “prosperity gospel” of many Pentecostals as a variation of that.

Again, Christianity can have a “political” mode in the sense of a social conscience, one which opposes the evils of society, such as abortion and other kinds of child abuse. And in their vocations as citizens in the civil estate, they can take political action against such injustices. But the “political” must not displace the personal salvation offered by God’s Word (Panaetius’s term “poetic” is too weak of a term for this), nor the truths of Christian doctrine (“theological” is a better term than “philosophic”).

In fact, we might say that truth is what can tie all of these modes together for Christians: God’s Word is not just a collection of psychologically helpful stories as Jordan Peterson sometimes reduces them to; rather, God’s Word is true. Christian theology is not just metaphysical speculation or reasoning about abstractions; rather, insofar as it is based on God’s Word, theology is true. Christian social influence is not about acquiring political power or social prestige; rather, Christian social influence grows out of the truth of God’s Word and the truth of Christian theology, which reveals transcendent moral absolutes that are true.

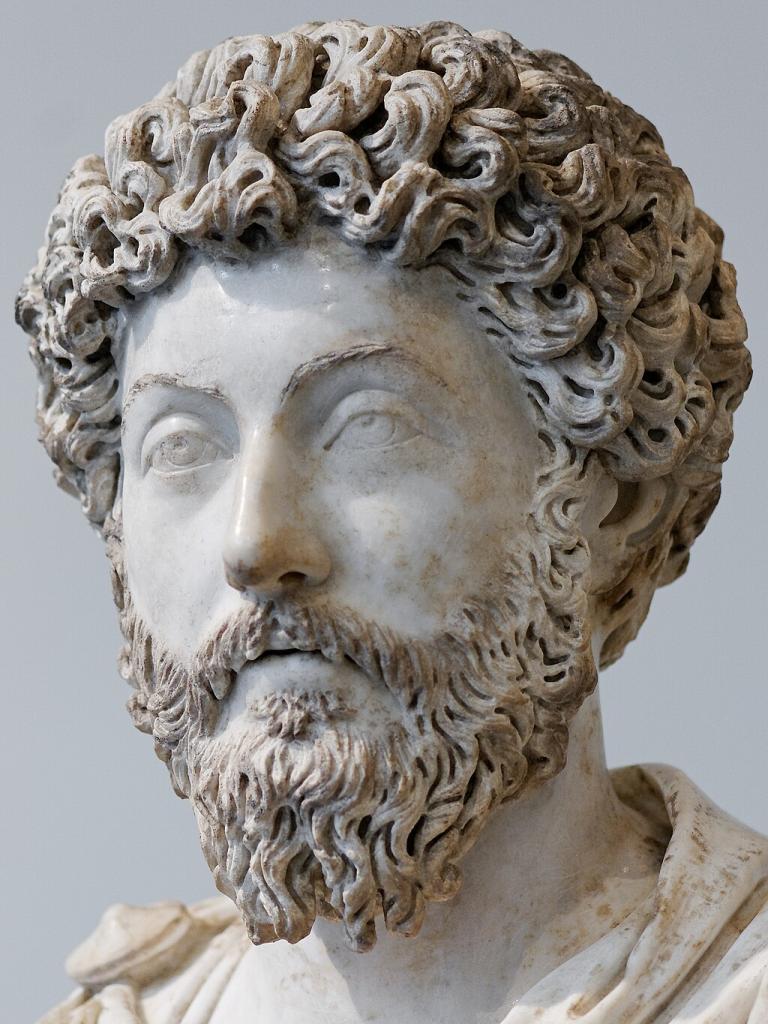

But if are seeing a revival of Stoicism, as our post on the subject suggested, a religion in the “political” mode may be in our future. Just remember that the last time Stoicism was in vogue, in ancient Rome, its vaunted religious toleration, since it required belief in no particular god, did not extend to Christians. That is because Christians refused to take part in “the traditional cult” of the civil religion. Not burning the incense to Caesar was a rejection of the one dimension of religion that the Stoics thought was important. Remember too that the great Stoic sage, the emperor Marcus Aurelius, author of the still-popular Meditations, presided over one of the most intense periods of Christian persecution for this very reason.

Photo: Bust of Marcus Aurelius (ca. 161–169 A.D.), Louvre Museum, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons