Is religion, so beat up by secularism in recent years, on the verge of a comeback?

He begins by pointing out that the New Atheist phenomenon, which was so popular on best-seller lists and online a decade or two ago, was a product of its time. Fear of religious fundamentalism after 9/11, the Catholic sexual abuse scandals, and the iconoclastic spirit of the internet all contributed to a widespread reaction against religious belief.

But all of that feels anachronistic today. Scientific rationalism has not solved our problems. Humanism has not made us more humane. Instead, says Douthat, we have “existential anxiety and civilizational ennui.” People are plagued by mental problems, lack of community, an absence of meaning in their lives. And researchers have connected that malaise to a lack of religion. Meanwhile, the “Nones” are turning not to the chilly certainties of reason alone, as the New Atheists hoped, but to psychics, psychedelic drugs, astrology, UFOs, and other New Age spiritualities that by any measure are far less rational than Christianity.

Today a number of former secularists have converted to Christianity. Even some of the New Atheists have changed their tune. Richard Dawkins still doesn’t believe the doctrines, but he now considers himself a “cultural Christian.” And Ayaan Hirsi Ali, whom Dawkins once hailed as the “horsewoman” of the New Atheism has gone all the way and now embraces Christianity.

Douthat says the world seems “primed for religious arguments,” not just that religion is culturally valuable but that it is true. He himself , a Catholic convert, says that he has a book on that subject coming out next year. But he focuses on three other recently published books that he thinks could be game changers, “covering the philosophical, the scientific and the experiential cases for a religious perspective on the world.” Let’s call them New Theists. (Douthat doesn’t use the term, but we might as well. Though it’s been used before.)

For the philosophical, he refers to the American Orthodox thinker David Bentley Hart‘s new book All Things Are Full of Gods: The Mystery of Mind and Life. It’s a series of Platonic dialogues between ancient Greek deities who meet to discuss the mysteries of consciousness, existence, and mind. In doing so, in the words of the editorial description at Amazon,

He systematically subjects the mechanical view of nature that has prevailed in Western culture for four centuries to dialectical interrogation. He argues through the gods’ exchanges that the foundation of all reality is spiritual or mental rather than material. The structures of mind, organic life, and even language attest to an infinite act of intelligence in all things that we may as well call God.

Engaging contemporary debates on the philosophy of mind, free will, revolutions in physics and biology, the history of science, computational models of mind, artificial intelligence, information theory, linguistics, cultural disenchantment, and the metaphysics of nature, Hart calls listeners back to an enchanted world in which nature is the residence of mysterious and vital intelligences. He suggests that there is a very special wisdom to be gained when we, in Psyche’s words, “devote more time to the contemplation of living things and less to the fabrication of machines.”

Douthat comments that the dialogue form allows Hart to let opposing views make their strongest case, and yet his notion that mind–and thus spirit, and thus God–underlies physical existence is very persuasive.

Addressing the scientific is Spencer Klavan’s Light of the Mind, Light of the World: Illuminating Science Through Faith. Klavan does something in this book that is long overdue; namely, thinking through the implications of quantum physics for our view of reality.

The post-Enlightenment view of science, premised on rationalistic materialism, assumes that nature consists solely of physical elements interacting with each other in accord with natural laws discernible by reason. But this materialistic order has been disrupted by quantum physics, which shows scientifically, that underlying nature and its laws are mind-boggling quantum phenomena that defy the simplistic reductionism of human reason. From Amazon’s editorial review:

Surveying the history of science and faith from the astronomers of Babylon to the quantum physicists of postwar Europe and America, classicist and scholar Spencer A. Klavan argues that science itself is leading us not away from God but back to him, and to the ancient faith that places the human soul at the center of the universe. Reconciling the discoveries of science with the truths of the Bible, Klavan shows how the search for knowledge of the natural world can help illuminate the glories of its Creator, and how the latest developments in physics can help shatter the illusion of materialism.

Douthat is taken especially by Klavan’s point that, according to the findings of quantum physics, “probabilities only collapse into reality itself when a conscious mind is there is to measure and observe.” Therefore, says Douthat, we must “accept that there is only one reality and that it’s ‘created when consciousness gives shape to time and space’ — created in some sense every time we look upon it, and created fundamentally by the Power that said let there be light in the first place.”

In other words, if there is any kind of objective reality, there must be an Observer. Not only to create reality at the very beginning, as the Deists thought, but also to keep it in existence at every moment, the richer teaching of Christianity.

I first heard this articulated by a reader and sometimes commenter on my blog, my cousin by marriage, the pioneering engineer Bob Foote: That quantum physics requires a transcendent Observer, whom we know as God.

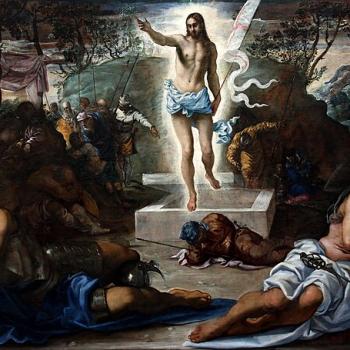

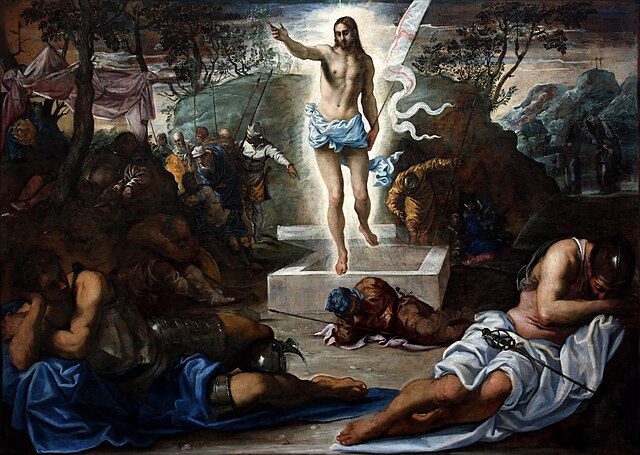

Addressing the experiential is Rod Dreher’s Living in Wonder: Finding Mystery and Meaning in a Secular Age. His point is that the supernatural breaks in upon us all the time! From Amazon’s editorial review:

In his trademark mixture of analysis, reporting, and personal story, Dreher brings together history, cultural anthropology, neuroscience, and the ancient Church to show you–no matter your religious affiliation–how to reconnect with the natural world and the Great Tradition of Christianity so you can relate to the world with more depth and connection.

He shares stories of miracles, rumors of angels, and outbreaks of awe to offer hope, as well as a guide for discerning and defending the truth in a confusing and spiritually dark culture, full of contemporary spiritual deceptions and tempting counterfeit spiritualities.

The world is not what we think it is. It is far more mysterious, exciting, connected, and adventurous. As you learn practical ways to regain a sense of wonder and awaken your sense of God’s presence–through prayer, attention, and living by spiritual disciplines–your eyes will be opened, and you will find the very thing every one of us searches for: our ultimate meaning.

I would add to Douthat’s list of books Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World by historian Tom Holland, who shows that the beneficent values people prize today–mercy, equality, kindness, peace, the value of each person, rights, freedom, etc.–cannot be found in Greco-Roman paganism and emerged from Christianity and nowhere else. This one adds to “the philosophical, the scientific and the experiential cases,” the historical case.

We’ve blogged about Dominion already, so go to that post. The main argument of the New Atheists was that Christianity is bad, that it has had a baleful, repressive influence on Western culture. Holland’s book utterly refutes that claim and is reportedly a factor in the conversion of Ayaan Hirsi Ali.

I haven’t read Douthat’s three books yet, but I plan to. (I put them on my Christmas list!) I am working on Holland’s. Have you read any of these? If so, please report about them in the comments.

Photo: David Bentley Hart by Jjhake, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons