Last week we blogged about Liberal Theology & Eugenics, saying that the attempt to breed genetically superior humans and to eliminate the unfit from the gene pool “is repellent to just about everyone today.”

Well, that is not quite true. The concept seems to be coming back into vogue, especially among Silicon Valley tech lords who like to think of themselves as constituting a more highly evolved master race.

Unlike a growing percentage of regular Americans, these men and women do want to reproduce. After all, Darwin teaches that animals that are most successful in transmitting their genes to the most progeny are the evolutionary winners. But instead of going about it in the ordinary way of marriage and parenthood, many in the tech world want to direct the process themselves, using technology.

The Washington Post has published an article by Elizabeth Dwoskin and Yeganeh Torbati entitled Inside the Silicon Valley push to breed super-babies. It tells about a number of tech start ups devoted to the genetic screening and implantation of embryos. The would-be parents donate their eggs and sperm, from which the company generates a large number of embryos. Then cells from each embryo are subjected to genetic analysis, with attention to their genetic traits and susceptibility to various diseases. Then the parents decide which of the embryos has the genetic makeup they want. The chosen one is implanted into either the female client or a surrogate mother, whereupon the “super baby” is allowed to be born. The others are disposed of or frozen.

The story focuses on one 30-year-old entrepreneur named Noor Siddiqui, who started a company called Orchid.

Orchid is the first company to say it can sequence an embryo’s entire genome of 3 billion base pairs. It uses as few as five cells from an embryo to test for more than 1,200 of these uncommon single-gene-derived, or monogenic, conditions. The company also applies custom-built algorithms to produce what are known as polygenic risk scores, which are designed to measure a future child’s genetic propensity for developing complex ailments later in life, such as bipolar disorder, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, obesity and schizophrenia.

Other IVF clinics screen for “monogenic” conditions–that is, disorders directly caused by one specific gene configuration–but Orchid will provide statistical chances for “polygenic” conditions, which are caused by multiple factors. Most geneticists are skeptical that this can be done, and they question Orchid’s claim to be able to sequence an embryo’s entire genome based on only five cells.

But Orchid has lots of clients and is making lots of money, charging $20,000 for each IVF cycle, plus $2,500 for every embryo screening.

Most couples use In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)–that is, fertilizing the egg “in a glass,” rather than inside a body–to address problems with conception. But Orchid and similar clinics are doing it for eugenic reasons.

Siddiqui, says the article, “advocates a bolder idea gaining ground in the tech world: that increasingly available and sophisticated fertility technologies will supplant sex as a preferred method of reproduction for everyone.”

As she says in a video, “Sex is for fun, and embryo screening is for babies.”

Thus, separating sex completely from reproduction will free sex even more, while giving over reproduction completely to eugenics.

Siddiqui says that Orchid is not eugenic, that it counsels clients not to throw away unwanted embryos, and that it does not select for traits such as intelligence.

A growing number of start-ups do, however. One of them is the Thiel-funded start-up Nucleus; another is Heliospect Genomics, the research arm of Herasight, an executive of which is a bioethicist who advocates “liberal eugenics” — casting that term as applying not to governmental efforts to weed out undesirable births but instead to parents’ use of emerging biological tools to enhance their children’s prospects.

Until last month, Orchid’s website featured advice from that bioethicist, Jonathan Anomaly, on overcoming skepticism about its service. “We intentionally alter our environments, breed crops so that they’re more nutritious and easier to harvest, and we’ve invented lightning rods and vaccines to make us less likely to die from natural disasters,” he wrote. “I find the playing God objection a bit tiresome.” Orchid removed the page after The Post asked about it. Anomaly said he now prefers the term “genetic enhancement” to “eugenics.”

The article describes a couple that used Orchid’s services, showing the kind of decisions that may become the norm if embryo screening supplants natural childbirth. The couple was worried because they both carried a gene that could produce hearing loss. So instead of just having to decide on what to name the baby, they had to decide on which baby they would let survive:

George and Kang produced 12 embryos and used Orchid to screen all of them — a cost of $30,000 on top of IVF. Six were viable. Two had the hearing loss gene variant. Another two were carriers, which meant they could pass the gene on to their children but wouldn’t be affected themselves. And two, called embryos JK3 and 6-JK in Orchid’s report, were unaffected.

The couple pored over their spreadsheets, debating which of the two to select. One embryo had a 1.5 percent lifetime risk of bipolar disorder, about half that of the general population. But its type 2 diabetes risk — 29 percent — was slightly above average, about 1.2 times that of a typical person. Another had a slightly higher risk of obesity. . . .After weighing all the other factors, the polygenic scoring became “the tiebreaker,” George said. Kang gave birth in March; so far, their daughter, Astra Meridian, has perfect hearing.

They didn’t want a deaf child, with all that sign language bother. And they didn’t want a diabetic, all of that blood work and having to avoid sugar, even though the child would likely be more stable mentally than usual. And they certainly didn’t want obesity in a child of theirs! Who wants a fat baby?

So they have their super-baby. They are probably trying not to think about their other eleven babies who were not so super.

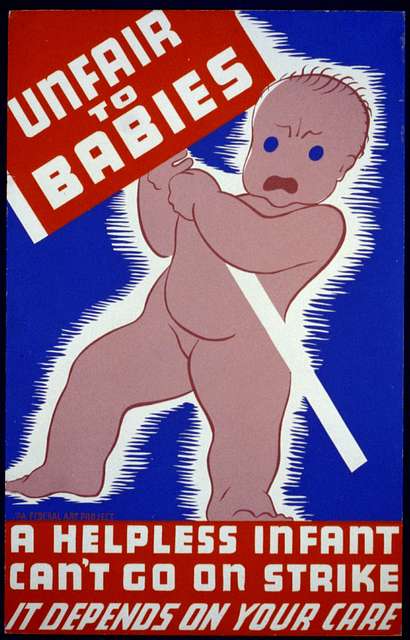

Illustration: Work Projects Administration Poster Collection (1930), Library of Congress, via GetArchive, Public Domain.