President Biden has commuted the sentences of some 1,500 prisoners and issued full pardons to 39. In her article on the subject, AP reporter Colleen Long says that this is “the largest single-day act of clemency in modern history.”

Not only that, President Biden is considering issuing pardons to people who haven’t even been charged with a crime. These are the officials who are afraid that the new President Trump will do unto them what they tried to do unto him, using the law to punish a political opponent.

Commuting a sentence ends the punishment, though the conviction stands. The 1,500 beneficiaries had been moved out of prisons to home confinement due to COVID epidemic efforts to ease overcrowded conditions. The 39 full pardons, which both ends punishment and erases the conviction, each has its own story. The White House said that those who had been pardoned were found guilty of non-violent crimes such as drug offenses, fraud, or theft, but have turned their lives around. (Reports that the pardons included two Chinese spies and the relative of a Chinese communist official caught with child porn confused this action with last month’s prisoner-swap for three Americans.)

But is it possible to pardon someone who hasn’t been convicted of anything? In a 1915 Supreme Court decision, Burdick v. United States, regarding whether a person could refuse a pardon, the justices said that a pardon carries with it “an imputation of guilt and acceptance of a confession of it.” President Woodrow Wilson issued a blanket pardon to prevent two newspaper editors who refused to name names in a bribery case from invoking the Fifth Amendment. He reasoned that if they were protected from prosecution, they would have no recourse to their constitutional right protecting them from self-incrimination and so could be forced to testify. The court ruled that they could refuse the pardon as a way to maintain their innocence and keep their constitutional protections. However, the ruling in Burdick also established that presidential pardons do not require a conviction or even an indictment. President Ford invoked this provision when he pardoned Richard Nixon, who had not yet been indicted or convicted. So it would seem that President Biden could pardon officials not charged with a crime, though accepting the pardon would come with a presumption of guilt.

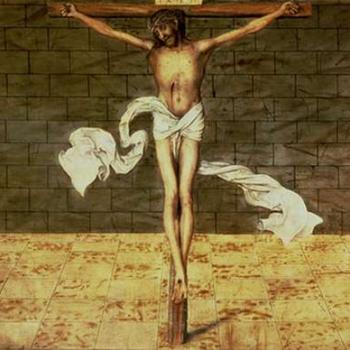

In our earlier post, Presidential Pardons vs. God’s Pardons, we discussed President Biden’s pardon of his son Hunter for any crimes “which he has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 1, 2014, through December 1, 2024.” We pointed out that presidents pardon crimes simply by decree, whereas God pardons by atoning for the transgression.

The possibility of pardoning someone who is presumed innocent brings up another important difference. When we receive God’s pardon, we do confess our guilt. I love the emphatic and thorough taking of responsibility expressed in the rite of confession in the service of Compline: “I have sinned in thought, word, and deed by my fault, by my own fault, by my own most grievous fault.” This is repentance.

When we hear God’s Law and realize, deep down, that we have violated it, that, in the words of confession in the Divine Service, “I. . . justly deserved Your temporal and eternal punishment,” we know our need for Christ, whereupon we gladly seize upon the promises of the Gospel, that “there is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1). In doing so, we “are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith” (Romans 3:24-25).

Today, though, churches often leave out the part about the Law and repentance, thinking that the Gospel is just like President Biden issuing pardons.

The progressive theology of mainline Protestantism thinks the Gospel is like President Biden issuing pardons for people who aren’t guilty of anything. They try to convince homosexuals, committers of abortion, and the like that what they are doing is not a sin, but rather a good thing to be affirmed. If this is true, why do they need the pardon of Christ in the Gospel? How could they receive it? Are they to be repentant for other sins, such as losing their temper or being judgmental, just not their sexually-related sins?

Isn’t it better for churches to teach and for us to acknowledge that we are all sinners in every part of our being, that we are not at all righteous, so that we can know the fullness of God’s grace and the scope of Christ’s sacrifice for us (Romans 3)?

Illustration: Pardon974, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons