Christians often have trouble dealing with grief. Think of the trouble non-Christians must have!

Lutheran theologian Oswald Bayer has written about secular theodicy, pointing out that concluding that God must not exist does not solve the problem of theodicy–why would a just, omnipotent God allow bad things to happen?–but, rather, makes it worse.

Why does existence include all the bad things that happen? Without the resources of theology, observes Bayer, there can be no answer to that at all. How can existence be anything else than meaningless? How can life be worth living?

With all the pain and evil in the world, how can existence without God be good?

I randomly stumbled across an article at Big Think by that site’s philosophy columnist Jonny Thomson entitled Three responses to grief in the philosophy of Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and Camus with the deck, “How we handle grief largely depends on our worldview. Here is how three famous philosophers handled the certainty of grief and despair.”

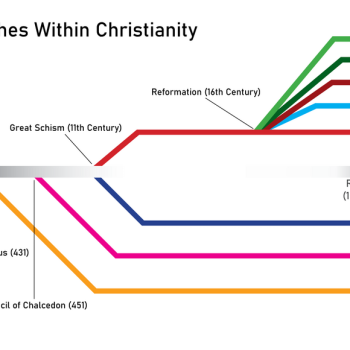

Each of these three thinkers are in the existentialist camp, but while two were atheists, one was a Christian, indeed, a Lutheran, though not completely orthodox. But we can see in them the contours of “secular theodicy” and the difference that the Christian faith makes possible.

First, Heidegger:

The German phenomenologist Martin Heidegger argued that the presence of death in our lives gives fresh meaning to our being free to choose. When we appreciate that our decisions are all we have, and that our entire life is punctuated by a final coup de grace, it invigorates our action and gives us a “daring.” As he wrote, “Being present is grounded in the turning-towards [death].” It is a theme echoed in the medieval idea of memento mori — that is, keeping death close to make the current moment sweeter. When we lose a loved one, we recognize that we are, indeed, left behind, and so this in turn gives new gravity to our choices.

Here is the attempt to make the will the source of all meaning. “Our being free to choose” has become the hallmark of today’s postmodernism and nearly all of its issues (abortion, sex, transgenderism, psychology, politics, religion, etc.). Here too is the notion that the transience of life makes the moment “sweeter,” a common theme in Romantic poetry and Japanese aesthetics.

But the final result just loops in on itself. The loss of a loved one “gives new gravity to our choices”? What does that mean? We are left, again, with an invocation of choice. But surely grief–like disease, death, and all other obstacles and disappointments–is not chosen. These are realities that go beyond what we are “free to choose,” truths that are not relative, that we did not “construct” for ourselves. Secular theodicy is precisely about what we do not choose. So a philosophy built around “choice” does not do us much good.

Second, we have Camus:

For Albert Camus, though, things are somewhat more bleak. Even though Camus’ works were a deliberate and strenuous effort to resolve the listless abyss of nihilism, his solution of “absurdity” is not easy medicine. For Camus, grief is a state of being overcome by the pointlessness of it all. Why love, if love ends in such pain? Why build great projects, when all will be dust? With grief comes an awareness of the bitter finality of everything, and it comes with an angry, screaming frustration: Why are we here at all? Camus’ suggestion is a kind of macabre revelry — gallows’ humor perhaps — that says we should enjoy the ride for the meaningless rollercoaster it is.

But grief is precisely what we cannot enjoy. To say life is absurd so we should be absurd doesn’t help. Camus basically admits that there is no answer to secular theodicy, so we might as well just give up.

Here is Kierkegaard:

For Søren Kierkegaard, that visceral sense of mortality we get after experiencing grief he labelled “despair.” And in the long nighttime of despair, we can begin the journey to realize our truest selves. When we meaningfully encounter first-hand that things in life are not eternal and nothing is forever, we appreciate how we passionately long for things to be eternal. The source of our despair is that we want that “forever.” For Kierkegaard, the only way to overcome despair, to relieve this condition, is to surrender. There is an eternal by which to lose ourselves in. There is faith, and grief is the dark, marble door to belief.

I love that metaphor: grief as “the dark, marble door” that leads to belief. We get a glimpse of law, which does bring realization of death, and gospel, which is a kind of surrender.

I know the objection from skeptics: Longing for something doesn’t make it real. And, yet, if we long for something, we must have a conception of it, and where does that conception come from? What does it point to? C. S. Lewis wrote perceptively about longing as a signpost to Christian reality (see this, this, and Lewis’s memoir Surprised by Joy).

And I know the objection from believers: Kierkegaard here doesn’t attend to the object of the law, namely, sin, or to the object of faith, namely, Christ. But in The Sickness Unto Death, which Thomson is taking this from, he does talk specifically about sin and about forgiveness through Christ. For example, here Kierkegaard deals pretty deftly with two kinds of unbelief:

Now comes a self face to face with Christ — a self which nevertheless in despair will not be itself, or in despair will be itself. For despair of the forgiveness of sins must be related to one or the other formula of despair; that of weakness, or that of defiance; that of weakness which being offended does not dare to believe, or that of defiance which being offended will not believe.

Even non-believers, whether weak or defiant, long for something transcendent, if not for eternity (Kierkegaard’s “forever”), for a life that is “good,” without the griefs that call the goodness into question. But there can be no answer to a secular theodicy. For that, however hard it may be to understand, we must keep the theos in theodicy.

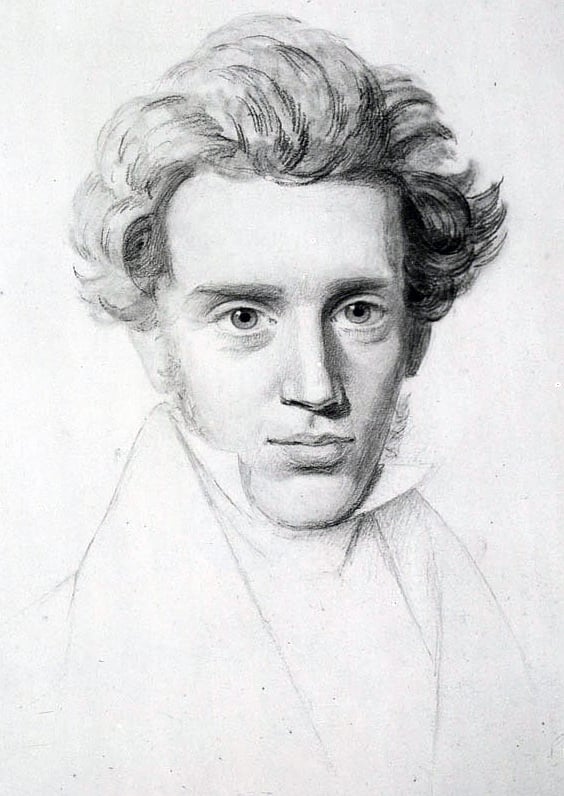

Illustration: Søren Kierkegaard (c. 1840), sketch by his cousin Niels Christian Kierkegaard, Royal Library, Copenhagen via https://www.flickr.com/photos/45270502@N06/9645352916/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78022219